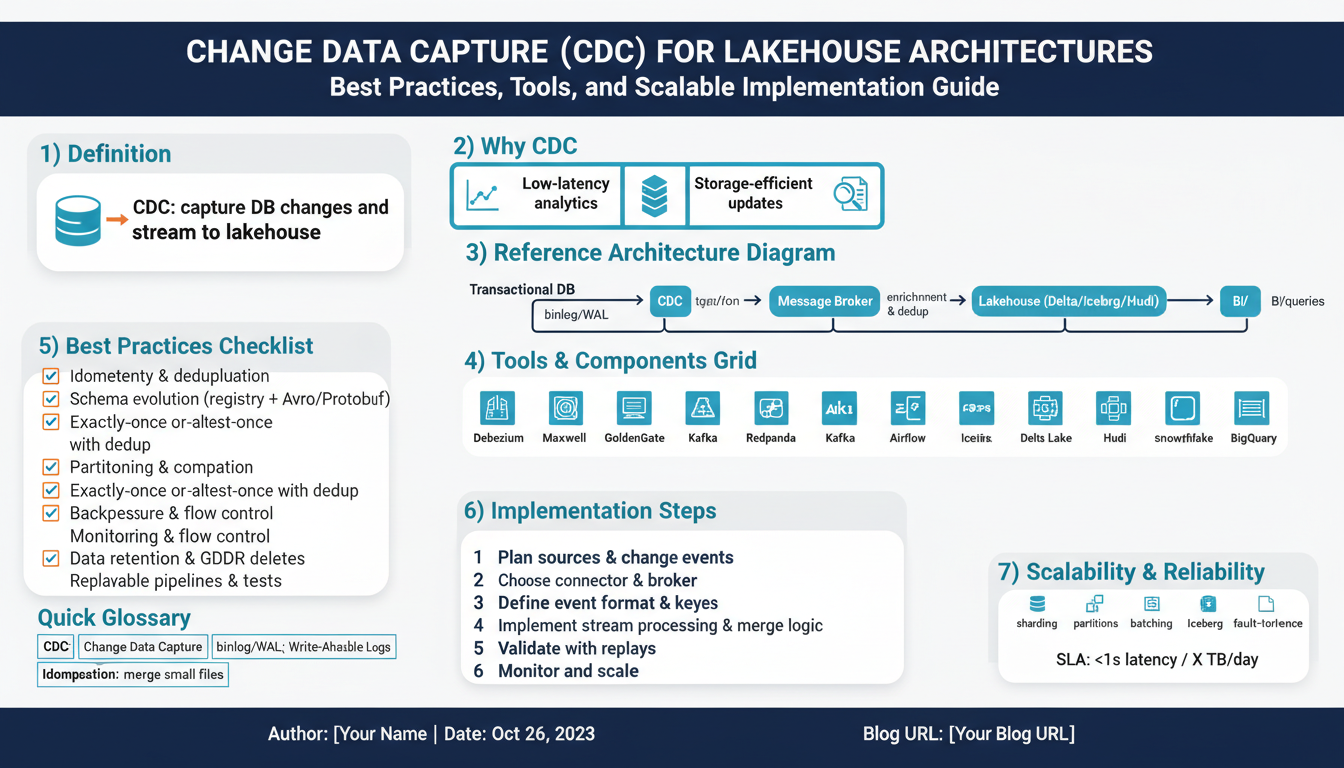

Why CDC for Lakehouse Architectures

Building on this foundation, adopting Change Data Capture (CDC) becomes the pragmatic bridge between transactional systems and a responsive lakehouse. CDC lets you capture row-level inserts, updates, and deletes from your OLTP stores and stream them into the lakehouse with low latency, keeping analytical tables near-real-time without expensive full-table scans or nightly batch windows. If you care about timely analytics, accurate state, and minimizing downstream recompute, CDC gives you a clear operational and cost advantage over snapshot-based ingestion.

