Defining Analytics Engineering and Scope

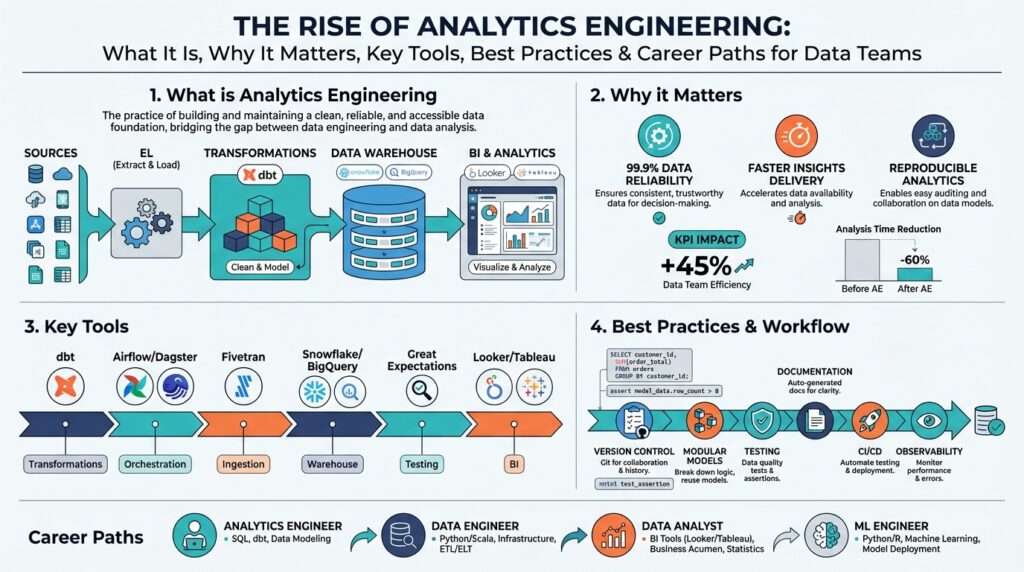

Building on this foundation, we need a precise, practical definition so you can decide where to invest engineering effort and team skill. Analytics engineering is the discipline that turns raw ingestion into trusted, documented datasets ready for analysis, sitting squarely between data engineering and analytics/BI. It centers on repeatable transformations, data modeling, and reliable metric definitions inside the data warehouse, using tools like dbt and orchestrators to run and test transformations as code. What does an analytics engineer actually do day-to-day?

At its core, the role is about ownership of the transformation layer and the metric contract that downstream consumers rely on. You design and implement data models (the organized, query-ready representations of raw events and sources), author transformation code, write tests for data quality, and document semantics so analysts and product teams can self-serve. This work includes establishing semantic consistency—so the same “orders_revenue” calculation produces identical results in dashboards, notebooks, and product reports—and building observability around pipeline freshness and schema drift.

Technically, scope is defined by the stack and the interfaces you commit to support. In most teams, analytics engineering owns ELT-style transformations inside the data warehouse, authored in SQL or a transformations-as-code tool such as dbt, while data engineering manages ingestion, streaming, and storage. For example, a dbt model might select from a raw events table and produce a conformed orders table with tests for nulls and surrogate keys:

-- models/staging/orders.sql

select

id as order_id,

user_id,

cast(created_at as timestamp) as created_at,

total_amount

from raw.events_orders

where event_type = 'order_created'

We add schema and uniqueness tests, run these models in CI, and deploy them with an orchestrator so downstream marts always rely on tested artifacts.

A useful way to think about scope is as layers: raw ingestion -> staging (one-to-one cleaning) -> core models (conformed dimensions and facts) -> marts (domain-optimized tables for analytics/BI). In practice, you’ll be the team translating product events into canonical entities, creating slowly changing dimension (SCD) patterns where needed, and ensuring performance (indexes, clustering keys, partitioning) for query costs. In a retail example, you’ll build a canonical product dimension normalized across SKU feeds, reconcile marketplace IDs, and expose a single product table that every report references.

Deciding organizational placement matters. Centralized analytics engineering yields consistent metrics and faster shared tooling, while federated or embedded engineers increase domain knowledge and reduce handoffs; both approaches require guardrails. Weigh trade-offs: central teams simplify governance and SLOs for data freshness, whereas embedded engineers speed iteration but need strong cross-team standards and automated testing. Choose based on velocity needs, size of the data surface, and how critical semantic consistency is for decision-making.

