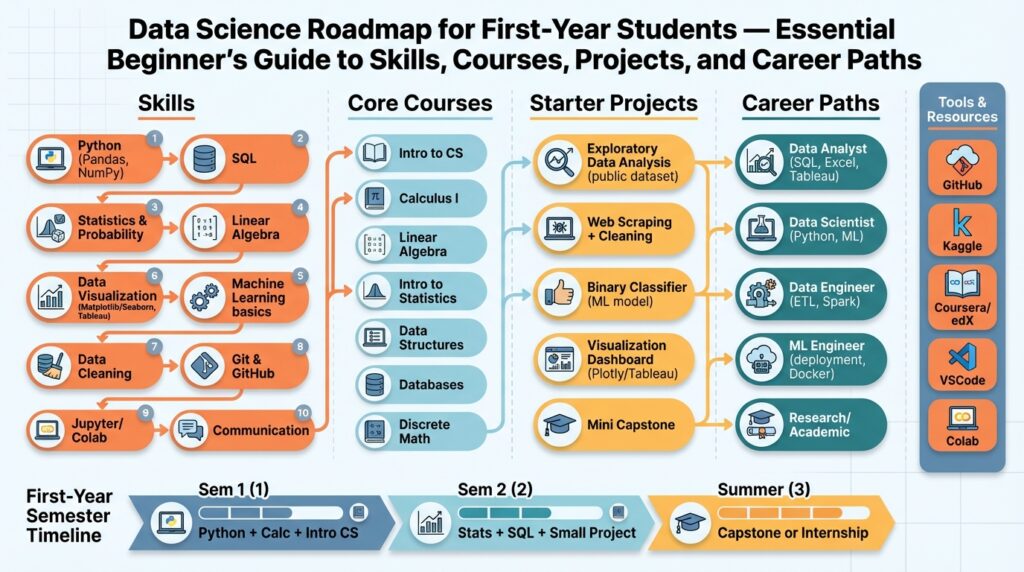

Data Science: Overview for First-Years

If you’re starting out in data science as a first-year student, treat the next two years as a skills incubator rather than a job hunt. Building on this foundation, focus on core technical pillars: data science fundamentals, Python programming, basic statistics, and an introduction to machine learning. Ask yourself early and often: How do you turn a messy CSV into a reproducible insight that a team can act on? That question should drive course choices and project selection from day one.

Data science combines statistical thinking, computational tools, and domain knowledge to extract actionable insights from data. We define terms on first use: statistics is the study of data variability and inference; machine learning is the set of algorithms that learn patterns from examples; data engineering covers the pipelines that move and transform data. Understanding these distinctions helps you pick a path—whether you want to engineer reliable pipelines, build models that generalize, or craft dashboards that influence decisions.

Start by building a compact, practical skill set that maps to real tasks you’ll do in internships and beginner roles. Learn Python as your primary language and get comfortable with pandas for data wrangling (for example, df = pd.read_csv(‘data.csv’) and df.dropna()). Pair Python with SQL for querying relational datasets and with a basic statistics course that covers distributions, hypothesis testing, and confidence intervals. These building blocks let you perform exploratory data analysis and justify why a result is meaningful, not just surprising.

Work on small, end-to-end projects that force you to practice the entire pipeline: ingest, clean, feature engineer, model, evaluate, and communicate. A first project might be a classification task—predicting loan default—where you split data (train_test_split(X, y, test_size=0.2)), fit a logistic regression, and report precision/recall rather than only accuracy. Implementing a simple model and producing a short technical write-up or notebook demonstrates both technical competence and clear communication, which recruiters value more than isolated coursework.

Choose tooling and workflows that mirror professional practice so your work scales beyond notebooks. Use Jupyter for early exploration but move reproducible code into scripts and a Git repository as soon as you repeat a workflow. Learn virtual environments or Conda, and try containerizing a small pipeline later to understand dependency management. These practices teach you how experiments become production-ready systems and prepare you for collaboration with engineers and product teams.

Finally, think about career signals and sequencing: aim for two to three portfolio projects, a GitHub repo with clean notebooks and READMEs, and at least one internship or research experience by the end of sophomore year. Decide whether you enjoy modeling, building data systems, or communicating insights—each path has different course emphases and project types. Building on this foundation, we’ll next explore specific coursework, recommended projects, and a semester-by-semester roadmap to help you move from concepts to hired candidate.

