Understanding Missingness Mechanisms

Building on this foundation, we need to treat missingness mechanisms as a first-class modeling choice because they determine which imputation or modeling strategy will produce unbiased results. Missingness mechanisms and missing data are not interchangeable: the reason a value is missing affects whether you can recover its distribution from the observed data. If you ignore this, you risk biased feature engineering, leaky imputations, and models that perform well in-sample but fail in production.

Start by mastering the taxonomy: MCAR, MAR, and MNAR are the core categories you’ll use when reasoning about missing values. Missing Completely At Random (MCAR) means the probability of missingness is independent of both observed and unobserved data; Missing At Random (MAR) means missingness depends only on observed data; Missing Not At Random (MNAR) means missingness depends on unobserved values themselves. For example, a sensor dropout that affects readings regardless of condition is MCAR, a survey nonresponse correlated with observed demographics is MAR, and patients skipping a follow-up because their condition worsened (the unobserved outcome) is MNAR.

How do you diagnose which mechanism you’re dealing with? You cannot prove MAR or MNAR definitively from the data alone, but you can gather strong evidence. A pragmatic approach is to treat the missingness indicator as a response and fit a logistic regression or tree model using observed features as predictors. If the model explains missingness well, that suggests MAR (missingness depends on observed features). If you find no predictors that explain missingness, MCAR is plausible. If missingness persists unexplained and domain knowledge suggests dependence on the unobserved value, lean toward MNAR and plan sensitivity analyses.

Concretely, implement a quick diagnostic in Python: create a binary column missing_y = df[‘y’].isna().astype(int), then fit a classifier like sklearn’s RandomForestClassifier on observed columns. If the classifier achieves much better-than-chance AUC, you have evidence that missingness depends on observed data (supporting MAR). Use regularization or permutation importance to identify which features drive missingness. This pattern links missingness mechanisms to actionable feature engineering because the same observed predictors can be used in conditional imputation models.

When the mechanism looks MAR, favor model-based or multiple imputation approaches that condition on the predictors that explain missingness. For example, use an iterative imputer that models y | X_obs, or run multiple imputation by chained equations (MICE) to reflect uncertainty in imputations. These methods assume that the variables you conditioned on capture the missingness process. Conversely, if evidence supports MCAR, straightforward methods like mean imputation or complete-case analysis may be unbiased but less efficient; still, quantify efficiency loss and consider inverse-probability weighting if you want to retain unbiased estimation.

MNAR is the toughest case and requires explicit modeling of the missingness process or sensitivity analysis. If missingness likely depends on unobserved values, incorporate a selection model or pattern-mixture model into your pipeline, or simulate plausible MNAR mechanisms and show how estimates change. In practice we often combine domain knowledge and multiple scenarios: one optimistic (MAR-like) and one conservative (MNAR-like) imputation, then compare model coefficients, fairness metrics, or downstream performance to assess robustness.

Practically, integrate these diagnostics into your feature engineering pipeline so missingness reasoning is reproducible and auditable. Log the missingness predictors you identified, store imputation model parameters, and attach a short rationale (MCAR/MAR/MNAR) to each imputed feature. Doing so clarifies why you chose a conditional imputer, multiple imputation, or a sensitivity analysis and makes the next step—choosing transformation strategies and validation protocols—straightforward.

Diagnosing Missingness Patterns

Building on this foundation, the practical question becomes not only whether values are missing but why they are missing — because that determines which imputation and modeling choices will be defensible. Missingness and missing data can hide informative structure: a pattern that looks random in a quick summary may be systematically tied to covariates or to the outcome itself. How do you distinguish MAR from MNAR in practice? We’ll walk through diagnostics you can automate and interpret, so your downstream imputation choices are evidence-driven rather than guesswork.

Start with visual exploration to reveal obvious structure in missingness. Plot a missingness matrix (rows are records, columns are features) and a feature-wise missingness bar chart so you immediately see co-occurrence and sparsity. Complement those with heatmaps of pairwise missingness correlations and an upset-style view to surface common missing-value combinations; these visuals often expose whether missingness clusters around certain feature groups or time windows, which suggests a predictable process you can condition on during imputation. Visual inspections are quick and frequently reveal temporal, batch, or device-level drivers of missing data that require no complex modeling to detect.

