What Is an Entity in Slate

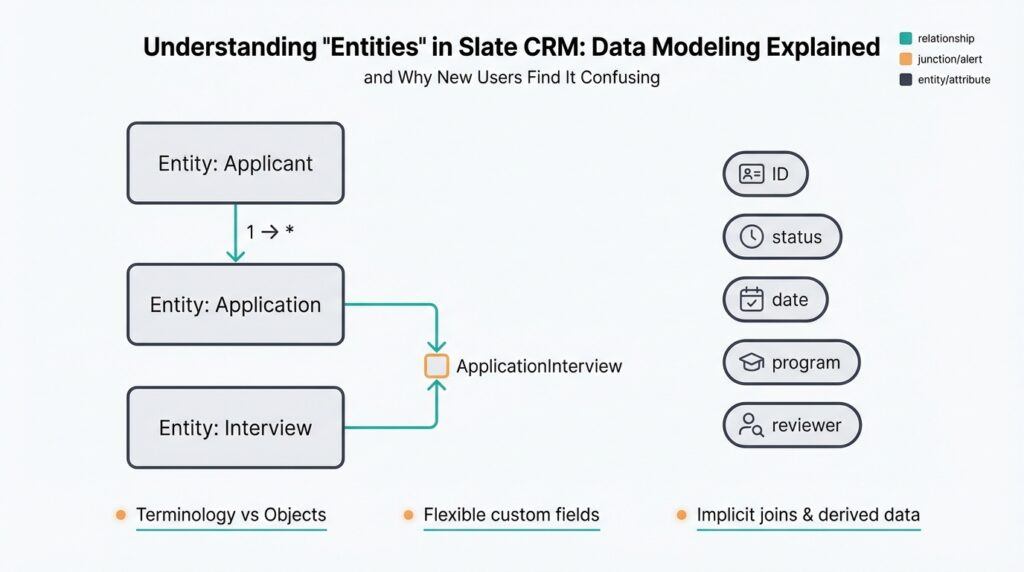

Building on this foundation, think of a Slate entity as the canonical schema unit that represents a thing you care about inside Slate CRM—the object type you query, report on, and run workflows against. An entity in Slate is not merely a form or a list; it’s the structural definition that bundles fields, validation rules, and relationships into a reusable model. Why does this matter? Because when you design your Slate data model, getting entity boundaries right determines how easy it will be to query records, join related information, and automate downstream processes.

At a technical level, a Slate entity corresponds to a logical record type—akin to a database table or an ORM class—but conceptually richer because it carries behavior (validation, triggers) and metadata for the CRM UI. You can think of entities as typed containers: they expose named fields (attributes), enforce data constraints, and let you attach actions like data transformations or notifications. Practically, that means when you create an Applicant entity you’re defining the set of attributes, rules, and relationships that every applicant record will inherit across Slate CRM workflows and reports.

It helps to contrast entities with related artifacts to avoid confusion. Forms and pages are user-facing surfaces that collect or display data, while fields are the atomic values; the entity is the schema that organizes those fields into a coherent model. For example, instead of stuffing application-specific fields into a generic person record, you’d create a separate Application entity to hold program-specific answers and submission metadata. This separation keeps your data normalized, reduces duplication, and simplifies queries when you need to filter or aggregate by application-specific criteria.

Relationships are where entities reveal their real power. Entities connect via one-to-many or many-to-many relationships, and you should model those explicitly rather than embedding data redundantly. For instance, an Applicant entity will typically have a one-to-many relationship to an Application entity (one person, many submissions), while an Application might link to a Program entity as a many-to-one. When many-to-many relationships are required—say applicants can be associated with multiple events—you model that with a join entity (a relational table equivalent) so you can attach attributes to the association itself, like attendance status or registration timestamp.

Entities also drive automation, reporting, and permissioning inside Slate CRM. Because workflows and merge fields reference entities and their fields, clear entity models let you write dependable queries, trigger targeted communications, and build reliable reports. For example, if we normalize test scores into a TestResult entity instead of mixing them into the Applicant object, we can run cohort analyses across programs without complex parsing or brittle string matching. This separation also makes it easier to implement access controls—restricting who sees what—at the entity or field level rather than juggling ad-hoc filters.

When you map existing systems into Slate, treat entity design as a migration first-class concern rather than an afterthought. Identify bounded contexts (what belongs to admissions versus outreach), avoid creating an entity for every nuance of a legacy spreadsheet, and consider whether to normalize or denormalize based on query patterns and reporting needs. Start with a few canonical entities, migrate a representative sample of records to validate relationships, and iterate; taking this concept further, your next step is to translate those entity boundaries into concrete data flows and import pipelines so downstream automations behave predictably.

