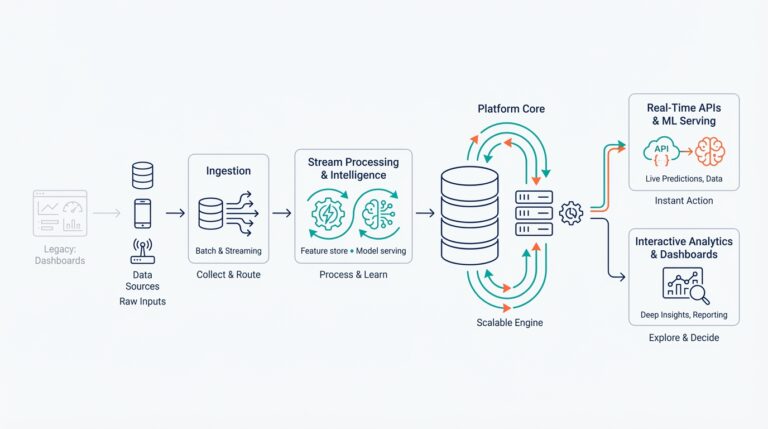

Choose database type and engine

Building on this foundation, the first technical decision you make—picking a database type and database engine—shapes schema flexibility, operational complexity, and cost for months or years. Choose carefully: the wrong database type locks you into query patterns that are expensive to change, and the wrong database engine can create bottlenecks you only notice under load. In the next few paragraphs we’ll weigh the trade-offs you face when you decide between relational and NoSQL approaches and when to favor managed engines over self-hosting.

Start with the data shape and access patterns rather than hype. If your data is highly relational, requires multi-row ACID transactions (atomicity, consistency, isolation, durability), or depends on complex joins and ad hoc SQL analysis, a relational database engine is usually the right fit. Conversely, if you expect schemaless documents, massive key-value lookups, or write-heavy telemetry ingestion, NoSQL engines often provide simpler horizontal scaling. How do you choose between relational and NoSQL engines for an early-stage product? Map expected queries, write/read ratio, and consistency requirements to concrete examples: payments need strong consistency and transactions; analytics pipelines tolerate eventual consistency.

When you opt for a relational engine, prefer ones with strong tooling, reliable replication, and mature migration ecosystems. Engines like PostgreSQL and MySQL (and their managed variants) give you expressive SQL, ACID guarantees, and robust indexing options; that matters when you run joins, window functions, or need foreign-key enforcement. For example, using Postgres lets you write a single transactional flow to debit an account and create an audit row with a straightforward two-statement transaction rather than implementing compensating logic across services. Plan for connection pooling early: application servers make many short-lived connections and Postgres’ connection limit will shape your deployment architecture.

If you pick a NoSQL engine, choose the model that matches your domain: document stores (for product catalogs and user profiles), key-value stores (for session caches and feature flags), wide-column stores (for time-series and event logs), or graph databases (for social graphs and recommendation engines). NoSQL engines like MongoDB, DynamoDB, Cassandra, and Redis trade relational feature completeness for scale and flexible schemas. That trade-off means you should design query patterns up front—secondary indexes and complex aggregations can become expensive or impossible without planning. Expect to embrace eventual consistency in many NoSQL systems and design idempotent write paths and reconciliation processes accordingly.

Operational characteristics of the database engine matter as much as data model fit. Managed services dramatically reduce operational burden—automated backups, patching, and multi-AZ failover let you focus on product work—but they introduce vendor cost and potential migration friction. Self-hosting gives fine-grained control and potentially lower cost at scale but increases staffing needs for backups, upgrades, monitoring, and disaster recovery. Consider scaling patterns: vertical scaling suits many relational engines early on, while horizontal sharding or partitioning becomes necessary as throughput grows. Also evaluate backup RPO/RTO, point-in-time recovery, and observability integrations when selecting an engine.

In practice, we often start with a single, well-supported database engine that matches our dominant access pattern and buy time to refine schema and partitioning. For example, use managed Postgres for apps that begin relational but may offload analytics to a columnar store later, or use a document store for a JSON-first product and build a small relational service for payment flows. Document your expected queries, failure modes, and migration path now so you don’t scramble later. Taking this approach prepares you to evolve the data platform without expensive rewrites and sets up the next step—schema design and partitioning decisions—with clarity and purpose.