Next, treat the missingness indicator as a target: build a propensity model and interrogate it. Fit a regularized logistic regression and a tree-based model to predict the binary missing indicator using fully observed covariates, then evaluate discrimination (AUC) and calibration. If models predict missingness well and specific covariates show high permutation importance or large coefficient magnitudes, you have evidence for MAR and should condition your imputation models on those predictors. Use partial dependence or SHAP plots to understand whether missingness increases or decreases across predictor ranges — that helps you design conditional imputers rather than global mean fills.

When simple predictors fail to explain missingness, look for pattern-level structure rather than single-feature associations. Cluster records by their missingness vector and then compare observed-outcome distributions across clusters; significant differences imply that missingness patterns carry signal about the data-generating process and may warrant pattern-specific imputations or separate models per pattern. For example, in clinical datasets, labs missing together often reflect protocol differences across sites: clustering by missingness can reveal site-level effects we should model explicitly rather than impute away. This approach bridges exploratory analysis and practical feature engineering by turning missingness patterns into model features when appropriate.

Include formal tests and sensitivity checks as part of your diagnosis, but treat them as complements rather than proofs. Apply Little’s MCAR test to check the plausibility of MCAR, recognizing its sensitivity to sample size and multivariate distributional assumptions; a non-significant result makes MCAR more plausible but never proves it. For situations that resist MAR diagnosis, run sensitivity analyses: implement delta-adjusted imputations or pattern-mixture simulations that shift imputed values across plausible ranges and observe how coefficients or predictions change. These bounding exercises quantify how much your conclusions depend on unverifiable MNAR assumptions and should guide whether you need selection models or robust reporting.

Finally, operationalize diagnostics in your feature pipeline so decisions are reproducible and auditable. Automate visual reports, log the top predictors from propensity models, and store cluster assignments and imputation parameters alongside the feature transformation. Establish simple thresholds (for example, model AUC > 0.7 or cluster-wise outcome divergence above a set effect size) that trigger conditional imputation, multiple imputation, or sensitivity modeling. By instrumenting these diagnostics, we keep missingness reasoning explicit, make imputation choices defensible, and create a smooth handoff to the next step: choosing the specific imputation strategy and validation protocol for each flagged feature.