Finally, scope should be outcome-driven and measurable. Deliverables you’ll own include production-tested transformation code, a documented metric catalog, data quality monitors with SLOs, and version-controlled deployment pipelines; success metrics include reduced mean-time-to-detect for data incidents, higher query adoption of canonical tables, and fewer downstream reconciliation tickets. How do you measure success in your org? Use those metrics to tighten scope iteratively and avoid scope creep into raw ingestion or application-level event instrumentation unless you have explicit alignment with data engineering.

Taking this definition forward, we’ll examine practical tooling and patterns to implement these responsibilities reliably. In the next section, we’ll map common tools to the layers above and show concrete CI/CD and testing patterns you can apply immediately to raise data trust and delivery velocity.

Why Analytics Engineering Now Matters

Building on this foundation, the reason analytics engineering matters right now is simple: velocity and trust no longer trade off. Analytics engineering surfaces as the discipline that lets you move faster without eroding the semantic contract teams depend on, and that matters because organizations are asking for near-real-time answers, cross-functional product metrics, and repeatable analytics at scale. By embedding repeatable transformations, metric definitions, and data quality checks directly in the data warehouse and treating them as code, you reduce manual reconciliation and shorten the loop from event to insight. This is not academic; it changes how product, finance, and growth teams operate day-to-day.

The immediate drivers are technical and organizational at once. Cloud warehouses and cheap storage mean you can centralize data, but centralization without guardrails creates chaos—duplicate “revenue” metrics, inconsistent user counts, and fragile dashboards proliferate. Meanwhile, ELT patterns and tools like dbt make it feasible to own the transformation layer with software engineering practices: modular SQL, version control, and test-driven deployments. The combination of scale, improved tooling, and higher business stakes makes analytics engineering an operational necessity rather than a nice-to-have.

Practically, analytics engineering reduces cognitive overhead for consumers of data. When you enforce a single canonical model for customers, orders, or sessions and publish that model with tests and documentation, downstream analysts and product teams stop reinventing joins and aggregations for every report. This decreases duplicated work, lowers query costs by encouraging reuse of optimized tables, and produces more reliable machine learning features because feature creators draw from the same vetted sources. The result is faster, more confident decisions and fewer firefighting tickets.

Why does this matter for business outcomes? Because inconsistent metrics create tangible risk: mismatched revenue numbers stall go/no-go launches, divergent funnel definitions skew prioritization, and undetected schema drift can break billing pipelines. How do you reduce time-to-insight while keeping metrics consistent? By treating metric definitions as first-class artifacts—declared in code, covered by tests, and surfaced in a metric catalog that both engineers and analysts can reference. In practice, a well-maintained metric contract prevents the classic “my dashboard says X, your notebook says Y” debate during planning reviews.

The team and governance implications are immediate and actionable. You’ll need role clarity—who owns transformations, who owns ingestion, who approves semantic changes—and lightweight processes that let domain experts propose changes without bypassing quality gates. Choose an organizational model that fits your velocity needs: centralized teams excel at consistency and SLO enforcement, while embedded analytics engineers accelerate domain-specific iteration; both require automated testing, CI/CD for SQL, and observability to scale. Start by codifying change processes, enforcing tests in PRs, and publishing a documented metric catalog so changes are auditable and discoverable.

From a technical-practice perspective, prioritize test coverage, modular models, and monitoring. Automate unit and integration tests for core models, run them in CI, and gate deployments on test results and freshness checks. Optimize for query performance through sensible partitioning and clustering of high-cardinality fact tables so canonical models remain practical for interactive BI. Finally, instrument observability—pipeline SLA alerts, lineage visualizations, and schema-change detectors—to catch regressions early and reduce mean-time-to-detect for incidents.

Taking these changes together, analytics engineering becomes the lever that increases data product velocity while preserving trust. In the next section we’ll map concrete tools and CI/CD patterns to the model layers you already use so you can start converting these principles into reproducible engineering work. Implementing these practices raises your team’s confidence in the numbers and turns data from a source of friction into a reliable decision engine.

Analytics Engineering Core Workflow Explained

Analytics engineering and the data warehouse are where trust and velocity meet; you design a workflow that guarantees both. Building on the foundation we’ve already discussed, start by asking a practical question: How do you structure a pipeline that balances speed and trust while remaining auditable and maintainable? The core answer is a layered, code-first pipeline where dbt-style transformations, automated tests, and a versioned metric catalog form your contract with downstream teams. Front-loading these disciplines turns ad-hoc analysis into repeatable data products you can operate and evolve safely.

The workflow begins with clear layer boundaries that you implement and enforce. First, keep raw ingestion immutable and minimal—capture event-level fidelity or source system dumps without transformation so you can always replay or re-derive. Second, build a staging layer that performs one-to-one cleaning and type normalization to create reliable inputs for modeling. Third, author core conformed models (facts and dimensions) that centralize business logic and feed domain-specific marts and a metric catalog so analysts and ML feature owners consume a single source of truth.

