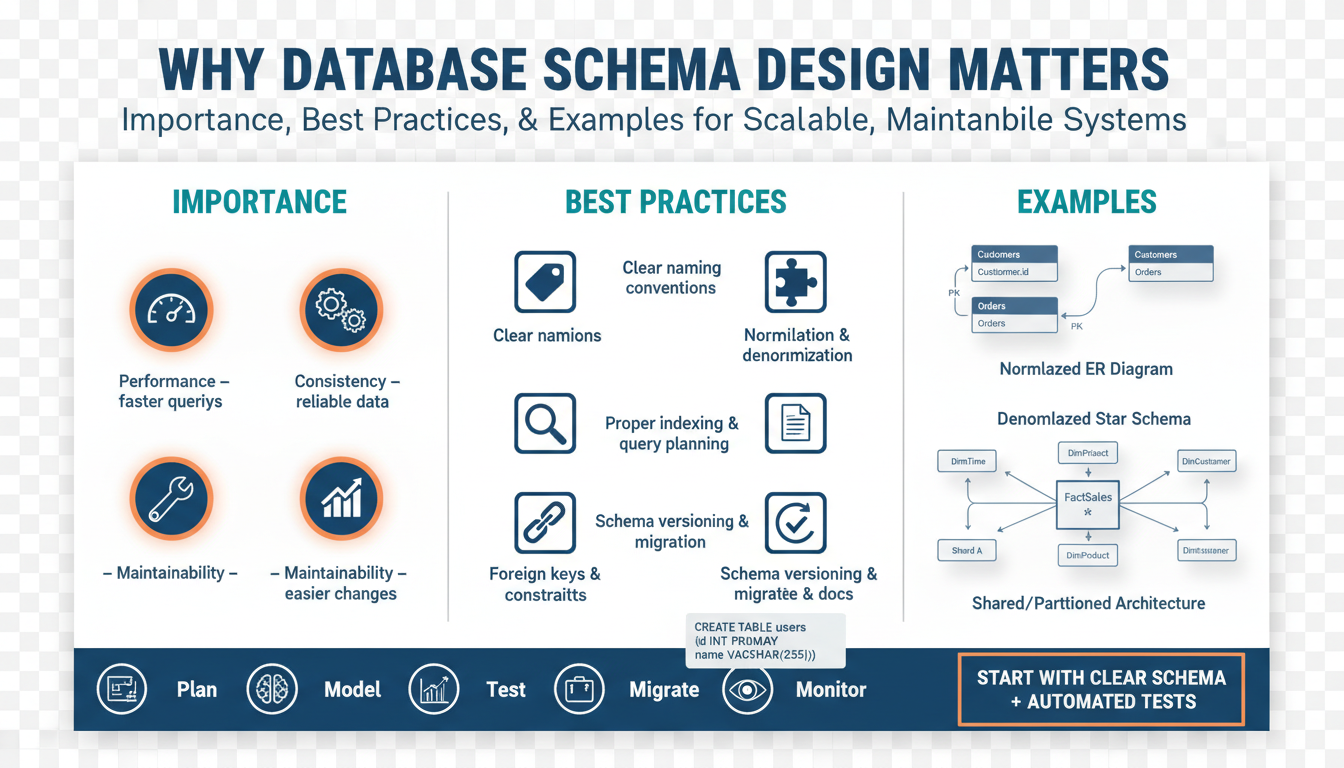

Why Database Schema Design Matters

When your app slows to a crawl under real traffic, the problem often isn’t the language or the framework—it’s the shape of your data. Database schema design sits at the intersection of correctness, performance, and long-term agility, and getting this right early changes how you build features and respond to incidents. We use the term database schema design to mean the organized structure of tables/collections, column types, constraints, indexes, and relationships that define how your application stores and retrieves data. Good design prevents expensive surprises; poor design forces costly rewrites.