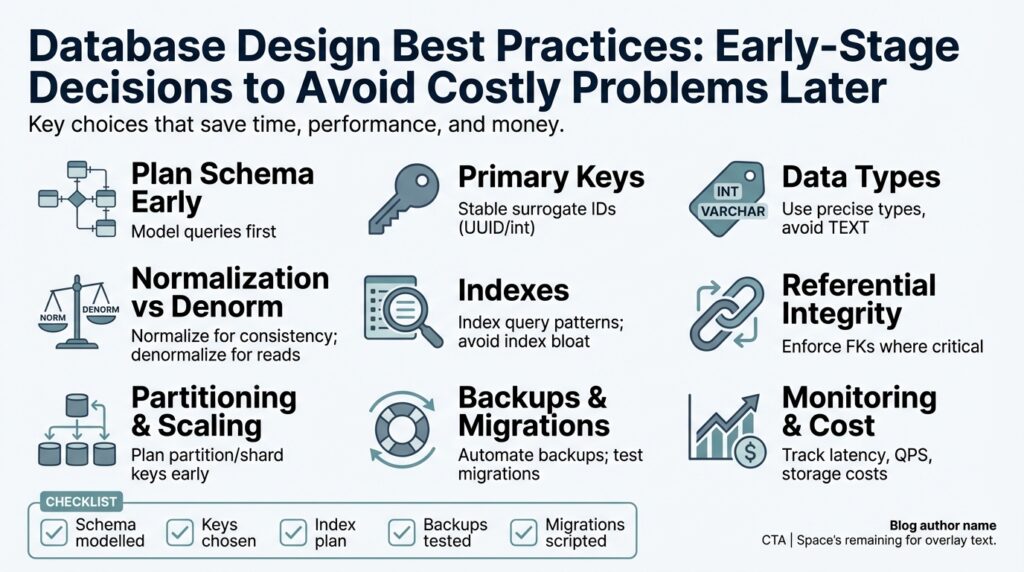

Model data and access patterns

Start by mapping your data model to the queries you actually expect to run—this is the highest-leverage step early on. If you can describe the most common reads and writes in a sentence each (for example: “fetch last 50 orders for a user” or “ingest 10k telemetry events per second”), you can make concrete schema and indexing choices that avoid expensive refactors. How do you balance normalization against read performance when latency matters? Answering that question up front forces you to prioritize indexing, denormalization, and query shapes rather than guessing based on hype.

Building on the database-type choices we discussed earlier, translate those expected query patterns into cardinalities, result-set sizes, and access frequency. List the dominant query patterns: point lookups, time-range scans, full-text searches, or multi-table joins, and capture metrics you’ll need later (rows returned, expected concurrency, write amplification). These metrics guide whether you design strong relational joins with FK constraints, a denormalized document that serves most reads, or a narrow key-value model for ultra-fast lookups. Knowing read/write ratio and consistency needs at this stage reduces migration friction as traffic grows.

Design schema decisions from the outside in: start with queries, then model tables or documents to satisfy them efficiently. If most queries filter by user_id and created_at, model a composite key around those columns instead of adding ad-hoc indexes later; create a composite index with CREATE INDEX ON events (user_id, created_at DESC) for efficient time-window queries. When you choose denormalization, document the duplication and the update path—either enforce invariants with transactions (if using a relational engine) or implement idempotent, eventually-consistent writes plus reconciliation jobs. This approach makes the trade-offs explicit and actionable.

Plan partitioning and key design to avoid hot keys and to support your scaling path. For time-series or append-mostly workloads, use time-based partitioning or sharding (monthly partitions, hourly buckets) so you can drop old data cheaply and keep writes distributed; for user-centric workloads, use a partition key that balances throughput (e.g., hash(user_id) or a tenant-aware composite key). In a key-value or wide-column model, a partition key plus sort key (PK=user#<id>, SK=event#<timestamp>) maps naturally to queries like “scan a user’s recent activity,” while also exposing predictable hotspots you can mitigate with salted prefixes or fan-out writes.