Essential Math and Statistics Foundations

Building on this foundation, start by treating math and statistics as the language that makes your models interpretable and defensible. In the first 100–150 words here we emphasize math and statistics because they let you move from “it works” to “we understand why it works.” If you’ve used pandas and run a simple logistic regression notebook, you’re ready to connect those practical steps to the underlying probability, linear algebra, and calculus that determine when models generalize and when they overfit.

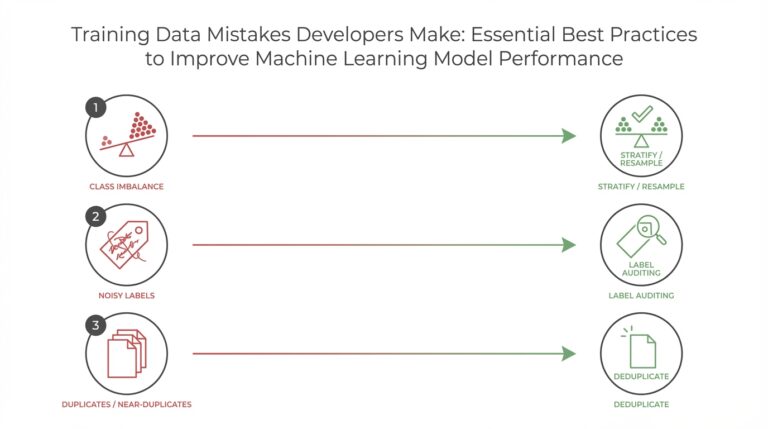

Probability theory is where you learn to formalize uncertainty and priors (a prior is your belief about a quantity before seeing data). Study random variables, expectation, variance, conditional probability, and Bayes’ rule; these concepts explain why smoothing, Laplace correction, and Bayesian updating matter in real datasets with sparse classes. Use examples like class-imbalance in fraud detection to see probability at work: prior probabilities shift expected precision and recall, and understanding that shift guides feature engineering and thresholding decisions.

Linear algebra gives you the vocabulary for features and models: vectors, matrices, dot products, eigenvalues, and singular value decomposition (SVD). These are not abstract chores—they explain why PCA (principal component analysis) compresses correlated features and why embeddings capture semantic structure. Practically, center your data with X_centered = X - X.mean(axis=0) and inspect np.linalg.svd(X_centered) when you want to reduce dimensionality before training a model; doing so often improves stability and training speed on real-world tabular and text features.

Calculus and optimization explain how models learn. Derivatives tell you how a small change in parameters affects the loss; gradients point you to the fastest decrease. Implementing gradient descent from scratch for a least-squares or logistic loss clarifies concepts like learning rate, convergence, and saddle points that matter when you scale to neural nets. Recognize convex problems (unique optimum) versus non-convex problems (multiple local minima); this distinction guides whether you worry about global optimality or practical convergence diagnostics.

Inferential statistics (the practice of drawing conclusions from data) is what you use to validate findings and communicate uncertainty. Learn hypothesis testing, p-values, confidence intervals, and statistical power and apply them to A/B tests, model-comparison, and feature-ablation studies. How do you decide whether to trust a model’s result? Compute confidence intervals for your metric (bootstrapping works well for non-normal metrics), run sanity checks that your data split is stratified, and perform power calculations when planning experiments so you avoid false negatives.

Put these tools into projects rather than memorizing formulas. Reproduce a small A/B analysis end to end: estimate treatment effect, compute a 95% confidence interval, and report whether the effect is practically significant. For model work, run PCA or an SVD-based feature reduction before fitting a logistic regression, and implement a gradient-descent optimizer to observe learning dynamics. Use numpy, scipy, statsmodels, and scikit-learn as the bridge between theory and practice. By weaving math and statistics into projects you not only learn techniques—you build the intuition to choose the right tool for a given dataset and question.

