Prerequisites and environment

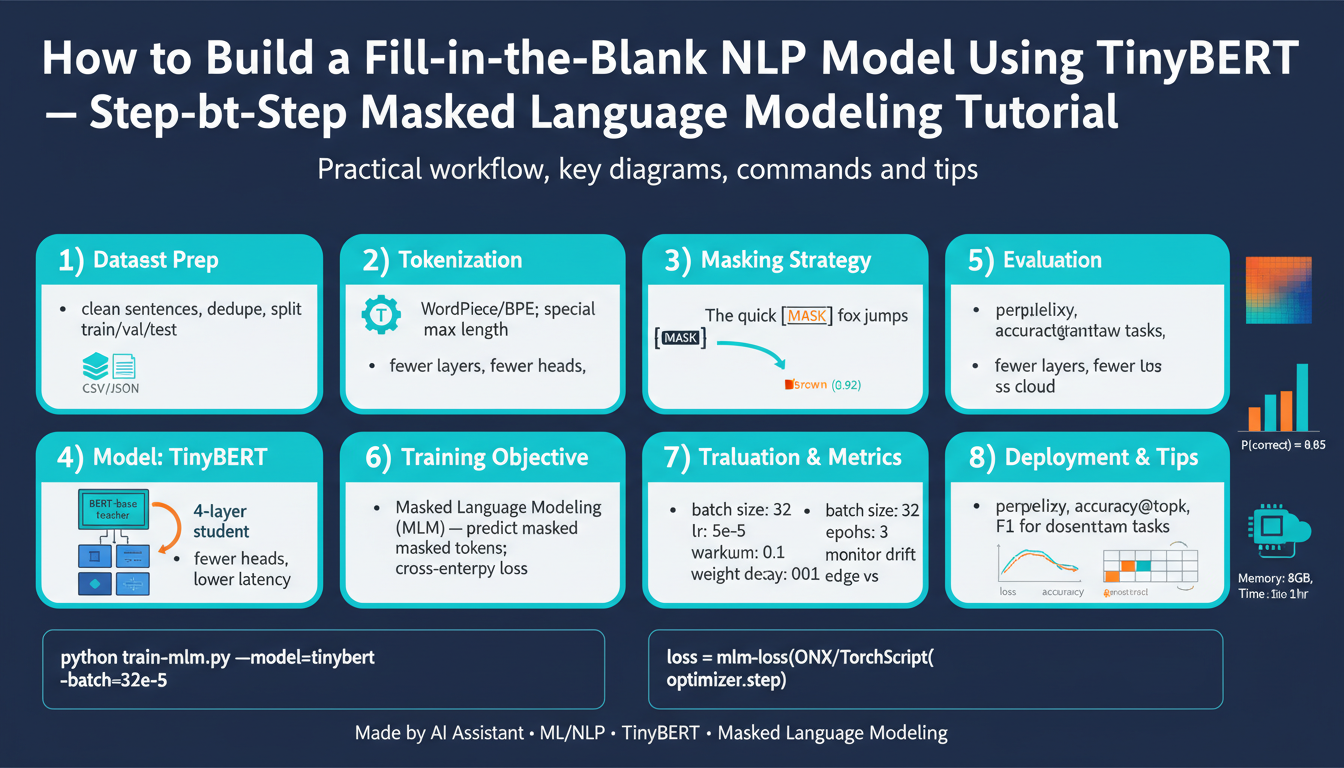

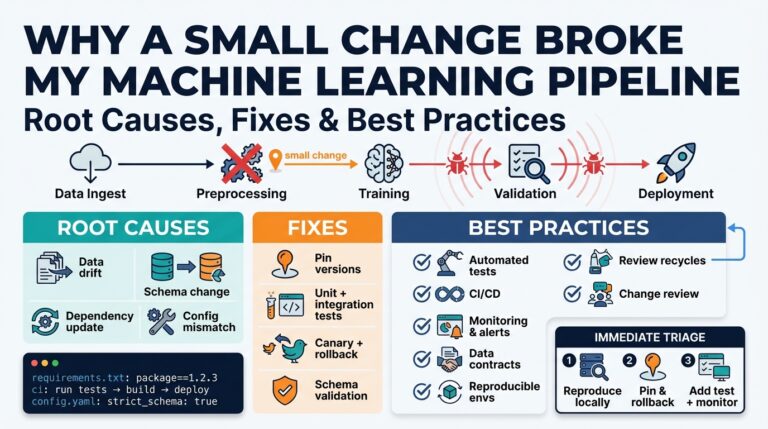

Building on the concepts we introduced earlier, you should arrive here with the goal of training a TinyBERT-based masked language model for fill-in-the-blank NLP tasks, so the environment must be predictable, reproducible, and GPU-capable. Start by deciding whether you’ll finetune on a workstation, a cloud GPU, or inside a container orchestration system; this choice drives the rest of the setup because TinyBERT training benefits from accelerated linear algebra and stable mixed-precision. We’ll assume you want to run realistic experiments (checkpointing, mixed precision, experiment tracking) rather than quick local proofs-of-concept, and we’ll show practical configuration patterns that match that intent. TinyBERT and masked language modeling workflows reward consistency: the same Python, CUDA, and library builds across runs reduce noisy results and failed runs.