Entity Scopes: Person Application Dataset

Building on this foundation, the most common source of confusion is scope: which attributes belong to the person record, which belong to the application record, and when a separate dataset or join entity is the right choice. We see this confusion repeatedly when teams map legacy spreadsheets into Slate CRM and collapse multiple concerns into a single entity. Clarifying scopes early prevents brittle queries, confusing automations, and sprawling imports—and it makes permissioning and reporting predictable as you scale.

The guiding question you should ask for every field is simple: what is the natural lifecycle and cardinality of this value? If a value lives with an individual across every interaction and doesn’t change per submission, it belongs on the person-level entity; if it is specific to a submission—answers, status, submitted_at—it belongs to the application-level entity; if the item represents many-to-many or repeated measurements (test scores, event attendance), model it as a dataset or join entity. This rule of thumb—lifecycle, multiplicity, and ownership—lets you decide where data should live without guessing.

Consider concrete examples to make the decision practical. Store name, primary email, legal identifiers, and long-lived demographic attributes on the person entity because they describe the individual irrespective of program. Put essays, program-specific question answers, recommender uploads, and application.status on the application entity because each submission can differ per program and per term. For repeated measurements—SAT scores, interview slots, or event RSVPs—create a separate dataset or result entity so you can attach metadata (score_type, test_date, source) and preserve a clean one-to-many relationship between person and those records.

When you implement this, model the tables and indexes explicitly so queries stay performant. For example, define Person(id PK, name, email, dob) and Application(id PK, person_id FK, program_id, submitted_at, status). Index application(person_id, submitted_at DESC) to retrieve the latest submission per person quickly. For a dataset-like TestResult(id PK, person_id FK, test_type, score, test_date, source) use a composite index on (person_id, test_date). In import pipelines, perform person dedupe first, then import application rows referencing resolved person_id; for delta loads, update application.status by matching external_submission_id to application.id rather than re-merging person-level fields.

Reporting and automation depend on picking the right scope up front. When you build a cohort report about yield by program, aggregate at the application-level dataset (group by program_id), not the person record, to avoid double-counting applicants with multiple submissions. When triggering emails, reference the application entity for submission-specific messages and the person entity for ongoing relationship outreach. From a security standpoint, limit access to application fields that contain sensitive review data, and expose basic person fields more broadly; this keeps permissioning aligned with both privacy requirements and Slate CRM workflows.

If you apply these scope rules consistently, your model will support predictable joins, maintainable automations, and accurate reporting—so the next practical step is translating those scopes into import specifications and relationship diagrams we can validate with sample data. In the following section we’ll take those diagrams and convert them into concrete import templates and test queries that prove the model behaves as expected.

When to Use Entities Versus Fields

Choosing between adding a field and modeling a full Slate entity is one of the most consequential decisions you make in Slate CRM data modeling, and it often determines how maintainable and queryable your system will be. We frequently see teams default to fields because they’re fast to create, but that impulse creates technical debt when values are multi-valued, audited, or need independent lifecycle rules. How do you decide whether a value belongs as a field or as its own typed container? Use the lenses of cardinality, lifecycle, query patterns, and automation to make a principled choice.

Start with cardinality and ownership. If a value is single-valued, stable across sessions, and owned by the person-level concept, a field on the person entity is appropriate. If a value can repeat, evolve over time, or belongs to an interaction (a submission, an event, a test), model it as a separate entity so you preserve one-to-many semantics and avoid overwriting history. For example, one phone number that rarely changes fits as a phone field; multiple contact attempts, each with a timestamp and outcome, belong in a ContactAttempt entity like ContactAttempt(id, person_id, attempt_at, channel, outcome).

Consider reporting and performance next. If you plan to filter, aggregate, or join on the value frequently—say calculating trends, cohort membership, or the latest measurement—an entity with its own indexes will perform far better than a JSON blob or repeated fields on a parent record. Denormalize only when query patterns demand read-optimized tables; denormalization (storing a computed summary on the parent record) trades write complexity for faster reads, but you should document and automate the reconciliation logic to avoid drift. Ask: will reports need to group by this attribute, or will we only show it on a single record view? If the former, prefer an entity.

Automation, permissions, and UX drive another set of trade-offs. Workflows, triggers, and merge fields in Slate CRM reference entities and their fields; if you need to attach status, files, or approval metadata to the value, an entity lets you attach those behaviors directly. Similarly, if the value contains sensitive review data you want to gate separately from general person information, put it in an application- or dataset-level entity and scope permissions accordingly. If a value is used only to prefill forms or display non-sensitive labels, keeping it as a simple field reduces complexity and keeps UI flows straightforward.

Practical implementation matters: imports, deduplication, and data migrations shape your operational cost. When migrating from spreadsheets or legacy systems, prototype with a representative sample and validate joins before mass-importing. Import person records first (resolve dedupe), then import dependent entity rows referencing resolved person IDs. If you need to migrate a field into an entity later, backfill the new entity table from the existing field and update downstream automations to reference the entity ID—this preserves historical data and minimizes downtime. Monitor import performance and add composite indexes that match your most common query predicates.