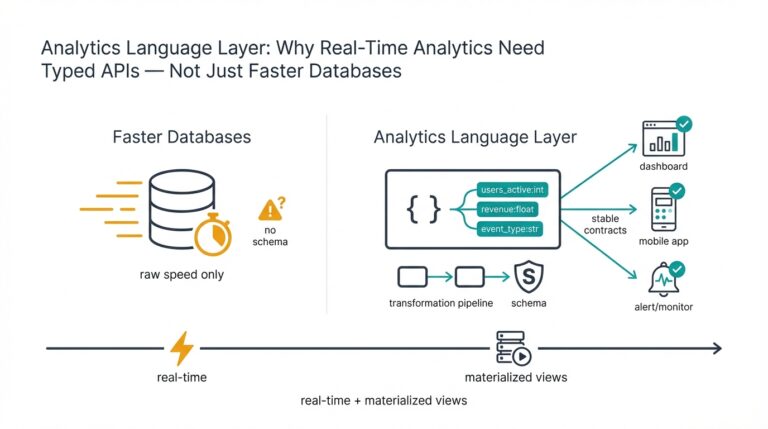

Don’t treat caching and read models as afterthoughts—design them alongside the primary model and access patterns. Use read replicas or materialized views for heavy analytic reads, and use application caches for hot, stable objects where eventual consistency is acceptable; always define the invalidation contract (time-to-live, write-through, or explicit invalidation) so you avoid stale-data surprises. If you expect high fan-out (notifications, feeds), consider a precomputed feed or a CQRS-style read store to move expensive joins off the critical write path and keep tail latency under control.

Finally, validate continuously: instrument slow queries, measure index usage, and run representative load tests that exercise your dominant query patterns. Capture real-world cardinality and latency data, then iterate on indexes, partitioning, and denormalization—treat the model as evolving, not perfect. Document the access patterns, the rationale behind each denormalization or index, and the expected operational implications so future engineers can extend the model without guessing; this prepares us to make the schema design and partitioning decisions that follow with confidence.

Define primary keys and types

Choosing the right primary key is one of the highest-leverage schema decisions you make early on because it shapes performance, sharding, and how safely you reference rows across services. Primary key design affects everything from index bloat to replication patterns, so treat this as an architectural choice—not an implementation detail. When should you pick a UUID over a sequential id? Asking that question up front forces you to evaluate collision domains, distributed ID generation, and physical write patterns before traffic exposes a problem.

Start by distinguishing natural keys from surrogate keys: a natural key is derived from business data (like an email or SKU) and a surrogate key is an artificial identifier the system generates. Natural keys can simplify uniqueness constraints, but they couple identity to mutable business attributes and can leak sensitive data into URLs or logs. Surrogate keys (integers, UUIDs) decouple identity from meaning and make joins and FK management predictable; we usually favor surrogates for long-lived tables that participate in many joins.

Surrogate implementations break down into sequential integers and globally-unique identifiers. Sequential ids (serial, identity) are compact and cache-friendly; they produce monotonically increasing clustered indexes in many relational engines which keeps inserts localized and reduces page splitting. UUIDs provide decentralized generation and are ideal for multi-service writes or offline clients, but their randomness can fragment clustered indexes and increase index size. In Postgres you can declare either pattern easily:

CREATE TABLE orders (

id BIGSERIAL PRIMARY KEY,

user_id UUID NOT NULL,

amount_cents INTEGER NOT NULL

);

-- or

CREATE TABLE events (

id UUID PRIMARY KEY DEFAULT gen_random_uuid(),

user_id UUID,

payload JSONB

);

Composite keys (multi-column primary keys) are useful when a natural access pattern is naturally composite—time-series rows keyed by (device_id, timestamp) or join tables keyed by (user_id, project_id). However, composite keys increase index width and complicate foreign-key references from other tables. When you need composite uniqueness for queries but also want a compact join target, prefer a single-column surrogate PK plus a unique composite index; this keeps joins cheap while preserving query semantics.

Consider how your primary key choice interacts with partitioning and sharding. In key-value and wide-column systems, a partition key determines data locality and hotspot behavior—design it around expected fan-out. For example, DynamoDB-style patterns use a partition key plus sort key (PK=user#

Remember that the primary key usually drives the clustered index and thus affects insert and query latency. In OLTP workloads where low tail latency matters, a compact, monotonically increasing key reduces fragmentation and improves cache locality. If you need distributed ID generation, evaluate time-based UUIDs or Snowflake-style monotonic IDs to get the benefits of decentralization without the full cost of random UUIDs. Weigh index size, FK storage overhead, and generation complexity when making a decision.

Practically, pick a pragmatic default and document it. For many early-stage teams we recommend a single-column surrogate primary key (BIGINT identity for relational OLTP or UUID with a documented generation strategy when writes are distributed). Capture why you chose it, how to migrate if needs change, and any invariants consumers rely on. This makes the primary key a deliberate choice you can evolve rather than a surprise during a traffic spike, and it sets up the next design step: indexing and partitioning strategies that align with your key and access patterns.

Balance normalization and denormalization

Building on this foundation, one of the practical trade-offs you’ll face is choosing how much to normalize your tables vs. when to denormalize for performance. The tension is simple: normalization reduces redundancy and enforces invariants, while denormalization reduces runtime joins and tail latency for reads. How do you decide when to duplicate a column or accept the complexity of maintaining derived data? Frame the decision by mapping real query patterns, read/write ratios, and acceptable staleness windows before you change the schema.