Simple Imputations and Baselines

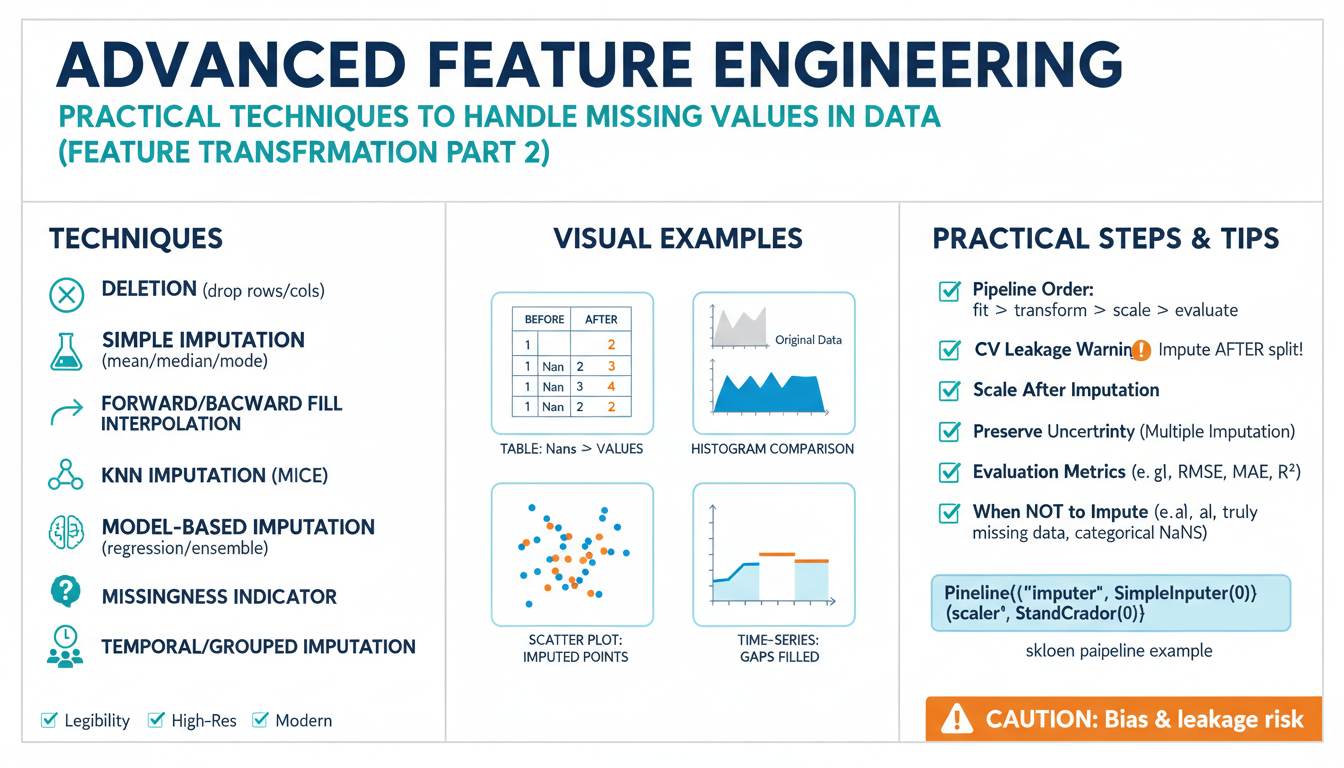

Building on this foundation, the simplest imputation and baseline strategies are the practical first tools you reach for when a dataset arrives with missing values. Simple imputation (mean, median, mode, constant) and a clear baseline imputation process give you a reproducible starting point for model development and error budgeting. How do you choose between mean imputation, median imputation, or a constant fill in practice? We use these methods to establish defensible performance baselines and to reveal whether more sophisticated conditional or multiple imputation is warranted.

A basic definition helps align expectations: simple imputation replaces missing entries with a single summary value per feature, while baseline imputation describes the minimal, reproducible strategy you treat as the engineering default. Implementations typically include mean/median for numeric columns, mode for categorical columns, and forward-fill/backfill for ordered data. In code you’ll often see patterns like df[‘x’] = df[‘x’].fillna(df[‘x’].median()) and df[‘x_missing’] = df[‘x’].isna().astype(int) to preserve missingness information; that missingness indicator frequently matters more than the imputed number itself, especially when the mechanism is MAR.

Treat baselines as experiments rather than permanent fixes: they are your null hypothesis when evaluating downstream models. For time-series telemetry, a last-observation-carried-forward (LOCF) or linear interpolation baseline makes for an appropriate benchmark; for cross-sectional surveys, median imputation often beats mean when outliers exist. In production diagnostics we commonly run a baseline pipeline that includes simple imputation plus a missingness flag, measure model lift over the baseline, and only adopt more complex imputers if they deliver meaningful gains in held-out performance or stability across sites.

Be explicit about the statistical costs of these shortcuts. Mean or median imputation reduces sample variance and biases estimates toward central tendencies, which can cause coefficient attenuation in linear models and overconfident probabilistic outputs. Constant or zero fills can accidentally inject spurious categorical levels that leak label information if missingness correlates with the outcome (an MNAR warning). Consequently, always pair simple imputations with diagnostics: compare pre/post distributions, test downstream calibration, and run sensitivity checks to quantify how much your conclusions hinge on the baseline imputation.

In practice, use simple imputations as a staged, auditable step in a reproducible pipeline. Start by logging the imputation strategy and parameters for each column and include a binary missingness indicator so models can learn any informative absence signal. For example, a compact sklearn-like pipeline looks like from sklearn.impute import SimpleImputer; imputer = SimpleImputer(strategy=’median’); X_imputed = imputer.fit_transform(X_train); X_train[‘x_missing’] = X_train[‘x’].isna().astype(int). When missingness clusters by batch or site, perform grouped cross-validation so the baseline performance reflects realistic deployment shifts rather than optimistic in-sample recovery.