Use a simple checklist when you design: does the value repeat? Does it change over time independently? Will we query or aggregate it often? Does it require separate permissions, attachments, or workflow logic? If you answered “yes” to one or more, model a Slate entity; otherwise, favor a field for simplicity. Taking this approach ensures our data model remains predictable for reporting, efficient for queries, and flexible for automation—so next we can translate these boundaries into import templates and test queries that prove the model behaves as intended.

Creating Entities: Fields and Structure

When you start designing data structures in Slate CRM, the hardest choices are rarely technical—they’re about ownership and shape. We see teams create dozens of fields on a single record because fields feel fast, but that impulse produces brittle automations and confusing reports. Right away, decide whether a value is a property of the person, the submission, or the association between two objects; that decision will dictate the fields you create and the relationships you model. Getting this right up front saves hours of rework during imports, dedupe, and downstream workflows.

Begin by treating a field as an atomic attribute with three explicit properties: type, cardinality, and lifecycle. Define type (string, integer, date, boolean, file, picklist) and enforce validation rules so you don’t end up with free-text garbage that breaks joins later. For cardinality, mark whether a field is single-valued or multi-valued at design time; if you need repeated measurements (scores, RSVPs), model those as a separate entity rather than a repeated field. How do you decide which fields belong on the person record versus an application record? Use lifecycle: if the value changes per submission, it belongs to the submission-scoped model.

Field behavior matters beyond storage. Configure defaults, requiredness, and computed fields where appropriate so workflows and reporting can rely on consistent values. Use picklists for values you will aggregate or filter by—status, decision, cohort—and prefer normalized keys to human labels so JOINs and automations remain stable when labels change. For sensitive or binary assets (recommendation letters, transcripts) use file-typed fields linked to a dataset entity that records provenance, upload_time, and access controls. We recommend naming conventions such as snake_case for field names and suffixes like _at for timestamps (submitted_at, reviewed_at) to make intent obvious in queries.

Structure your relationships deliberately instead of embedding arrays or JSON blobs on parent records. Where many-to-many semantics exist—applicants attending events, applicants tied to multiple programs—introduce a join entity that can carry attributes of the relationship (attendance_status, registered_at, checked_in_by). When you need repeated measurements, model a result or event dataset (TestResult, ContactAttempt) with foreign keys back to person and application; this preserves history and enables efficient aggregation. Index join columns you query frequently (person_id, application_id) and add composite indexes for common predicates (person_id, test_date DESC) so retrieving latest rows is fast.

Operational concerns shape field and structure decisions. During imports, resolve person dedupe first and import dependent rows referencing resolved IDs; avoid importing denormalized person data repeatedly into submission records. Add audit fields (created_by, created_at, source_system) to every major object so we can trace origins during reconciliation and backfills. If you plan to denormalize for performance, codify the reconciliation process: which fields are canonical, which are derived, and how to rebuild summaries from raw datasets. These choices affect permissions as well—place sensitive review fields inside submission-scoped objects so access can be restricted independently of the person record.

Taking a principled approach to fields and structure turns Slate CRM models from ad hoc spreadsheets into reliable schemas you can query, report, and automate against. We’ll use these conventions when we translate the model into import templates and test queries, validating joins and index choices with sample data before a full migration.

Displaying Entities On Records and Tabs

Building on this foundation, the way you surface a Slate entity on person records and in tabs determines whether users find the system useful or confusing. Slate entity, records, tabs and Slate CRM UI are the terms we use to decide what appears on the primary record versus what lives behind a click. How do you decide whether to surface an entity on the person record or in a tab? That question guides both data-model trade-offs and UX choices you’ll make during implementation.

Start by aligning display decisions with cardinality and lifecycle rather than aesthetics. If a value is one-per-person and frequently referenced—primary email, current status, or an aggregated score—display it directly on the record so users don’t need extra navigation. If rows are many, time-ordered, or require workflow actions—application submissions, test results, event RSVPs—expose them in a related-data tab. This keeps the record focused, reduces cognitive load, and preserves click-through paths for deeper work.

For practical implementation, use summary fields and targeted queries to bridge the gap between inline display and tabbed detail. Create computed fields or denormalized columns on the person entity that store the latest or aggregated value (for example, latest_application_status or sat_latest_score) and keep that data synced by triggers or scheduled jobs. When you do need the full history, query the related entity: SELECT * FROM Application WHERE person_id = ? ORDER BY submitted_at DESC LIMIT 50. That pattern gives you fast, searchable summaries on records and efficient, paginated lists inside tabs.