Building on this foundation, let’s be specific about why structure matters. Normalization—organizing data to eliminate redundancy—protects consistency by reducing the number of places you must update when a business rule changes. Denormalization (introducing controlled redundancy) is a deliberate trade-off to reduce join complexity and improve read performance for high-throughput queries. Index design affects latency and I/O patterns directly: a poorly chosen composite index can turn a 10ms lookup into a full-table scan that costs seconds. Understanding these trade-offs is core to practical database schema design.

Concrete examples make those trade-offs real. In an e-commerce system, representing an order as a normalized set of Order, OrderLine, Product, and Inventory tables makes transactional updates safe: when you debit inventory you update a single row within a transaction. But serving a product detail page that shows price history, review aggregates, and current stock may require multiple joins and expensive aggregates. In that case we often add a denormalized product_summary table or materialized view that precomputes joins for the read path, reducing read latency at the cost of extra writes and eventual consistency.

Scalability is another domain where schema choices matter. Sharding or partitioning strategies rely on predictable access patterns; if your primary key choice scatters related rows across nodes, joins and transactions across shards become expensive or impossible. Schema evolution matters too: rolling out a column type change across millions of rows requires an online migration strategy (backfill in batches, shadow writes, feature flags) to avoid downtime. When you design with migrations in mind—using nullable columns, versioned payloads, or a separate audit table—you reduce the operational pain of schema changes.

Developer productivity and system safety improve when schemas encode business intent. Constraints such as foreign keys, unique indexes, and CHECK constraints act as executable documentation that prevents invalid data from entering the system. How do you make this practical in a fast-moving team? Use small, reversible migrations, automated schema tests, and contract-driven APIs so that your application and database evolve together. Tools like schema diffing, CI-run migration tests, and type-safe database clients turn schema design from an afterthought into a guardrail for the codebase.

Operational visibility is the last piece of the puzzle: queries are how users experience your product, and schema determines query shapes. Properly instrumented query plans, index hit ratios, and slow-query logs let you correlate schema changes with performance regressions. Backup and recovery policies depend on schema too—large, wide tables with unbounded JSON blobs complicate incremental backups and restore times. Designing schemas that favor bounded row widths and explicit types reduces restore time objectives and lowers operational risk.

Taken together, these points show that schema design is not a purely academic task; it directly affects latency, scalability, developer velocity, and operational resilience. As we move into examples and migration patterns, we’ll apply these principles to real-world refactors so you can see how small schema choices cascade into major system behaviors. By thinking of the schema as a living contract between your data, your code, and your operational processes, we keep systems maintainable and scalable as requirements change.

Data integrity and constraints

Data integrity is the contract between your application logic and the source of truth — the database schema — and constraints are the executable terms of that contract. From the first read path we design to the millionth transactional write, constraints like primary keys, foreign keys, UNIQUE indexes, NOT NULL and CHECK rules encode invariants that you cannot reliably enforce only in application code. Building on this foundation, treat the schema as active enforcement rather than passive documentation: it prevents invalid states, reduces debugging surface, and makes intent visible to every developer and operator who inspects the database schema.

Start by understanding what each constraint class guarantees and when to use it. Primary keys guarantee row identity and implicitly improve query plans; unique constraints enforce business uniqueness such as email or SKU; foreign keys (referential integrity) link related records and let the database reject orphaned rows; CHECK constraints express value-level rules (ranges, enum membership, simple invariants). Some databases offer richer primitives — for example, exclusion constraints or JSON-schema-like checks — that are useful for domain-specific invariants. When you name and apply these constraints deliberately, your database schema becomes a first line of defense against corruption.

Why put rules in the database instead of only in the application? The main reasons are single source of truth and protection against concurrency hazards. When two services attempt simultaneous updates, application-level checks can race and let invalid states slip through unless you add complex locking logic or distributed transactions. For example, in an order/inventory flow we discussed earlier, a foreign key plus a transactional decrement on inventory ensures that an order cannot reference a non-existent product and that stock decrements are atomic — something application checks alone struggle to guarantee under load.