Traditional batch ETL treats the source as immutable between runs, which forces frequent full-table scans, long pipelines, and brittle backfills. CDC flips that model: you record a stream of changes (insert/update/delete) and apply only those deltas to your analytical storage. How do you keep your lakehouse fresh without heavy full-table scans? By applying change events incrementally and deterministically, you reduce compute, network I/O, and the risk of inconsistent intermediate states — critical for high-throughput systems like order processing, inventory sync, or fraud detection.

Correctness is non-negotiable when you apply CDC to a partitioned file-based store. We treat each event as an idempotent mutation: use a stable primary key, an ordering token (LSN, timestamp, or CDC offset), and an upsert/merge pattern on the target table so repeated events or replays don’t corrupt state. For example, when using a transactional table format you can apply a compact MERGE pattern to reconcile changes safely:

MERGE INTO sales_agg AS T

USING (SELECT id, total, last_update FROM cdc_buffer) AS S

ON T.id = S.id

WHEN MATCHED AND S.last_update > T.last_update THEN

UPDATE SET total = S.total, last_update = S.last_update

WHEN NOT MATCHED THEN

INSERT (id, total, last_update) VALUES (S.id, S.total, S.last_update)

This pattern enforces deterministic conflict resolution while leveraging the lakehouse’s atomic commits; use monotonic offsets or log sequence numbers to guarantee ordering across retries and checkpoints. Moreover, batch your CDC events by partition key (date, tenant, region) to avoid small-file proliferation and to make compaction predictable and efficient.

Scalability considerations drive implementation choices. Streaming platforms like Kafka or managed change-streams scale ingest and provide back-pressure control, while connectors (Debezium, cloud change streams) translate DB redo logs into structured CDC events. On the sink side, choose an append/merge-friendly table format (Delta, Iceberg, or Hudi) to get transactional writes and time-travel. In high-volume workloads — ad-tech impressions, retail spikes, telemetry — prefer micro-batches or bulk-apply windows to amortize write overhead, then compact and optimize files asynchronously to preserve read performance.

CDC also unlocks governance and lineage benefits you otherwise lack with blind snapshots. Each change event is an auditable record: you can reconstruct a row’s history, implement point-in-time restores, and show exact provenance for reporting or compliance. That capability is invaluable for investigations, reproducible analytics, and regulatory requirements like data access requests or rollback scenarios. We often pair CDC streams with metadata tracking (event versions, schema IDs) so schema evolution becomes explicit and reversible.

Operational trade-offs matter: CDC increases architectural complexity, requires robust monitoring (lag, error rates, schema drift), and can incur licensing or egress costs depending on your connectors and cloud provider. Choose CDC when your update/delete churn, latency SLAs, or analytical fidelity justify the operating cost; for low-change, large-batch sources a periodic snapshot may be sufficient. Taking this concept further, next we’ll examine tooling and patterns that make CDC reliable and maintainable at scale, including connector choices, idempotency strategies, and observability practices.

CDC Capture Methods: Log vs Triggers

Building on this foundation, choosing how you capture changes is one of the most consequential design decisions for reliable, low-latency ingestion into a lakehouse. Do you read the database’s transactional log or implant logic inside the database with triggers? That trade-off shapes latency, ordering guarantees, operational surface area, and the cost of ownership. In this section we compare the two patterns—log-based CDC and trigger-based CDC—so you can pick the right capture method for your workload and constraints.

Log-based CDC reads the database’s redo/transaction log (WAL, binlog, or equivalent) and emits committed changes as a stream. This approach observes changes after the database has determined commit order, which preserves transactional ordering and reduces application-visible interference; it also lets you attach monotonic offsets (LSN, binlog position) useful for deterministic replays and idempotent downstream merges. Connectors such as Debezium or cloud-managed change streams commonly translate these logs into Kafka topics or cloud event streams so you can scale consumers independently and batch apply to the lakehouse with predictable offsets.

Trigger-based CDC installs triggers or stored procedures on tables to capture DML operations at execution time and persist change rows to a side table or event queue. Triggers give you immediate, table-level control: you can enrich, filter, or augment events inline and guarantee that emitted payloads include application-derived context that isn’t visible in raw logs. However, triggers execute inside the transaction path and therefore increase write latency and CPU for OLTP workloads; they also multiply schema maintenance work because every schema evolution typically requires trigger updates or redeployments.