Tabs should be treated as first-class UI queries, not static dumps of rows. Configure each tab as a filtered view of its entity with sensible defaults for sorting, column selection, and row actions (open, attach file, trigger review workflow). For example, an Applications tab might default to show active program_id and submitted_at, allow reviewer assignment inline, and expose bulk actions that run against the Application entity. Also scope tabs to permissions—restrict sensitive review fields at the tab level so reviewers see only what they need to act on.

Performance considerations change display decisions. Don’t eager-load multi-thousand-row datasets into the main record load; lazy-load tabs or show lightweight counts (application_count) and a two-line preview that links to the full tab. Maintain composite indexes that match the tab’s common filters (person_id, submitted_at DESC) to make tab queries responsive. If you denormalize summaries onto the person record, document reconciliation logic and use idempotent background jobs to recalc aggregates during imports and backfills.

From a UX and operations perspective, prioritize clarity and consistency. Surface only the most actionable entity fields on the record header and use consistent naming for tab titles and column labels across different record types. Visual cues—badges for decision_status, color for urgency, or icons for attachments—help you scan records quickly without opening tabs. For auditing and troubleshooting, include source_system and updated_at on both summaries and tab rows so we can trace where a displayed value originated during a migration or sync.

Taking these patterns together lets you design a display strategy that respects your Slate CRM model while giving users immediate, actionable context. Next, we’ll map these display choices into concrete import templates, computed-field implementations, and test queries that prove the person-level summaries and tabbed entity lists behave correctly under real data volumes.

Querying, Merge Fields, And Exports

Building on this foundation, the most common operational friction you’ll hit in Slate CRM is a mismatch between how you query entities, how you render merge fields, and how you produce exports. When those three concerns aren’t aligned you get wrong personalization in emails, double-counted rows in analytics, and expensive exports that time out. Front-load your design conversations with the words query, merge fields, and exports so these outputs are requirements—not afterthoughts—of your entity model and import templates.

Start with queries because they define the shape of everything downstream. A query should always be written against the canonical entity model we designed earlier: join Person to Application by person_id, join TestResult by person_id and test_date, and filter by indexed predicates (for example submitted_at). For example, express intent with a pseudo-SQL query like SELECT p.id, p.email, a.id AS application_id, a.program_id, a.status FROM Person p JOIN Application a ON a.person_id = p.id WHERE a.submitted_at BETWEEN ‘2025-01-01’ AND ‘2025-01-31’ ORDER BY a.submitted_at DESC; this returns a predictable result set you can feed into both merge fields and exports.

Merge fields are simply templated accessors into that queried result set; think of them as keys that map to a specific entity.field. When you compose an email or letter, reference the correct scope explicitly—application-scoped values must come from Application.status or Application.submitted_at, and person-level labels from Person.first_name or Person.primary_email. If you mix scopes incorrectly (for example using Person.status where you intended Application.status) you’ll send stale or misleading content. Always include fallback logic in templates (for instance a default label when a value is null) and test templates with representative joined rows so you validate token resolution before mass sends.

Performance and correctness are tightly coupled when generating merge-field-driven communications. Naive per-record lookups create N+1 query patterns that kill throughput; instead, batch-resolve entities with a single joined query and stream the result into your mail-merge engine. For large sends, paginate on an indexed predicate (submitted_at DESC) and materialize a staging table that contains all fields needed for templating—id, email, latest_application_status, program_name—so the mailer reads one well-formed row per recipient and does not re-run joins mid-send.

Exports are where your modeling trade-offs become visible to analysts and external systems. You must decide whether exports are “wide” (one denormalized row per person containing latest_application_* columns) or “tall” (one row per application or per TestResult). Use wide exports for dashboard-friendly aggregates and single-row lookups; use tall exports when analysts need event-level detail or when you must preserve history. Be explicit in export specs about grouping keys; for a tall export include person_id, application_id, created_at, and source_system so downstream joins remain deterministic.

Practical export implementation details prevent a lot of late-stage firefighting. Always include primary keys and foreign keys in CSV headers (for example person_id, application_id, testresult_id), include provenance columns (source_system, imported_at), and expose computed summaries when analytics teams request fast reads (latest_decision, application_count). If you denormalize, codify the reconciliation logic that builds denormalized columns—describe which query creates latest_application_status and how often it’s refreshed—so analysts can trust the exported values.

Finally, operationalize validation and permissions. Create acceptance tests that render a sample of merge-field emails, verify exported row counts against source counts (one-to-many expectations), and scan exports for sensitive columns before sharing. Restrict exports that contain review content to segmented roles, and ensure merge-field templates cannot reference fields outside a recipient’s permission scope. When you treat querying, merge fields, and exports as three coordinated artifacts of the same entity model, you eliminate most surprises in migration and day-to-day operations.

Taking this concept further, our next step is to translate these query shapes into concrete import/export templates and test queries so we can prove end-to-end behavior with representative data and iterate on index choices and denormalization strategy.