Programming Languages and Tools for Beginners

Start by matching languages and tools to the concrete tasks you’ll do as a beginner: data ingestion, cleaning, exploratory analysis, simple modeling, and communication. We recommend front-loading Python, SQL, pandas, and Jupyter early because they map directly to those tasks and to common internship expectations. How do you decide which language or tool to use for your first project? Focus on interoperability and reproducibility—choose tools that let you iterate quickly while producing artifacts (notebooks, scripts, git history, Dockerfiles) you can show to others.

Choose Python as your primary programming language when you need broad library support and integration with production systems. Python’s ecosystem gives you numpy for numerical work, pandas for tabular manipulation, scikit-learn for classical models, and lightweight ML tooling when you move beyond prototypes. Illustrate a typical pandas pattern by grouping and aggregating before modeling: df_agg = df.groupby(‘region’, as_index=False).sales.mean(); this small step often reveals feature shifts or data-quality issues that change how you engineer features. We use Python because it lets us prototype in a notebook and then migrate the same codebase into scripts or services.

Treat SQL as the lingua franca for querying structured datasets stored in relational systems or data warehouses. You should be able to express joins, aggregations, and window functions fluently: for example, SELECT user_id, COUNT() AS events FROM events WHERE event_date >= ‘2025-01-01’ GROUP BY user_id HAVING COUNT() > 5. Use SQL when data volume favors pushdown to the database; push heavy aggregations to the DB and then pull smaller, modeled slices into pandas for feature engineering. We often combine SQL and Python in the same workflow using pandas.read_sql or an ORM like SQLAlchemy so queries become reproducible steps in a pipeline.

Decide where to explore vs. where to harden your code: Jupyter is ideal for exploration and storytelling, while an IDE such as VS Code or PyCharm is better when you convert analysis into reusable modules. Keep exploratory notebooks for EDA and then extract repeated logic into scripts or Python packages; a practical pattern is to develop a notebook, refactor functions into src/data_cleaning.py, and import them back into the notebook. Use version control from day one—create a feature branch with git checkout -b feature/data-cleaning, commit incremental changes, and push frequently so your GitHub history documents your process.

Manage dependencies and reproducibility with virtual environments and containers so your work runs elsewhere. Create an isolated environment with conda create -n ds101 python=3.10 pandas scikit-learn jupyterlab, or use python -m venv .venv and pip install -r requirements.txt for smaller projects. When you need to demonstrate exact reproducibility or integrate with CI, containerize the pipeline with a simple Dockerfile; Docker captures OS-level dependencies that conda or pip alone won’t. We recommend adding a short README and a reproducible run script so reviewers can reproduce your results without guesswork.

Apply these choices in a small end-to-end project so you practice tool transitions: write a SQL extraction that reduces data size, load the result into pandas for cleaning and feature engineering, prototype models in a Jupyter notebook, refactor predict functions into a script, and capture environment details with a conda yaml or Dockerfile. This workflow trains you to think about trade-offs—when to use SQL for scale, when to use pandas for flexibility, and when to harden code in an IDE for reuse. Building these habits now makes your projects interpretable, sharable, and ready for the next step in the roadmap.

Recommended Beginner Courses and Paths

Building on this foundation, the quickest way to turn curiosity into capability is to pick a small, deliberate set of beginner courses that map to real tasks you’ll do in internships and entry-level roles. Start with core data science building blocks—Python programming, a practical statistics course, and an introduction to SQL—because these three let you extract, clean, and reason about data from day one. Front-loading these skills makes it possible to complete end-to-end projects within a semester, which is the signal recruiters actually look for on GitHub and resumes. How do you sequence them so your coursework produces demonstrable work rather than just grades?

Begin with an applied Python for data analysis class that emphasizes pandas and scripting rather than language theory. In that class we recommend exercises that force you to load a dataset, clean missing values, and produce a reproducible notebook; for example, use pandas to inspect distributions and pivot tables before modeling. Pair that with an introductory statistics course that covers probability, sampling distributions, hypothesis testing, and confidence intervals—these concepts are the reasons you can trust or challenge a model’s output. Simultaneously take a hands-on SQL lab so you can push aggregations into the database and avoid pulling unnecessarily large tables into memory.