The most important hardware consideration is GPU availability and memory footprint because masked language modeling uses large batches of tokenized contexts and teacher-student or distillation steps can double memory use. Ask yourself: how large are your sequences and batch sizes, and can your GPU(s) hold the TinyBERT student plus optimizer state? For modest sequence lengths (128 tokens) a 16–24GB GPU can train small batches; for 512-token contexts or mixed teacher-student distillation you’ll need multiple GPUs or gradient accumulation to simulate larger batches. Use mixed precision (FP16) to reduce memory pressure and accelerate throughput, and reserve a CPU-only fallback plan for preprocessing and tokenization tasks.

Software dependencies must match your compute choice and be pinned to deterministic versions. Use Python 3.8+ and install a PyTorch build compatible with your CUDA driver; mismatched CUDA and PyTorch versions are the most common runtime failure. We recommend installing the Hugging Face Transformers and Datasets libraries for model, tokenizer, and data pipelines, plus the tokenizers package for fast tokenization and an orchestration tool such as Accelerate for multi-GPU runs. A minimal pip set of commands you can adapt is:

python -m venv .env && source .env/bin/activate

pip install "torch" "transformers" "datasets" "tokenizers" "accelerate"

Adjust the torch wheel to match your CUDA version when needed.

Manage the environment with containers or virtual environments so experiments are reproducible and shareable. Using conda or venv keeps Python-level isolation, while a Docker image with an NVIDIA base (CUDA + cuDNN) gives portability between cloud and on-premise GPUs; this also simplifies CI pipeline integration and deployment of evaluation jobs. Containerize your training entrypoint and mount data volumes for corpora and checkpoints; tag images with explicit versions of Python, CUDA, and library requirements to avoid “works-on-my-machine” regressions. We also recommend checking in an environment YAML or requirements.txt alongside an example train config to speed onboarding for other engineers.

You’ll need curated text corpora and tokenizer configuration aligned with TinyBERT’s pretraining tokenizer. For masked language modeling we use the BERT-style mask token ([MASK]) and the same WordPiece or BPE tokenizer scheme used by the original TinyBERT checkpoint; mismatched tokenizers alter vocabulary indices and break the model. Prepare datasets with the Hugging Face Datasets library, create masked examples on-the-fly (mask 15% of tokens, with the 80/10/10 replace/keep/random distribution typical for BERT), and validate tokenization by printing token ids and detokenized outputs. For example, tokenization and a mask example might look like:

from transformers import AutoTokenizer

tokenizer = AutoTokenizer.from_pretrained("path-or-name-of-tinybert-tokenizer")

inputs = tokenizer("The quick brown fox jumps over the lazy dog", return_tensors="pt")

# Apply masking logic to inputs['input_ids'] before feeding to the model

Finally, configure training hyperparameters, logging, and checkpoint strategies before you start long runs. Choose sensible defaults for learning rate, weight decay, and batch accumulation when you first run experiments, enable mixed-precision to speed throughput, and set deterministic seeds for reproducibility. Enable incremental checkpointing and lightweight experiment tracking (e.g., a CSV logger or a minimal ML tracking tool) so we can compare masked language modeling losses and fill-in-the-blank accuracy across runs. With this environment in place, we can move directly into dataset engineering and the TinyBERT fine-tuning recipe in the next section.

Install libraries and tools

Getting the libraries and tools right is the single most common source of friction when you move from a toy masked language modeling experiment to reproducible TinyBERT training. If your Python, CUDA, or library builds are inconsistent across machines you’ll waste hours diagnosing runtime errors or subtle numerical differences, so we’ll make the install steps explicit and verifiable. Building on the environment guidance above, this section gives concrete commands and sanity checks so you can install the stack that reliably runs TinyBERT fine-tuning jobs at scale.

Start by creating an isolated Python environment so dependencies don’t collide with other projects. Use venv for lightweight isolation or conda when you need system-level package control; for venv run:

python -m venv .env && source .env/bin/activate

python -m pip install --upgrade pip setuptools wheel

If you prefer conda:

conda create -n tinybert python=3.10 -y

conda activate tinybert

These steps let you pin specific versions for reproducibility and make containerizing simpler later.