Normalization protects you from update anomalies and keeps storage and index size predictable, which matters when you run transactional workflows across multiple tables. When you normalize, foreign keys and third-normal-form design let you enforce integrity inside the database, simplify migrations, and make joins explicit—advantages for transactional consistency and auditability. Use normalization where writes are frequent, business rules change often, or the data model is authoritative (payments, ledgers, user identity). This predictable structure also makes schema design and partitioning easier to reason about as traffic grows.

Denormalization pays for itself when read latency or complex joins are the primary bottleneck and data can tolerate short windows of inconsistency. Precomputing aggregates, duplicating a small set of frequently-read columns, or storing a fully-formed document for a UI call can reduce multi-table joins and remove brittle join-paths in your application. The trade-offs are increased storage, more complex update paths, and potential for stale reads; therefore choose denormalization where it solves concrete latency requirements, like serving product catalogs, feeds, or dashboard queries that run on the request path.

Make the strategy concrete by treating denormalization as a controlled engineering pattern rather than an ad-hoc shortcut. Identify a small set of hot queries and duplicate only the columns those queries actually need; document each duplicate’s source of truth and the update contract. For relational engines you can keep invariants with transactional writes: for example, update the canonical row and its denormalized copy in the same transaction so readers never see half-baked state.

BEGIN;

UPDATE users SET name = 'A. Ramos' WHERE id = 123;

UPDATE orders SET user_name = 'A. Ramos' WHERE user_id = 123;

COMMIT;

When transactional updates aren’t feasible because of cross-service boundaries or scale, implement asynchronous, idempotent reconciliation: publish change events, apply them to read models, and run periodic fix-up jobs that validate the duplication. Combine materialized views, read replicas, and application caches with clear invalidation rules (TTL, write-through, or explicit invalidation) so your observability can detect drift and measure stale-rate. This keeps denormalization auditable and recoverable.

Operational practices matter as much as the initial schema design: add metrics for update lag, reconciliation failures, and how often denormalized reads return stale values. Test the full update path under load—both transactional and asynchronous—to reveal contention, hot keys, or excessive write amplification before traffic grows. Document why each denormalized field exists, its allowed staleness, and the rollback/migration plan so future engineers can safely refactor.

These decisions shape downstream choices like primary-key design, partitioning, and indexing, so treat them as part of the same architecture conversation. By selectively denormalizing hot-read paths, protecting core invariants with normalization, and instrumenting for drift, we get predictable performance without sacrificing maintainability. Next, we’ll apply these trade-offs to indexing and partitioning so the schema supports both efficient queries and scalable operations.

Design effective indexing strategy

Building on this foundation, an explicit indexing strategy is one of the highest-leverage optimizations you can make early—good indexes reduce latency and CPU cost, while bad ones create write amplification and maintenance debt. When you decide which indexes to create, treat indexing as part of the query design: map dominant query predicates, sorts, and join columns to concrete index choices rather than adding indexes reactively. Indexes are not free; they consume storage, slow writes, and increase complexity for migrations, so plan deliberately to avoid surprising operational costs later.

Start by asking a simple operational question: How do you decide which columns to index? The short answer is: index the columns that appear in WHERE, JOIN, and ORDER BY clauses for your hot paths, prioritizing high-selectivity filters and operations that determine result ordering. Selectivity—the fraction of rows a predicate matches—matters because an index on a low-selectivity column (like a boolean flag) rarely beats a sequential or bitmap scan. Use cardinality and expected result-set size from your access-pattern mapping to rank index candidates and limit the total number of indexes per table.

Different index types suit different query shapes; know their trade-offs. B-tree indexes are the default for equality and range queries and are generally the most efficient for OLTP workloads. GIN (Generalized Inverted Index) and GiST (Generalized Search Tree) support full-text search, array containment, and complex geometric lookups but use more space and have slower updates. Hash and specialized indexes can accelerate point-lookup patterns in niche cases but often lack ordering semantics. When you choose an index type, document why it matches the query pattern so future engineers can evaluate removal or replacement confidently.

Composite and covering indexes reduce lookup hops when ordered and constructed correctly. Create composite indexes with the most selective or most commonly filtered column first when queries filter on multiple fields, and include ordering columns if queries sort the same way. In Postgres you can create a covering index with INCLUDE to store columns used only by the SELECT list, for example: CREATE INDEX idx_orders_status_created_at ON orders (status, created_at DESC) INCLUDE (amount_cents); This keeps reads index-only and avoids an extra heap fetch, but remember that bigger index entries inflate memory and I/O costs on writes.