Compare practical trade-offs along the axes that matter. For throughput and minimal impact on OLTP, log-based CDC usually wins: it offloads processing to connectors and supports high-throughput, partitioned ingestion with ordering guaranteed by the log offset. For tight integration with legacy systems where you don’t control log access or when you must include computed columns and business logic at capture time, triggers can be a pragmatic fallback. In terms of correctness, logs give a cleaner ordering token (LSN/binlog offset), while trigger-based streams require you to create your own sequence or monotonic timestamp to safely apply MERGE operations in the lakehouse.

In real-world pipelines we often implement a hybrid operational pattern. Use log-based CDC as the primary, high-throughput path and reserve triggers for niche tables where you must capture derived context or enforce specialized audit semantics. Pipe log events into a durable intermediary (Kafka, Kinesis, Pub/Sub) partitioned by primary key or tenant, buffer and compact into micro-batches, then apply deterministic MERGE/UPSERT into Delta/Iceberg/Hudi tables using the log offset as the ordering token. For tables behind triggers, normalize the emitted payload to the same event schema and attach an ingestion sequence so downstream consumers treat both sources uniformly.

So how do you decide in practice? Favor log-based CDC when you need scale, minimal transactional interference, and robust ordering via LSNs; choose triggers when you lack log access, need inline enrichment, or must operate on legacy platforms. Evaluate performance impact with a short pilot: measure commit latency, CPU on primary DB, and end-to-end lag into a staging table. Taking this step prepares you to select connectors, craft idempotent upsert strategies, and plan observability—topics we’ll tackle next as we examine tooling, connector configuration, and operational best practices for production-grade CDC into a lakehouse.

Tools and Connectors Overview

Building on this foundation, choosing the right connectors and integration tools is one of the highest-leverage decisions you’ll make when operationalizing Change Data Capture for a lakehouse. Many projects stall not because CDC is theoretically hard, but because connector choices mismatch the source semantics, throughput requirements, or downstream merge patterns. We want tools that preserve ordering tokens, support schema evolution, and let us batch or micro-batch events for efficient file writes to Delta, Iceberg, or Hudi tables. Early in the pipeline these trade-offs determine end-to-end latency, cost, and correctness.

At a high level the pipeline has three connector roles: the capture connector that reads the source (log or trigger output), the streaming or queue layer that buffers and partitions change events, and the sink/ingest connector or job that materializes those events into the lakehouse. Capture connectors (for example, log-tail readers or vendor change streams) must expose a monotonic offset (LSN, binlog position, change token) and stable primary-key metadata so downstream MERGE operations are deterministic. The streaming layer—Kafka, Kinesis, Pub/Sub, or managed equivalents—gives you partitioning and replay semantics; the sink layer can be Kafka Connect sinks, Structured Streaming/Flink jobs, or managed ingest services that write into transactional table formats.

Which connector should you pick for a PostgreSQL OLTP workload? Prioritize a connector that reads the WAL and exposes the commit LSN and schema ID, because that ordering token simplifies idempotent MERGE semantics in the lakehouse. For high-throughput systems you’ll typically reach for Debezium or a cloud-managed change stream that supports logical decoding and produces a canonical envelope (before/after payload, op type, LSN). If you’re on a platform without log access, you may accept trigger-based capture but plan to attach a monotonic ingestion sequence in the emitted payload so merges remain deterministic.

Mapping CDC events to lakehouse upserts requires careful transformation and a schema-management strategy. We recommend using a schema registry and a compact envelope format (Avro/Protobuf/JSON with metadata) so every event carries primary_key, op_type, commit_offset, and schema_id fields; this makes downstream reconciliation and time-travel queries predictable. When you implement the sink, use the commit_offset as your merge ordering token and include idempotency keys to tolerate retries. For example, design your consumer to buffer events by partition key (date, tenant) and produce micro-batches that run a single MERGE per partition to avoid small-file churn and to exploit atomic commits in Delta/Iceberg/Hudi.