Constraints do have operational trade-offs, so we choose them where invariants are critical. Every constraint adds work to writes: UNIQUE and FK checks often require index lookups and can slow bulk loads. To manage that cost, use patterns like deferrable constraints for multi-row transactions, staged validation when adding new rules, or partial indexes to scope rules to a subset of rows. Example SQL patterns you can apply in PostgreSQL are:

ALTER TABLE payments

ADD CONSTRAINT fk_order

FOREIGN KEY (order_id) REFERENCES orders(id)

DEFERRABLE INITIALLY DEFERRED;

ALTER TABLE orders

ADD CONSTRAINT fk_product

FOREIGN KEY (product_id) REFERENCES products(id)

NOT VALID; -- add quickly, validate after backfill

ALTER TABLE orders VALIDATE CONSTRAINT fk_product;

These patterns let you preserve integrity without taking systems offline for large backfills or bulk imports.

Schema evolution and constraints must be planned like migrations. Adding a tight CHECK or UNIQUE on a column with historical exceptions will fail if you run it naively; instead, backfill and clean data in controlled batches, add the constraint in a non-valid or disabled state (if your DB supports it), and then validate after the backfill. When you remove or relax constraints, document the reason and add compensating monitoring so you don’t silently reintroduce invalid data. Treat constraints as part of your deployment contract and include them in migration tests so CI signals whether a change will break production.

How do you detect when a constraint is masking an upstream bug? Instrument violation counts, slow queries, and failed-constraint logs in your observability stack; a sudden increase in attempted constraint violations often indicates a client or service regression. In CI, include schema-aware tests that insert invalid rows expected to be rejected, and run property-based or contract tests that exercise edge conditions. These tests turn constraints into actionable feedback loops rather than surprising runtime failures.

In practice, use constraints to enforce core invariants and rely on application logic for complex workflows that require orchestration or eventual consistency. Where we denormalize for read performance, maintain shadow writes and reconciliation processes so data integrity can be verified and repaired. By encoding the non-negotiable rules in the database schema and treating constraints as living parts of your architecture, you reduce incident blast radius and make future refactors and migrations far more predictable — next we’ll examine migration patterns that preserve these guarantees while you evolve your data model.

Normalization vs denormalization decisions

Building on the schema principles we’ve already covered, choosing between normalization and denormalization is a pragmatic performance and correctness decision you make as part of database schema design. Normalization—reducing redundancy to protect consistency—keeps writes simple and transactional, while denormalization—introducing controlled redundancy—optimizes hot read paths for latency and throughput. Early in a project you should default toward normalization to preserve invariants and make migrations safer; later, identify read-heavy hotspots where denormalization measurably improves read performance without unacceptable operational cost.

Decide based on workload characteristics and failure modes rather than ideology. If your access pattern is write-heavy or requires strong transactional guarantees (for example, financial transfers or inventory decrements), normalization preserves correctness and reduces reconciliation work. If you serve product detail pages, dashboards, or search results where latency dominates and exact immediate consistency is not required, denormalization or precomputed aggregates can cut p99 read latencies by orders of magnitude. Ask yourself: what are the read SLAs, how often do writes occur, and how costly is a stale read vs a failed write? Those answers should drive whether you introduce redundancy.