A disciplined baseline protocol gives you a fast, explainable reference point and a guardrail for further work. Use simple imputation to triage features, identify where conditional imputers or multiple imputation are necessary, and document the trade-offs you accepted (bias vs. variance, interpretability vs. complexity). With these baselines in place we can now examine conditional and multiple imputation techniques that model the missingness mechanism explicitly and capture imputation uncertainty for robust inference and production readiness.

Missingness Indicators and Encoding

When a feature arrives with gaps, the first decision you make is whether those gaps are signal or noise. Missingness indicators are often the simplest and most powerful way to preserve that signal: by adding a binary flag that marks whether the value was observed, you give downstream models direct access to the missing-data pattern without conflating it with the imputed value. How do you decide when to add an indicator? If your missingness diagnostics (propensity models, cluster checks) showed dependence on observed covariates or outcome, create the flag—especially under MAR—because the absence itself can predict the target and is a legitimate feature for downstream learning. Early in feature engineering, front-load missingness encoding so the rest of your pipeline can reason about absence explicitly.

A practical implementation pattern we use is to pair an indicator with any imputed numeric column so the model can distinguish between a true low value and a filled-in substitute. In code this looks like creating df[‘x_missing’] = df[‘x’].isna().astype(int) and then imputing df[‘x’] with a median or a model-based value fitted only on training data. The indicator lets linear models avoid coefficient attenuation caused by mean/median fills and lets tree models learn asymmetrical splits where absence matters. For features with complex missing patterns—batch-level or time-windowed—we create multiple indicators (site_missing, window_missing) or cluster-derived pattern flags so we capture structured missingness rather than a single global flag.

Categorical variables require a different encoding mindset: treat missingness as a legitimate category when absence conveys meaning, or use a separate flag when you want to preserve the original cardinality. One common approach is to map NaN to a token like “MISSING” and then apply one-hot, target, or frequency encoding depending on cardinality and model class. Beware of target leakage with target encoding: perform it in a cross-fold way (out-of-fold target statistics) or use Bayesian smoothing to avoid overfitting. For high-cardinality fields that were missing in predictable clusters, an embedding layer (for neural models) that reserves a slot for missingness often yields better representations than one-hot expansions.

For numeric features, the canonical pattern is indicator + imputed value + interaction. The interaction feature is simply the product of the imputed value and the missingness flag; it lets the model learn different slopes when a value was observed versus imputed. This is particularly useful when you suspect MNAR-like behavior: the interaction allows the model to treat an imputed 0 differently from an observed 0. When using iterative or conditional imputers, fit them on training folds only and persist parameters; then create indicators from raw input during inference so the model sees the same binary signal it was trained on.

Model architecture shapes encoding choices: tree-based learners often handle missingness implicitly through surrogate splits, yet explicitly adding indicators improves interpretability and can increase stability across shifts. Linear and generalized linear models require explicit flags to avoid biased coefficients, and you should standardize imputed numeric values before interaction so regularization behaves predictably. For penalized models, consider different regularization strengths for indicators (they can be sparse but high-impact) by using group lasso or feature-specific penalties when your tooling supports it.

Operational hygiene matters: integrate both the imputer and the missingness-encoder into a single, serial pipeline so training, validation, and production inference share identical transforms. Persist the imputation model, the mapping for categorical “missing” tokens, and any pattern-cluster assignments; log the fraction of missingness per feature and alert if production drift produces unseen missingness patterns. For time-series or grouped data, compute indicators at the appropriate aggregation level (per device, per user, per session) rather than globally, because grouped missingness often encodes procedural or device faults that affect downstream fairness and calibration.

Taking this approach keeps missingness indicators and encoding out of the realm of ad hoc fixes and into repeatable feature engineering practice. By preserving absence as a first-class signal, pairing it with considered encodings and interactions, and operationalizing transforms in a disciplined pipeline, we make later choices—conditional imputers, multiple imputation, or sensitivity analysis—both evidence-driven and auditable.