Operational resilience depends on connector features: exactly-once delivery (or well-understood at-least-once semantics), SMT/transformation support, dead-letter handling, and observability hooks. Use Single Message Transforms or stream processors to normalize fields, drop noisy columns, and attach ingestion metadata before sink writes. Put in place a dead-letter queue for schema-errors, and surface connector lag, retry rates, and producer/consumer throughput into your monitoring system. For heavy write workloads, consider transactional sinks (Flink or Spark Structured Streaming with two-phase commits) or batched write jobs that reconcile offsets atomically with table commits.

In production scenarios like multi-tenant order processing or telemetry ingestion, connector tuning becomes a critical lever. Increase batch size and compress payloads to reduce per-event overhead, tune flush intervals to balance latency versus file sizes, and partition events by tenant or date to simplify compaction. We also recommend asynchronous compaction jobs that merge small files and rewrite partitions after high-change periods so analytical queries stay performant. These tuning knobs—batch size, parallelism, checkpoint cadence—are often the difference between a stable CDC pipeline and one that accrues technical debt.

As we discussed earlier when comparing log-based and trigger-based capture, your connector choices should implement the ordering and idempotency guarantees you relied on in the MERGE patterns. Next, we’ll dig into concrete connector configurations, idempotency strategies, and observability patterns so you can move from design to a resilient, measurable CDC pipeline into your lakehouse.

Storage Formats and Table Engines

Building on this foundation, choosing the right on-disk layout and table engine is one of the most consequential operational decisions for CDC-driven lakehouses. The storage format you pick determines atomicity, time-travel, compaction behavior, and how efficiently you can apply MERGE/upsert workloads that arrive from your CDC stream. Early in a pipeline you need to ask: will you favor fast small-file writes and asynchronous compaction, or larger atomic commits with built-in versioning? That choice shapes ingestion latency, read amplification, and the cost model for compaction and storage.

At the file-layer we prefer transactional table formats that explicitly model commits and file manifests because they make idempotent CDC application straightforward. Formats such as Delta, Iceberg, and Hudi (each mentioned intentionally) embed metadata that maps files to table state, enabling atomic replace/commit operations and reliable time-travel. With these formats you can use the commit offset (LSN or CDC sequence) as your merge ordering token and rely on the format’s snapshot isolation to avoid partial-state reads during concurrent writes. That guarantees the deterministic MERGE pattern we recommended earlier without building heavyweight concurrency control in your consumer code.

Table engine selection matters as much as file format; engines provide the runtime semantics for writes, compaction, and query optimization. If you run a query engine that supports native ACID on top of the storage format—Spark with Delta Lake, engines using Iceberg’s table metadata, or Hudi’s incremental read APIs—you get tighter integration for upserts, clustering, and small-file management. Engines also differ in how they expose pragmas for compaction, file-size targets, and partition evolution, so tune engine-level settings to align with your CDC pattern: frequent small batches need aggressive background compaction, while larger micro-batches can defer rewrite jobs for off-peak windows.

Practical ingestion patterns arise from pairing a format and engine to real workload characteristics. For high-update tables with hotspot keys (e.g., customer profiles or inventory counts) partition by a stable shard key and use clustering or Z-ordering where supported to reduce rewrite scope during compaction. For wide, append-heavy event streams, design partitions by ingestion date and let engine-level compaction roll up small files into larger columnar files optimized for analytics. In both cases, expose the commit_offset and schema_id as table-level columns so downstream consumers can audit applied events and reconcile gaps without scanning entire partitions.

Operationally, monitor three storage-level metrics: small-file count per partition, average file size, and commit latency for atomic transactions. High small-file counts signal you should increase micro-batch size or enable more aggressive write buffering in the connector; low average file size hurts scan throughput and increases per-query open-file overhead. Commit latency indicates whether your engine’s metadata operations (manifest writes, snapshot updates) are becoming the bottleneck—if commits stall, back-pressure will accumulate in the CDC buffer and end-to-end lag rises. Use these signals to tune batching, compaction frequency, and parallelism in ingestion jobs.