Treat transformations as code and design models for composability and testability. Write modular SQL models with single-responsibility: one model applies SCD handling, another computes a canonical customer record, another derives sessionization. Choose materializations deliberately—use views for debugging, tables for stable canonical artifacts, and incremental models for large, append-heavy fact tables with deterministic keys. For example, implement an incremental pattern that upserts by natural key and materializes only changed partitions so you reduce cost and preserve idempotence in backfills.

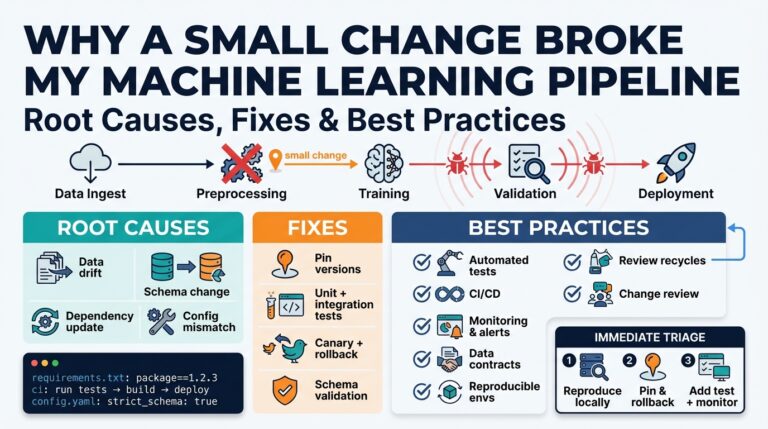

Automated testing and CI/CD are non-negotiable parts of the core workflow. Start with dbt-like unit and schema tests for nulls, uniqueness, and referential integrity, and add lineage-aware integration tests that validate aggregates against known reconciliations. Run these tests in PRs so every change to a model fails fast and leaves an audit trail; gate production deploys on passing test suites and freshness checks. Add snapshot tests for slowly changing dimensions and regression checks on critical metrics so you detect semantic drift before consumers notice anomalies.

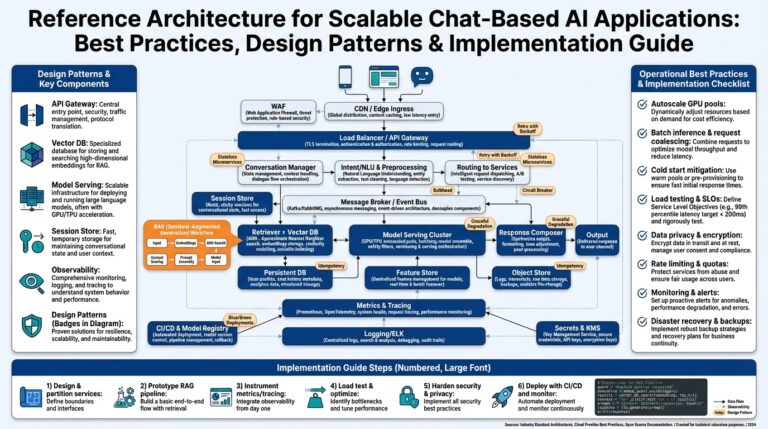

Operationalizing models requires reliable orchestration, observability, and SLOs. Schedule orchestrated runs for dependent DAGs, expose job-level and model-level freshness SLAs, and implement alerting on misses or unexpected schema changes. Surface lineage and a metric catalog in your developer portal so you can trace a dashboard number back to the canonical model and the underlying event. In practice, this means you can resolve a revenue discrepancy by comparing the same metric definition across environments, tracing transforms, and replaying a small backfill instead of hunting ad-hoc queries.

Collaboration and change management complete the workflow—this is where governance and velocity meet. Use PRs, code reviews, and change proposal templates so domain experts can propose semantic changes while engineers enforce quality gates; version your metric catalog and tag breaking changes with migration notes. Keep a lightweight approval policy for high-impact models and a fast path for low-risk fixes so you don’t bottleneck iteration. Establish a rollback plan and runbook for incidents so you can restore a previous model version quickly when a test or freshness alert catches a regression.

Taken together, this workflow converts raw data into reliable, documented datasets and shared metrics you can trust and iterate on. As we continue, we’ll map concrete tools and CI/CD patterns to each layer so you can implement these steps with minimal friction and maximum observability.