After those foundations, take a course that connects math to models: linear algebra and introductory calculus tailored for data work. These help you understand why PCA compresses correlated features and why gradient behavior matters when you train models. Follow with an applied machine learning course that prioritizes classical methods—logistic regression, decision trees, and cross-validation—over deep learning in the first year; this reduces complexity while maximizing transferable intuition. We want you to graduate from “it runs on my laptop” experiments to honest evaluations: learning to compute precision/recall and bootstrap confidence intervals in that second course is more valuable than training a black-box model without error analysis.

Use a semester-by-semester path to keep momentum: fall semester focus on Python + intro statistics, spring semester add SQL + an applied ML or data visualization course. In the following year, schedule linear algebra and a course in data engineering fundamentals (ETL, basic pipeline tooling) while you build two portfolio projects. That sequencing gives you the chance to iterate: prototype in notebooks early, then refactor repeatable code into scripts, tests, and a reproducible environment in year two. You’ll know you’re ready for higher-level electives when you can explain why you normalized a feature, why you chose a particular model, and how you validated your evaluation metric.

Pair each course with a compact, end-to-end project so coursework becomes evidence of skill. For example, after an introductory statistics and Python pair, build an A/B analysis: estimate a treatment effect, compute a 95% confidence interval, and write a short reproducible notebook that shows data extraction, cleaning, and inference. After SQL and applied ML, implement a small classification pipeline that extracts features in SQL, engineers them in pandas, and reports model performance with confusion matrices and ROC curves. These portfolio projects make your learning visible and give you artifacts to discuss in interviews.

Depending on the early path you enjoy, steer your electives deliberately: choose more modeling and probability-focused courses if you prefer machine learning research and product experimentation; choose database systems, distributed systems, and a software engineering class if you lean toward data engineering; choose human–computer interaction and visualization courses if analytics and dashboards excite you. Each path benefits from the same early core (Python, statistics, SQL) but diverges in intermediate coursework and project types. We find students advance fastest when they pick one specialization by the end of sophomore year and then choose two projects that reflect that focus.

These recommendations intentionally prioritize practical, project-centered learning so you can show measurable outcomes quickly. In the next section we’ll convert this course list into a semester-by-semester roadmap that maps specific project milestones to the classes you should take and the artifacts you should ship.

Starter Projects to Build Practical Skills

When you move from coursework to doing real work, the quickest way to demonstrate competence is by shipping portfolio projects that mirror tasks you’ll encounter in internships. Start with compact, end-to-end projects that force you to ingest, clean, feature-engineer, model, evaluate, and communicate—these are the same stages hiring managers expect to see. Building on the foundations we covered (Python, SQL, statistics, and reproducible workflows), pick project scopes small enough to finish in a few weeks but rich enough to surface real trade‑offs. These practical data science projects teach reproducibility, version control, and how to trade off simplicity for robustness.

Choose projects with clear, testable questions and accessible data; this makes progress measurable and stories defensible. How do you pick a first project that shows both technical rigor and product thinking? Favor tasks with public datasets or coursework data where you can define a measurable outcome: classification (churn, fraud), regression (price forecasting), or causal inference (A/B test analysis). Define feature engineering (the process of transforming raw inputs into signals useful for models) early in the project plan and allocate time to validate features with simple baselines before reaching for complex models.

A practical first project is a small classification pipeline: predict customer churn or loan default from a tabular dataset. Start with exploratory data analysis (EDA, exploratory data analysis is the step where you summarize distributions and detect quality issues) in a notebook, then create a reproducible train/test split: from sklearn.model_selection import train_test_split; X_train, X_test, y_train, y_test = train_test_split(X, y, test_size=0.2, stratify=y). Evaluate with precision, recall, and area under the ROC curve rather than only accuracy; include a short notebook narrative that explains why you chose each metric and what business decision it informs.

For a second project, build a miniature ETL pipeline that moves data from SQL into a cleaned CSV and a simple model-serving script. Push heavy aggregations into the database using window functions and GROUP BY, then pull the reduced dataset into pandas for feature transforms. Containerize the pipeline with a minimal Dockerfile to lock dependencies and demonstrate reproducibility. This project highlights data engineering skills—SQL pushdown, idempotent transformations, and dependency management—which many entry roles expect and which separate toy notebooks from production-ready work.