Use well-understood denormalization patterns instead of ad-hoc duplication. Materialized views or summary tables (precomputed joins/aggregates) are safe, auditable forms of denormalization because you can refresh or rebuild them predictably. Event-driven projections—where a change stream publishes domain events and a consumer builds denormalized views—scale well and separate read-path concerns from transactional writes. A typical materialized view pattern in SQL looks like:

CREATE MATERIALIZED VIEW product_summary AS

SELECT p.id, p.name, latest_price(p.id) AS price, count(r.id) AS review_count

FROM products p

LEFT JOIN reviews r ON r.product_id = p.id

GROUP BY p.id;

-- refresh concurrently when appropriate

REFRESH MATERIALIZED VIEW CONCURRENTLY product_summary;

When you go async, design reconciliation and idempotency up front because eventual consistency is now part of your contract. Implement idempotent consumers, include version or event sequence numbers on projections, and schedule reconciliation jobs that compare authoritative normalized rows to denormalized copies and repair drift. For example, an event consumer should apply updates only when event.position > last_applied_position and write the last_applied_position atomically with the view update; this pattern prevents duplicate processing and simplifies recovery after outages.

Operational trade-offs must be explicit: denormalization increases write amplification, storage, and complexity for schema evolution. Every additional column or summary table means more places to modify during migrations and more potential for stale reads, so instrument and monitor accordingly. Track write latency, the rate of delayed or failed projection updates, reconciliation drift (rows repaired per hour), and the proportion of reads served from denormalized views versus primary joins. Tests in CI should include dual-write simulations and reconciliation runs to ensure migrations don’t silently break views.

When should you normalize instead of denormalize? Default to normalization for safety, auditability, and when constraints matter; choose denormalization when profiling shows clear read-path bottlenecks that cannot be fixed with indexing, query tuning, or caching alone. Adopt an incremental approach: normalize first, profile in production, introduce targeted denormalized views behind feature flags, and roll back easily if reconciliation cost or stale-read rate is unacceptable. Dual writes and a controlled backfill let you validate the new read model before switching traffic.

Ultimately, treat denormalization as a tool to shape query patterns, not a shortcut to avoid understanding them. When we denormalize deliberately—using materialized views, event-driven projections, or compact summary tables—we trade write cost for predictable read performance while keeping integrity checks and reconciliation processes in place. Next, we’ll apply these patterns to concrete migration workflows so you can introduce denormalized views safely and measure their operational impact.

Indexing and performance optimization

When a single endpoint turns p99 latency into a user-facing outage, the problem is often the shape of your queries and the indexes that support them. Building on the earlier discussion of normalization and denormalization, we treat indexing as the practical lever that converts schema choices into predictable read latency. If you want reliable query performance, you must think about index strategy early and measure regularly so read SLAs hold as data grows.

An index is a data structure that lets the database find rows without scanning every page; common implementations are B-tree for range and equality lookups and GIN/GiST for full-text or array membership. On first use, define selectivity as the proportion of distinct values for a column—high selectivity makes an index more effective. Partial indexes (which index only rows that match a predicate) and covering indexes (which include additional columns to satisfy queries without a lookup) give you more precise control over I/O and can dramatically reduce read amplification. We recommend you name these patterns explicitly in schema reviews so the trade-offs between read latency and write cost are visible to the team.

Index design begins with the queries, not the tables. Inspect your slow-query logs and profile representative queries with EXPLAIN ANALYZE to see whether the optimizer uses an index or falls back to a sequential scan. For composite indexes, column order matters: place the most selective, frequently-filtered column first and the next most selective columns after it; for example, a common pattern on an events table is:

CREATE INDEX ix_events_userid_type_ts ON events (user_id, event_type, created_at DESC);

This index supports queries that filter by user_id and event_type while sorting by created_at without an extra sort step. If your queries only filter by event_type occasionally, consider a separate partial index scoped to hot event types instead of a wide composite index that bloats writes.

Indexes are not free: they increase write latency, consume storage, and require maintenance (vacuuming or compaction depending on your engine). Monitor index bloat, write amplification, and index hit ratio alongside query latency; a rising write latency or falling hit ratio often signals misapplied indexes or changing data distribution. We also recommend using automated tests that run representative workloads in CI so migrations that add indexes can be measured for both read improvement and write impact before deployment.