Essential Tools: dbt, Warehouses, Orchestration

Building on this foundation, the practical stack you’ll operate day-to-day centers on three capabilities: a transformations-as-code layer, a scalable data warehouse, and a reliable orchestration plane — dbt, a cloud data platform, and an orchestrator respectively. dbt is the industry-standard for authoring modular SQL models, embedding tests, and generating documentation that lives alongside your codebase, which makes transformations auditable and versionable. Treating transformations as code lets you run the same models in CI, review changes in PRs, and ship metric changes with a rollback path. (docs.getdbt.com)

Start by choosing a data warehouse with the execution and governance features your team needs. The warehouse is where your core models live, so prioritize predictable compute (isolated virtual warehouses or clusters), good support for incremental and partitioned materializations, and strong access controls that match your organizational security model; for example, Snowflake exposes virtual warehouses and a suite of administrative features to manage compute and query concurrency. Selecting the right warehouse affects cost, latency, and the kinds of materializations you can reasonably use for canonical facts and marts. Evaluate how the warehouse exposes performance tooling and cost telemetry so you can enforce SLOs on freshness and query cost. (docs.snowflake.com)

Once you’ve selected a warehouse and adopted dbt, design your models for composability and testability. Author small, single-purpose models that perform one transformation or conformance step, choose materializations deliberately (views for quick iteration, tables for stable marts, incremental for large append-heavy facts), and codify tests for nulls, uniqueness, and referential integrity in dbt so failing assertions block deployment. Document exposures and metrics in the same repo so analysts can discover canonical definitions and trace a dashboard back to a model and its test coverage. This pattern turns the warehouse into a productized layer your consumers can rely on rather than an ad-hoc pile of queries. (docs.getdbt.com)

Orchestration glues everything together — it schedules runs, enforces DAG dependencies, surfaces failures, and (ideally) captures lineage and operational metadata. How do you choose between a scheduler like Airflow and a data-aware orchestrator like Dagster? Use Airflow when you need mature, flexible Python DAGs and a broad ecosystem of operators; choose a data-aware orchestrator when observability, asset-oriented lineage, and first-class testing for data assets accelerate debugging and ownership. Both approaches let you run dbt jobs inside orchestrated flows, but they offer different ergonomics for local dev, branching deployments, and metadata-driven alerting. (airflow.apache.org)

Tie these pieces into a repeatable workflow with test-driven PRs, CI gates, and model-level SLAs. Schedule orchestrated runs that first validate staging freshness and schema assertions, then run dbt models with incremental upserts and post-run metric regression checks, and finally publish results to marts while recording lineage and cost metrics for each job. Instrument pipeline health (freshness, run duration, credit/cost per job) and expose those signals in runbooks so an SRE-style incident playbook exists for data failures. Taking this concept further, integrate cataloging and metric discovery into developer portals so product teams trace a number back to a tested, versioned model before they act — that’s how you translate engineering practices into trust and velocity for your organization.

Best Practices: Testing, Documentation, CI

Analytics engineering depends on predictable change: you want to move metrics forward without breaking downstream consumers, and that requires disciplined testing, clear documentation, and a CI pipeline that enforces your semantic contract. How do you make a change to a canonical model and be confident it won’t break twenty dashboards or a billing job? Start by treating testing, documentation, and CI as a single feedback system that prevents regressions and surfaces intent to every reviewer.

Treat tests as first-class code artifacts and embed them close to the models they protect. Unit-style assertions (null checks, uniqueness, referential integrity) validate local invariants; integration tests validate joins and aggregate-level reconciliations across models; regression and snapshot tests detect semantic drift on important metrics. In practice, implement these with dbt-like schema tests plus lightweight SQL-based integration tests that run on a small, deterministic fixture dataset in CI so you can reproduce failures locally. Add metric-regression checks that compare post-change aggregates to historical baselines (with tolerated deltas) so a changed formula fails the pipeline before it reaches production.

Make documentation discoverable and executable rather than an afterthought. Document business intent, edge cases, and the canonical calculation alongside the model—include the plain-English definition, the canonical SQL snippet, and example inputs/outputs so analysts can validate assumptions. Use docs-as-code to version the metric catalog and expose lineage from exposures back to the staging tables so consumers can trace a dashboard number to the raw event. When you change a metric, publish a migration note and bump the catalog version so downstream teams can opt into a breaking change with a clear rollout plan.

Design CI to enforce quality gates, not just to run tests for visibility. Every pull request should run style linters (SQLFluff or equivalent), execute fast unit tests, and run a scoped integration suite that exercises only the models touched by the change. Persist test artifacts and compiled models from CI so an operator can reproduce a failing run; if you use dbt, store the manifest and run_results to accelerate debugging. For heavy integration tests or full-mart builds, use staged or ephemeral environments and parallelize jobs to keep feedback times low while preserving production-like fidelity.