A third project should focus on communication and interpretability: an interactive dashboard or a model-interpretability notebook that stakeholders can explore. Use Streamlit or a lightweight dashboard to let non-technical reviewers filter cohorts, inspect feature importances, and view model predictions on example records. Demonstrate interpretability techniques such as SHAP values or partial dependence plots and explain what model signals mean for the product. This kind of data science project shows you can translate technical results into actionable recommendations, not just scores and charts.

Sequence projects to show progression: start with one small supervised task, add a pipeline/engineering project, and finish with a communication-focused build. Keep each project in a GitHub repo with a clear README, concise notebooks, and scripts under src/ so reviewers can run your work without guessing environments—include a requirements.txt or conda environment and a reproducible run script. Aim to complete two to three polished portfolio projects during your first two years; after that, you’ll have concrete artifacts to discuss in interviews and a natural transition to the semester-by-semester roadmap that maps those projects to course milestones.

Internships Portfolio and Career Advancement Paths

Building on this foundation, prioritize internships and a tight portfolio as the two highest-leverage signals you can produce in your first two years: internships show you can operate inside a team and portfolio projects prove your technical depth and reproducibility. Recruiters and hiring managers look for demonstrable outcomes—models that moved a metric, ETL jobs that reduced latency, or an interactive dashboard used in decision meetings—so frame work around measurable impact. Keep the keywords you care about front and center in your artifacts: label repos with clear intent (example: churn-prediction-demo) and document the business question, data lineage, and evaluation metric. This makes your portfolio discoverable and your internships easier to translate into next steps for career advancement.

How do you turn an internship into a full-time offer and meaningful career growth? Start by owning a concrete slice of product or data work that has an observable metric: reduce daily pipeline failures, improve a model’s precision at the business threshold, or automate a recurring report. In practice that means defining a 30/60/90 plan with measurable milestones, instrumenting experiments (for example, compute precision and recall on a held-out test set rather than only reporting accuracy), and demoing incremental wins in biweekly syncs. Build on the technical patterns we covered earlier—extract with SQL, transform in pandas, and encapsulate reproducible experiments in a script or container—so your sponsor can see how an exploratory notebook becomes production-ready code.

Your portfolio should show progression and production-awareness, not more toy notebooks. Keep two to three polished portfolio projects that demonstrate end-to-end discipline: data extraction with a SQL query saved in src/data.sql, a feature engineering module under src/features.py, reproducible model training wrapped behind a train.sh or Dockerfile, and a README that explains how to run and validate results. Include small tests or scripts that reproduce key numbers (for example, a unit test that asserts that a cleaned dataset has no nulls in critical features) and add a short narrative that ties model metrics to business impact. These artifacts prove you understand observability, reproducibility, and deployment constraints—skills that turn internship experience into faster career progression.

Choose career paths deliberately and signal your direction through projects and coursework. If you want a product-facing data scientist role, prioritize causal-inference projects and A/B analysis; if you prefer ML engineering, emphasize pipelines, CI, and containerization; if you tilt toward data engineering, focus on ETL idempotency, schema design, and SQL pushdown. Parallel structure helps reviewers scan your resume: list role → primary signals → representative project (Data Scientist → A/B testing, interpretability → treatment-effect notebook). By the end of sophomore year, aim to have at least one artifact that maps directly to the role you want so interviewers see alignment between experience and job requirements.

Leverage internships for mentorship, referrals, and internal mobility rather than treating them as isolated gigs. Request regular technical feedback, ask to pair on code reviews, and volunteer to present a short demo to the product team that highlights trade-offs and uncertainty—this visibility creates advocates who can vouch for you. Track your measurable contributions (commits, reduced latency, improved KPI) and ask managers for a written summary you can include as a one-line impact in applications. Participate in team rituals—on-call rotations, retro write-ups, or sprint demos—so you learn operational responsibilities that distinguish junior hires from entry-level candidates.

As you prepare for interviews and next roles, orient your portfolio and internship stories around outcomes, reproducibility, and role-specific signals; doing so makes career advancement predictable rather than accidental. In the next section we’ll map these project types and internship goals into a semester-by-semester roadmap that helps you time coursework, project milestones, and application windows to maximize conversion into full-time opportunities.