Indexing is one of several performance optimization tools; knowing when to add an index versus when to change the query or introduce a materialized view is critical. How do you decide? Start by measuring: if EXPLAIN shows a sequential scan caused by lack of a selective predicate, an index is usually the right fix. If the query requires expensive joins or aggregations across many rows and you serve that result frequently, a materialized view or a denormalized summary table will often outperform additional indexes because it reduces CPU and read I/O at the cost of more complex writes.

Treat optimization as an iterative workflow: identify the offending queries, reproduce them on a staging copy with realistic statistics, test candidate indexes and rewrites, then deploy behind a feature flag or small traffic cohort. When you add an index, validate the optimizer’s choice with post-deployment EXPLAINs and observe whether cache hit rates and p95/p99 latencies improve. If an index isn’t being used, don’t leave it indefinitely—remove it or convert it to a partial/covering index to reduce write cost.

Taking this concept further, combine index strategy with partitioning and targeted denormalization for high-cardinality workloads. Partition large tables to minimize scanning scope and place indexes on the active partitions to keep index sizes manageable. By choosing indexes that map to your most common query shapes and by measuring their operational cost, we turn indexing from a guess into a controlled instrument of performance tuning — next we’ll examine migration patterns that let you add, validate, or remove these structures safely in production.

Partitioning and sharding strategies

When your normalized schema and carefully tuned indexes still choke under growth, partitioning and sharding become the next levers to restore latency and throughput. Building on the schema decisions we’ve already discussed, you should treat partitioning and sharding as deliberate data-layout patterns that align physical storage with access patterns. Partitioning and sharding directly affect query shapes, joins, and maintenance windows, so we choose them to reduce I/O, constrain searches, and keep indexes small as data grows. Early in design, think about these patterns in terms of scalability and operational cost—not as a last-minute hack.

How do you pick a partition key? The most important rule is to base the choice on query frequency and locality: pick a key that groups rows accessed together. For time-series logs, range partitioning by a timestamp lets the engine prune old partitions quickly and drop them as a retention operation; for multi-tenant services, list or hash partitioning by tenant_id isolates noisy tenants. If your traffic is skewed, a pure range key can produce hot partitions, so consider composite partition keys or hash-prefixing to distribute writes while preserving locality for common queries.

Range, hash, and list are the typical partitioning patterns you’ll use in a single-node DB. Range partitions group contiguous key ranges (useful for time and sequence), hash partitions spread rows across N buckets to reduce write hot spots, and list partitions map explicit discrete values to partitions. Each pattern has trade-offs: range simplifies range scans and archival, hash reduces skew but makes range queries across buckets harder, and list gives explicit control for known categories. When you implement partitions, ensure your queries include the partitioning predicate so the planner can prune partitions and avoid scanning inactive segments.

Sharding takes the concept of partitioning across nodes: each shard is an independent database instance holding a subset of the data. Choose a shard key that minimizes cross-shard operations because distributed joins and two-phase commits are expensive and brittle. A common pragmatic approach is to co-locate related entities (for example, user profile, sessions, and activity rows) on the same shard using a stable user_id or tenant_id. When you must reference global data—catalogs, reference tables—keep those small and replicated rather than sharded to avoid cross-shard lookups.

Operationally, resharding is the hard part and must be planned up front. Adopt online resharding strategies: route writes to a coordinator service that can dual-write to old and new shards, migrate ranges incrementally, and keep a monotonically increasing mapping so reads consult the correct shard. Consistent-hashing techniques help when you want to scale horizontally with minimal remapping, but they complicate deterministic range queries. Whatever approach you choose, instrument migration progress, maintain idempotent apply logic, and test recovery paths for partial failures.

Partitioning and sharding interact with indexes, backups, and schema migrations in ways you must account for. Keep indexes local to partitions when possible to reduce index size and maintenance windows; schedule partition-level maintenance (vacuuming, compaction) during low-traffic windows to avoid global locks. For schema changes, roll out column additions and backfills per-partition or per-shard, validating as you proceed so that a single bad migration doesn’t force a system-wide rollback. Monitor partition pruning effectiveness, partition size distribution, and cross-shard query rates so you can detect skew or hotspot formation early.