Iterative and Model-Based Imputation

Building on the missingness diagnostics we discussed earlier, iterative imputation and model-based imputation give you practical ways to conditionally recover missing values while preserving uncertainty and structure. If you’ve identified MAR-like behavior from propensity models or missingness clusters, these approaches let you model y | X_obs rather than applying one-size-fits-all fills. How do you choose between iterative imputation, MICE, and bespoke predictive imputers? We’ll show when each makes sense, how to validate them, and what pitfalls to avoid in production.

Iterative imputation treats each column with missing entries as a supervised learning problem: you predict the missing values of column A using the other columns, then move to column B, and repeat until convergence. This is the operational idea behind MICE (multiple imputation by chained equations): conditional imputation models are trained in sequence and repeated multiple times to capture imputation variability. The strength of iterative imputation is that it leverages conditional relationships in the data (for example, lab A predicts lab B given demographics), so the imputed distribution better matches multivariate structure than marginal mean or median fills.

Choose iterative or model-based imputation when your missingness diagnostics indicate MAR or when missingness clusters are explained by observed covariates. If your propensity model had AUC > 0.7 or cluster analysis revealed systematic patterns, conditional imputation reduces bias compared to global fills. However, if evidence supports MCAR and you only need a pragmatic baseline, simple imputation plus a missingness indicator may be sufficient; reserve iterative imputation for when you need unbiased parameter estimates, better calibration, or when imputation quality materially affects downstream decisions.

In practice, implement iterative imputation with controlled validation: fit imputers only on training folds and evaluate imputation error on held-out observed values using realistic splits (grouped or time-based where appropriate). A compact sklearn-style pattern looks like this in code:

from sklearn.experimental import enable_iterative_imputer # noqa

from sklearn.impute import IterativeImputer

imp = IterativeImputer(max_iter=10, random_state=0)

X_train_imp = imp.fit_transform(X_train)

X_val_imp = imp.transform(X_val)

Also persist the imputer object and the missingness indicators you created before imputation so inference sees the same signals as training.

Multiple imputation extends iterative imputation by producing multiple plausible completed datasets and combining estimates to capture uncertainty; use it when you care about inference—confidence intervals, coefficient estimates, or treatment effects—rather than only point predictions. After generating m imputed datasets with MICE, pool model coefficients using Rubin’s rules to obtain variance estimates that include between-imputation variability. For predictive pipelines, you can still use multiple imputation to quantify prediction spread or to ensemble models trained on different imputations, but be explicit about how you aggregate predictions and how you report uncertainty.

Model-based imputation need not be limited to linear regressions inside MICE. You can use tree ensembles, gradient-boosted machines, or neural networks to predict missingness-conditioned values, especially when relationships are nonlinear or when interactions matter. When you go this route, beware of leakage: never train an imputer on data that includes the target labels or on the full dataset before cross-validation. Use cross-fitting or out-of-fold predictions to generate imputations for training rows so downstream models don’t inherit optimistic bias from the imputer.

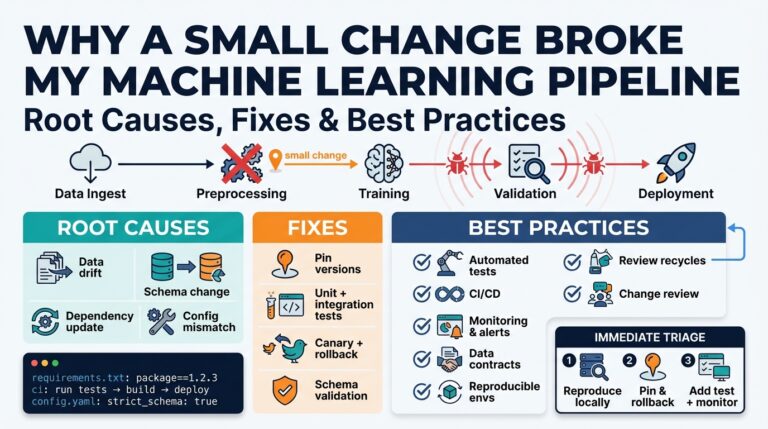

Operationalizing these methods matters as much as choosing them. Persist trained imputation models, log which features warranted iterative imputation versus simple fills, and run sensitivity analyses that shift imputed distributions to explore MNAR scenarios. For time-series or grouped data, fit conditional imputers per group or include group-level indicators so you respect nonstationary missingness. By baking iterative and model-based imputation into reproducible pipelines, we keep imputation auditable, validateable, and robust to deployment shifts—and that makes downstream modeling decisions defensible and repeatable.