Combine these practices into a fast, safe feedback loop that supports small, auditable changes. Gate merges on passing tests and a documented rationale, publish a docs preview for each branch so reviewers can inspect lineage and definitions, and require metric-regression approvals for high-impact models. Keep PRs small—scope changes to a single semantic change or refactor—so tests provide actionable failure signals and rollbacks are trivial. This pattern reduces friction: you can ship a metric tweak and, if the CI fails, roll back to the last known-good artifact with confidence.

Operationalize the loop with SLOs, alerting, and clear ownership so CI and tests produce operational reliability. Define freshness and correctness SLOs for critical models, alert on test flakiness or increasing test duration, and instrument schema-change detectors to fail pipelines early when contracts shift. Assign model owners who approve semantic changes and maintain runbooks so on-call responders can triage test failures, run backfills, and communicate impact. When your team treats testing, documentation, and CI as parts of the same reliability surface, you turn analytics engineering work into a measurable, auditable engineering discipline.

Taking this approach, we make model changes deliberate and reversible—and create the scaffolding that allows us to scale metric ownership without chaos. In the next section we’ll map these patterns to concrete CI/CD configurations, orchestration practices, and tooling choices so you can implement the pipeline architecture that fits your warehouse and deployment cadence.

Career Paths and Team Structures

Analytics engineering sits at the crossroads of product insight and reliable data delivery, and your team structure determines whether that discipline scales or becomes a bottleneck. If you hire analytics engineers without defining clear ownership, you’ll get duplicated metrics, firefights over dashboard numbers, and slow incident resolution. We need to treat the transformation layer and the metric catalog as first-class products, staffed and organized to deliver SLAs on freshness, correctness, and discoverability in the data warehouse while using tools like dbt as our engineering surface.

Start by mapping career levels to concrete responsibilities so promotions are predictable and development is measurable. At entry level, an analytics engineer focuses on staging models, unit tests, and clear documentation; mid-level engineers own core conformed models, integration tests, and performance tuning; senior engineers design SLOs, mentor peers, and lead cross-team schema migrations. We should write role descriptions that call out specific competencies: SQL engineering, model design for incremental materialization, CI/CD for SQL, and production monitoring—skills that let you move from fixing ad-hoc tickets to owning a metric contract for a domain.

How do you choose between centralized and embedded team structures for analytics engineering? Centralized teams consolidate governance, run the global metric catalog, and enforce SLOs so the same revenue definition is used everywhere; embedded engineers sit with product teams to speed iteration and domain understanding but require stronger automation and shared linters to avoid divergence. A hybrid approach lets a central core maintain infra, catalogs, and cross-cutting standards while embedded analytics engineers contribute domain models and business rules, which balances semantic consistency with rapid feature delivery.

Hiring and leveling should reflect the technical breadth the role now demands. Candidates must show not only polished SQL but also experience with warehouses, incremental patterns, and orchestration concepts; familiarity with dbt is increasingly table-stakes because it encodes tests, documentation, and model lineage. Promote engineers when they demonstrate system thinking: they can trace a dashboard number to raw events, author reversible migrations, and design rollback plans for high-impact model changes. We recommend using measurable signals—test coverage, number of canonical models owned, reduction in reconciliation tickets—as part of promotion rubrics.

Career mobility is a strength you should advertise and cultivate, because analytics engineers often bridge into related tracks. A strong analytics engineer can transition into data engineering by deepening ingestion and streaming knowledge, into data science by building feature stores and experiment metrics, or into product analytics leadership by owning metric governance and stakeholder roadmaps. Encourage rotational programs and project-based cross-pollination so people build adjacent skills without interrupting operational guarantees; this both reduces burnout and creates redundancy for critical owners.

Operationally, embed ownership into day-to-day workflows so accountability is visible and actionable. Make teams on-call for model freshness and metric regressions, require PR-level documentation and docs previews for metric changes, and assign metric catalog stewards who approve breaking changes with migration notes. We should track adoption and impact—measure query reuse of canonical tables, time-to-recover for incidents, and the frequency of downstream reconciliations—to make career conversations fact-based rather than anecdotal.

Taking these organizational choices into account prepares you to map roles to tooling and CI/CD patterns effectively. Building on this foundation, the next practical step is to align job responsibilities with concrete pipelines and enforcement points—how we run dbt in CI, surface lineage from the data warehouse, and gate deployments so career growth and team structure deliver real, measurable trust in our metrics.