How do you ensure your CUDA and PyTorch versions match? Verify your GPU driver and runtime first: run nvidia-smi on the host to confirm driver compatibility and CUDA runtime availability. Inside Python, confirm the CUDA-aware PyTorch build with a quick check:

import torch

print(torch.__version__)

print(torch.cuda.is_available())

print(torch.version.cuda) # shows the CUDA runtime the wheel was built against

If torch.cuda.is_available() is False, re-check your wheel selection or driver install before proceeding; mismatched CUDA/PyTorch is the most frequent blocker for training TinyBERT models on GPU.

Next, install the core Python libraries you’ll use for masked language modeling, tokenizer handling, and dataset pipelines. Pick the PyTorch wheel that matches your CUDA runtime (replace cuXXX with the correct CUDA tag or use the CPU wheel if necessary). Install the rest with pinned or minimally constrained versions to keep runs deterministic:

# Example: select the torch wheel that matches your CUDA runtime, then:

pip install "torch==<pick-matching-wheel>" # choose wheel for cu118/cu121/etc.

pip install "transformers==<compatible-version>" datasets tokenizers accelerate

# Optional for optimization: pip install bitsandbytes safetensors

Include “Hugging Face Transformers” and tokenizers in these installs so your tokenizer, model config, and I/O behave consistently; mismatched tokenizers break fill-in-the-blank training fast.

If you use containers for portability, start from an NVIDIA CUDA base image and pin the OS and CUDA tags. A minimal Dockerfile skeleton looks like this (replace placeholders):

FROM nvidia/cuda:<CUDA_TAG>-cudnn-ubuntu22.04

RUN apt-get update && apt-get install -y python3 python3-venv python3-pip git

COPY requirements.txt /workspace/

RUN pip install -r /workspace/requirements.txt

WORKDIR /workspace

Mount your datasets and checkpoints as volumes at runtime and run the container with the NVIDIA container runtime so GPUs are exposed.

Configure Accelerate for multi-GPU or multi-node runs to avoid writing distributed boilerplate. Initialize a minimal config interactively with:

accelerate config

# later: accelerate launch train.py --config_file accelerate_config.yaml

This enables mixed-precision (FP16) and distributed strategies that are crucial for training TinyBERT efficiently on multiple GPUs.

Finally, validate the installation with a small sanity test that loads the TinyBERT tokenizer and a TinyBERT masked LM checkpoint and runs a forward pass on the GPU. That confirms your Hugging Face Transformers model, tokenizer, and PyTorch/CUDA stack are aligned:

from transformers import AutoTokenizer, AutoModelForMaskedLM

tokenizer = AutoTokenizer.from_pretrained("path-or-name-of-tinybert-tokenizer")

model = AutoModelForMaskedLM.from_pretrained("path-or-name-of-tinybert")

inputs = tokenizer("The quick brown [MASK] jumps.", return_tensors="pt").to(model.device)

outputs = model(**inputs)

print(outputs.logits.shape)

Run this check before you start long masked language modeling experiments so you catch tokenization mismatches early. Taking these steps ensures your tooling, CUDA, and library versions are reproducible across local workstations, cloud GPUs, and containerized CI, which keeps your TinyBERT training stable and lets you move on to dataset engineering and fine-tuning without avoidable runtime surprises.

Prepare dataset and masks

Building on this foundation, the first practical task is transforming raw corpora into a training-ready TinyBERT dataset that embeds correct tokenization and robust mask patterns for masked language modeling. We want reproducible, inspectable samples so you can reason about how token boundaries, special tokens, and multi-token targets affect fill-in-the-blank quality. How do you ensure masks align with WordPiece tokenization and multi-token answers? The next paragraphs show concrete practices, checks, and an example collator you can adopt.

Start by curating and normalizing your text corpus before tokenization. Remove low-value boilerplate (HTML, logs), deduplicate near-duplicates, and inspect length distributions so sequence lengths match your GPU memory plans; this avoids truncated targets during training. Normalize unicode and whitespace consistently to prevent the tokenizer from producing unexpected subword splits; inconsistent normalization creates mismatched token ids that silently break training. Keep a small validation split of representative documents to measure fill-in-the-blank accuracy later.

Always use the same tokenizer instance that the TinyBERT checkpoint expects; mismatched tokenizers change vocab indices and invalidate pretrained weights. Load the tokenizer with AutoTokenizer.from_pretrained(“…”) and assert special token ids (pad_token_id, mask_token_id, cls_token_id, sep_token_id) match your model config. Print tokenized examples and detokenized reconstructions to validate round-trips: if detokenization changes text meaning, adjust normalization or tokenizer settings before masking and batching.