Evaluating and Validating Imputations

Poor-quality imputation silently wrecks downstream reliability: a model that looks good in-sample can be learning artifacts created by your fills rather than signal. Building on our missingness diagnostics, you should treat evaluation as a formal experiment: mask a fraction of observed values, run your imputer, and measure how well recovered values match truth. How do you know when an imputer is doing more harm than good? Start by treating imputation and missingness validation as a repeatable, auditable step in the pipeline rather than an afterthought.

A straightforward, high-signal test is out-of-sample masking. Reserve 5–20% of non-missing entries per column, remove them, and apply the same transform you’ll use in production; then compute RMSE or MAE for numeric features and classification metrics (accuracy, log-loss) for categorical features. Complement point-error metrics with distributional comparisons — for example, compute the one-dimensional Wasserstein distance or a two-sample KS test between observed and imputed distributions — because low RMSE can still mask shifted tails. In code a compact pattern looks like this: select mask = np.random.rand(len(col)) < 0.1, hold_true = col[mask].copy(), col[mask] = np.nan, fit your pipeline on the training fold, then rmse = np.sqrt(((hold_true – col_imp[mask])**2).mean()). Use grouped or time-based masking when you expect batch- or time-dependent missingness so evaluation matches deployment conditions.

When you use multiple imputation methods, validation must include uncertainty checks as well as point accuracy. Generate m completed datasets and evaluate whether between-imputation variance is meaningful relative to within-imputation variance: if pooled parameter intervals are too narrow, your imputer understates uncertainty and you risk overconfident decisions. Check prediction-interval coverage on held-out values — for example, what fraction of true values fall inside the 95% predictive intervals produced across imputations — and inspect whether pooled estimates (using Rubin’s rules) shift compared to single-imputation estimates. These diagnostics tell you whether multiple imputation is capturing genuine uncertainty or merely adding noise.

Validating imputations also means measuring downstream impact. Fit your target model on data with and without the advanced imputer and compare held-out AUC, calibration curves, and metric stability across cross-validation folds and data slices (sites, cohorts, time windows). We care less about absolute imputation RMSE than about whether the chosen strategy changes decisions: does calibration drift, do top-k predictions reorder, or do subgroup performance gaps widen? Treat fairness, calibration, and business-driven KPIs as first-class evaluation targets and instrument them in your validation harness so imputation choices are judged by operational outcomes, not surrogate error alone.

For cases that may be MNAR or otherwise fragile, run sensitivity and tipping-point analyses rather than hoping diagnostics will catch everything. Implement delta-adjusted imputations where you systematically shift imputed values by plausible offsets and observe how model coefficients or predictions move; a tipping-point analysis answers the practical question “how extreme must the MNAR effect be to alter our decision?” If small deltas flip key outcomes, you must either collect additional data, adopt selection-models, or report bounded conclusions. These exercises quantify robustness and communicate uncertainty to stakeholders in concrete terms.

Finally, operationalize evaluation so validation is reproducible and prevents leakage. Always cross-fit imputers when evaluating model performance, persist imputer objects and masking seeds, and add telemetry for missingness rates and distributional drift in production. Establish simple thresholds that trigger re-evaluation (for example, held-out RMSE increase > 10% or predictive-interval coverage falling below target) and log the rationale for the chosen method (diagnostic AUC, cluster evidence, or sensitivity results). By treating imputation evaluation as an engineering-grade validation loop we keep transforms auditable and make the next step—selecting conditional imputers, iterative methods, or reporting sensitivity bounds—decidable and defensible.