Taken together, these layout choices give you predictable scalability: partitioning reduces scan scope and improves maintenance, while sharding spreads storage and CPU across nodes. As we move to migration patterns and operational playbooks, we’ll apply these layout strategies to concrete rollout plans—showing how to add partitions, split shards, and validate correctness without interrupting the critical read and write paths of your application.

Evolving schemas and migrations

When you need to change a column type, add a high-cardinality index, or introduce a denormalized view without taking the app down, the hard part isn’t the SQL — it’s the rollout plan. Building on our database schema design principles, we treat schema evolution and schema migrations as operational features of the system, not one-off chores. We design changes to be reversible, observable, and incremental so you can measure impact and limit blast radius when traffic is real and data volumes are large.

Start by declaring backwards-compatible stepwise changes as the default approach. A safe migration sequence separates schema change from behavior change: first add nullable columns or new tables, then populate and validate data off-line, then switch application logic via feature flags, and finally remove the old artifacts. This pattern supports online migrations because each step keeps both old and new models usable; when something goes wrong you flip the flag or stop the backfill, minimizing customer-visible risk. How do you change a column type on a multi‑terabyte table without downtime? You follow the same sequence and measure each phase.

Implement a dual-write / backfill pattern for any non-trivial transformation. Begin by adding the new column or table and updating writers to write both formats (dual-write) behind a controlled feature flag; then run idempotent backfills in small, monitored batches to populate historical rows. A minimal SQL sketch looks like:

ALTER TABLE orders ADD COLUMN total_cents_new bigint;

-- application writes both total_cents and total_cents_new

UPDATE orders SET total_cents_new = total_cents WHERE total_cents_new IS NULL LIMIT 10000;

-- repeat until done, then switch reads to total_cents_new

This code pattern keeps the critical read path stable while you migrate; it also provides a clear rollback: stop writing the new column and continue reads from the old one. For very large tables, run backfills partition-by-partition or per-shard to keep transaction sizes bounded and to let the planner prune work. Use batching with idempotent updates so retries are safe and resource usage is predictable.

Constraints and indexes need their own choreography because they directly affect write latency and validation cost. When adding a foreign key or unique constraint, prefer non-blocking approaches where supported: create the index concurrently, add the constraint as NOT VALID (or equivalent), then validate after the backfill. For example, adding a FK with deferred validation prevents long locks and lets you correct offending rows in targeted batches. If your DB lacks non-blocking semantics, consider a side-table of violations or a reconciliation job so the migration can proceed without stalling writes.

Monitoring and safety nets matter as much as the migration steps. Instrument the backfill with progress metrics (rows processed, error rate, time per batch), surface constraint violations and replication lag, and track read p99/p99.9 latencies before and during the migration. We also recommend smoke tests that compare representative reads from old and new models and automated reconciliation jobs that sample and repair drift. Include circuit breakers in your deployment pipeline so automated rollback is possible when thresholds are breached.

Testing migrations in CI and staging is non-negotiable if you want confident rollouts. Create migration tests that run against production‑like datasets (or realistic synthetic clones), validate the dual-write path, exercise roll-forward and roll-back scenarios, and run query plans to ensure indexes and partitioning behave as expected. Contract tests that assert both schemas satisfy the same read-side expectations catch many integration surprises early and reduce the need for emergency fixes in production.

Finally, make schema change a team discipline rather than a solo task: document the migration plan, the expected operational signals, and the rollback criteria; schedule the work with stakeholders who own consumers of the data model; and treat migrations as first-class deployables in your CI/CD pipeline. Taking this approach turns schema evolution into a predictable capability — you’ll be able to evolve the schema, deploy online migrations safely, and keep your system resilient as requirements change.