When you evaluate trade-offs, favor table formats and engines that give you explicit guarantees you can reason about under retries and replays: snapshot isolation, deterministic file-replacement semantics, and visibility control for uncommitted state. How do you pick between Delta, Iceberg, and Hudi for your workload? Run a short pilot that measures end-to-end latency, small-file churn, and compaction cost under production-like CDC rates, then prefer the combination that minimizes rework and keeps read performance steady. Taking this approach prepares you to configure connector batching, compaction jobs, and downstream query engines—topics we’ll examine next to turn these format choices into scalable, observable ingestion pipelines.

Building a Scalable CDC Pipeline

When you move beyond nightly snapshots, the hard part isn’t capturing changes — it’s applying them at scale while preserving correctness and read performance. Change Data Capture gives you a stream of row-level deltas that, when applied deterministically, keep analytical state fresh without repeated full-table scans. In a lakehouse this reduces recompute and enables near-real-time analytics, but only if you design ingestion to handle ordering, idempotency, and file-level churn from the start.

Building on this foundation, start by isolating three durable surfaces: capture, buffer, and apply. How do you preserve ordering and scale consumers without creating hotspots? Use a log-based capture that emits a monotonic offset for each transaction and buffer those events in a partitioned, durable queue so you can replay or backfill without touching the source. Partition by logical shards (tenant, customer_id hash, or date) and keep the partitioning scheme aligned between the queue and the target table to minimize cross-partition MERGE work and to enable parallel, idempotent applies.

Batching strategy drives throughput and small-file behavior, so design your micro-batches around both event volume and target file-size goals. Group change events into micro-batches that cover a single partition and include the commit offset range used as the ordering token; then run a single MERGE/UPSERT per micro-batch to amortize metadata commits and produce larger columnar files. For high-cardinality, low-churn tables favor larger batches (seconds-to-minutes) and asynchronous compaction; for hotspot keys where latency matters, prefer smaller, frequent batches but combine them with targeted compaction and clustering to avoid rewrite storms.

Make idempotency and deterministic conflict resolution first-class primitives in the apply stage. Use the source LSN/offset or an ingestion sequence as the authoritative ordering token and store it as a table column; deduplicate incoming events on (primary_key, commit_offset) before merge. When using transactional table formats, reconcile replays and retries by making each MERGE idempotent — include last_update or commit_offset in your WHEN MATCHED predicates so later stale events never overwrite newer state. If you need per-record exactly-once semantics, consider transactional sinks or two-phase commit frameworks that reconcile queue offsets with table commits atomically.

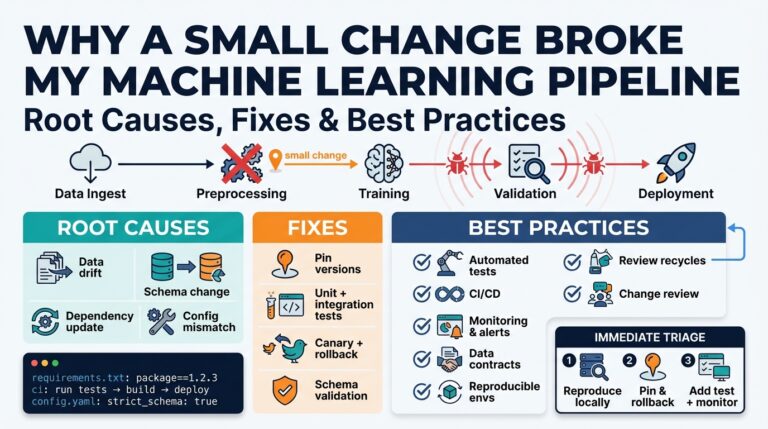

Operational resilience requires observability, back-pressure control, and schema governance. Instrument connector lag, partition consumer lag, merge failure rate, small-file counts, and commit latency so you can correlate upstream spikes to downstream compaction needs. Implement dead-letter routing for schema errors and use a schema registry to manage evolution; negotiate schema changes by evolving the consumer with explicit schema IDs and a compatibility policy so your apply logic can skip or coerce incompatible fields instead of failing the pipeline. Automate health checks and circuit-breakers that pause ingestion to a partition if commit latency or failed merge rate exceed thresholds.