Leverage partial and expression indexes to keep index bloat down and capture specific access patterns. Partial indexes restrict indexing to rows matching a predicate (for example, WHERE deleted = false) which is perfect when most queries ignore soft-deleted rows. Expression or functional indexes let you index computed values—lower(email) or a JSONB path—so you can accelerate case-insensitive lookups or queries against nested fields without adding redundant columns. For text-heavy search requirements, evaluate a tsvector-based index or a dedicated search engine; avoid shoehorning full-text into a generic index unless you measure acceptable latency.

Operational discipline finishes the strategy: instrument and iterate. Use EXPLAIN ANALYZE to verify the planner chooses your index under realistic binds, track index usage with catalog views (for example, Postgres’ pg_stat_user_indexes), and measure write amplification and index bloat with regular monitoring. Schedule maintenance—vacuuming, reindexing, and partition trimming—based on observed churn, not guesswork. Weigh read-replica or materialized-view strategies against more indexes when tail latency matters: sometimes moving heavy analytic queries off the primary copy is cheaper than adding multiple wide indexes. Taken together, these practices let us align indexing choices with key distribution, access patterns, and scaling plans so indexes remain an asset rather than a liability as the system grows.

Plan schema migrations and scaling

Building on this foundation, a migration plan that anticipates growth prevents frantic, high-risk changes when traffic spikes. Schema migrations and scaling are operational events, not one-off developer tasks, so treat them as product launches: coordinate deploy windows, define success criteria, and instrument rollbacks before you touch production. Early decisions—how you add columns, how you partition hot tables, and how you design your shard key—determine whether a migration is a brief maintenance window or a week-long outage. How do you perform zero-downtime schema migrations while keeping latency and risk low?

Start with the expand-contract pattern for schema changes: expand the schema in a backward-compatible way, migrate data, then contract once all callers use the new shape. For example, add nullable columns or new indexes without replacing existing code, run a controlled backfill in chunks, switch reads to the new column, and only then make the column NOT NULL and drop the old field. Use SQL like the following as a safe sequence for small tables:

ALTER TABLE orders ADD COLUMN user_name_new TEXT;

-- backfill in small transactions

UPDATE orders SET user_name_new = user_name WHERE user_name_new IS NULL LIMIT 10000;

ALTER TABLE orders ALTER COLUMN user_name_new SET NOT NULL;

ALTER TABLE orders DROP COLUMN user_name;

For large tables and high-throughput systems, avoid long locks: prefer online schema-change tools or shadow-table techniques that copy data incrementally and then atomically swap names. Tools such as gh-ost or pt-online-schema-change implement chunked copying and throttling to minimize impact; alternatively, create a new table with the desired schema, copy rows in chunks while applying ongoing write diffs, and finally perform a fast rename inside a short transaction. This pattern also supports backwards-compatibility because you can route a fraction of reads to the new table for canary verification before flipping all traffic.

Scaling often forces architectural migrations that are more invasive than adding a column—resharding, partitioning, or moving to a different engine require premeditated strategies. When you plan sharding or partitioning changes, design your shard/partition key and version it in application logic so you can route traffic during resharding. Range-based partitions are intuitive for time-series workloads, while hash-based sharding reduces hotspots for user-centric traffic; whichever you pick, document the operational path to split or merge shards and the impact on cross-shard transactions and joins.

When the migration includes data reorganization rather than only schema, prefer event-driven and CDC-based approaches to keep systems synchronized. Capture a snapshot, start CDC (change-data-capture) streaming into the new schema or service, replay the snapshot into the target, and then apply the CDC stream until lag is zero—this minimizes downtime and avoids dual-write inconsistencies. Make all migration writes idempotent, implement retry-safe chunks for backfills, and provide reconciliation jobs that compare row counts, checksums, and sampled rows. Instrument replication lag, per-table throughput, and error rates so you can abort or throttle the process quickly if hotspots appear.

Operational discipline separates a brittle migration from a reliable one: maintain a migration log table with version, status, owner, and rollback steps; gate schema toggles behind feature flags and canary traffic; run rehearsals in production-like environments; and always take verified backups with tested restores before large migrations. Define observable SLOs for migration success (latency, error rate, replication lag) and automate alerts when those thresholds are crossed. These practices let us evolve schema and scaling in a controlled way and prepare the team for whatever comes next in the data platform.