Finally, scale with parallelism and pragmatic sharding rather than monolithic throughput. Scale consumers horizontally per partition, schedule background compaction and file-rewrite jobs after peak windows, and expose commit_offset and schema_id as audit columns so consumers can fast-verify applied ranges during recovery. In practice, for an e-commerce order stream we shard by order_id hash, buffer events for 30–60 seconds into partitioned micro-batches, then run parallel MERGE jobs that finish with a quick compaction pass — this pattern reduces end-to-end lag, avoids small-file proliferation, and keeps analytical queries performant. Taking these patterns together prepares you to pick connectors and tuning knobs that match your throughput and latency SLAs in the next section.

Idempotency, Ordering, and Monitoring

Building on this foundation, CDC for a lakehouse demands that you treat idempotency, ordering, and monitoring as first-class engineering concerns from day one. If you replay a CDC stream or retry failed writes, how do you guarantee the same sequence of changes yields the same table state? We start by making idempotency explicit in the schema and the apply logic: expose the source commit_offset (LSN/binlog position) and an idempotency key on every event, store the highest applied offset per partition in the target table, and enforce merge predicates that only accept newer offsets. These concrete fields let you deduplicate incoming events deterministically and reason about replays without ad hoc logic.

Idempotency is more than de-duplication; it’s a contract between capture and apply. Implement an idempotent MERGE that checks commit_offset in the WHEN MATCHED clause (for example, only update when incoming_offset > target_offset) and persist the applied_offset as a table column so retries become no-ops. For high-throughput tables you can combine a short-lived dedup buffer in memory or Redis keyed by (primary_key, commit_offset) with the persistent offset stored in the table to avoid racing writes. This approach makes retries, consumer restarts, and connector duplications tolerable because the sink enforces the canonical state transition.

Ordering guarantees determine how simple your idempotency logic can be. Use a log-based capture that preserves a monotonic ordering token (LSN, binlog position, or Kafka offset) and align your partitioning between the queue and table so that ordering is local: partition by hashed primary_key, tenant_id, or another stable shard. When events arrive out of order because of retries or cross-partition writes, buffer them long enough to allow late arrivals up to your SLA, apply within a commit-offset window, and then advance the watermarks. For latency-sensitive hot keys you may accept per-key serial processing (single-threaded consumer per shard) to guarantee strict ordering; for bulk workloads you can parallelize at partition granularity while still preserving deterministic merges.

Monitoring ties idempotency and ordering into operational stability; without observability you can’t detect or recover from corruption. Track connector lag, consumer partition lag, max and min commit_offset applied per partition, merge failure rate, and small-file counts in the target partitions. Alert when consumer lag exceeds a fraction of your SLA or when commit latency and failed-merge rates rise together, because that pattern often signals metadata contention during atomic commits. Surface dead-letter queue size and schema-error rates and build dashboards that correlate upstream offsets to downstream applied_offset ranges so you can quickly identify partitions that need backfill or manual reconciliation.

Recovery and replay workflows should be automated and auditable. When a partition falls behind or you need to reapply a range, compute the gap as (source_high_offset – target_applied_offset) per shard and run idempotent micro-batch replays constrained to that offset window. Validate the result with lightweight checksum queries or sample-based row-level comparisons rather than full-table scans; for example, compare counts and max(timestamp) per primary key bucket to detect anomalies. Keep a compact audit table that records ingest job run_id, offset_range, file_manifest_hash, and success flag so engineers can trace exactly which micro-batch produced a given commit and roll it back or replay it reproducibly.

Taking this concept further, make ordering and idempotency visible to your SLOs and make monitoring actionable: automations should throttle upstream capture or pause ingestion to a partition when commit latency or failed merge rate exceed safe thresholds, and background compaction jobs should be scheduled after large replays. As we move into connector configurations and tuning, we’ll use these monitoring signals and offset columns to decide batch sizes, compaction cadence, and when to promote two-phase commits for stronger delivery guarantees.