Choose a masking strategy that reflects the downstream fill-in-the-blank task rather than copying defaults blindly. Dynamic masking (apply masks on-the-fly every batch) gives more varied supervision than static pre-masking and reduces disk usage; for typical BERT-style setups we still sample ~15% of tokens with an 80/10/10 replace/keep/random scheme, but for fill-in-the-blank you may prefer span masking (contiguous token spans) or whole-word masking so multi-token answers remain intact. When building labels, set non-masked token targets to -100 so PyTorch’s CrossEntropyLoss ignores them; e.g.:

# pseudo-collate logic

labels = input_ids.clone()

mask_positions = sample_mask_positions(input_ids, prob=0.15, whole_word=True)

labels[~mask_positions] = -100

# apply 80/10/10 replacement on input_ids at mask_positions

Implement a collate function that handles padding, attention masks, and dynamic masks consistently. Either extend Hugging Face’s DataCollatorForLanguageModeling or write a custom collator that receives a list of tokenized examples, pads to the batch max length, computes attention_mask, and produces labels with -100 on non-masked positions. This collator is the single source of truth for masking behavior; keeping masking in-memory during collation preserves randomness and avoids heavy I/O for pre-masked datasets. Also ensure your collator returns an explicit pad_token_id so the model’s embedding lookup and loss masking remain correct.

Handle long documents with deterministic chunking and optional sliding windows so you don’t lose cross-sentence contexts needed for realistic blanks. Chunk long sequences into fixed-length examples with a configurable stride to create overlapping contexts; this preserves continuity for answers that straddle chunk boundaries. For evaluation and qualitative inspection, maintain a mapping from example index back to original text and token offsets so you can present model predictions in the original text frame.

Validate the prepared dataset with automated checks and a small forward pass. Sample 100 masked examples, print token ids, masked input strings, and label token ids to confirm expected coverage and that multi-token spans were masked atomically if you chose whole-word/span masking. Compute mask coverage statistics (mean and variance of masked token count per sample) and run a single batch through the model to confirm logits.shape == (batch, seq_len, vocab_size). Set deterministic seeds in data loaders to reproduce failing examples during debugging.

Persist and version your processed dataset artifacts for reproducibility and experiment comparison. Save tokenized datasets with datasets.Dataset.save_to_disk or export deterministic sharded TFRecords/Arrow files if you use streaming; always record tokenizer checksum, mask-config parameters (percent, span distribution, whole-word flag), and a small sample manifest for human inspection. With these artifacts in place and validated, we can move directly into building the training loop and monitoring fill-in-the-blank accuracy on the held-out validation set.

Tokenize and apply masking

Masked language modeling and correct tokenization are the foundation of reliable fill-in-the-blank training, so we start by treating tokenization and masking as a single, testable contract rather than two separate concerns. Begin by choosing the exact TinyBERT tokenizer instance you’ll use for training and inference, then pin that choice in your dataset metadata so experiments remain reproducible. Front-load your preprocessing to assert special token ids (pad, mask, cls, sep) and to confirm detokenized samples round-trip precisely; these quick checks catch the vast majority of subtle vocabulary and normalization mismatches early.

Building on this foundation, validate tokenizer behavior against realistic sentences and edge cases before you apply any masks. Use examples that include punctuation, contractions, and domain-specific tokens so you can see how subword splits behave in your corpus; print token ids, subword pieces, and reconstructed text to verify correctness. If your application targets technical content or code snippets, include those in the sanity set because tokenization of symbols and identifiers often creates multi-token targets we must treat atomically.

When designing masking, choose a strategy that matches downstream evaluation: dynamic masking for data efficiency and variation, span or whole-word masking when multi-token answers are common. How do you ensure masks align with subword boundaries? Sample mask positions at the word level (using the tokenizer’s word/offset mapping) or combine subword-aware heuristics so you don’t accidentally mask half of a multi-token token that represents a single semantic unit. Use an 80/10/10 replacement/keep/random distribution for BERT-style supervision, but prefer span masking for long named entities or programming identifiers that must be predicted as a contiguous sequence.

Implement a single collate function as the canonical source of masking logic and batch construction so all downstream steps see the same behavior. The collator should pad inputs, compute attention_mask, sample mask positions per example, create labels with -100 on non-masked tokens, and apply the 80/10/10 replacement policy on input_ids. For clarity, here’s the core label step you can mirror in your collator:

labels = input_ids.clone()

mask_pos = sample_mask_positions(input_ids, prob=0.15, whole_word=True)

labels[~mask_pos] = -100 # ignore in loss

# Then apply 80/10/10 to input_ids at mask_pos

Treat multi-token answers and long documents deliberately: prefer whole-word or span masking and use a sliding-window chunker with stride when sequences exceed your training length. Keep a mapping from token indices back to original character offsets so you can present model predictions in the original text for qualitative evaluation; this mapping makes it trivial to show predicted fills in context rather than as detached token ids. During validation, sample examples where spans were masked atomically and ensure the model’s top-k predictions reconstruct plausible surface forms—this is the real litmus test for fill-in-the-blank performance.

Operational details matter: ensure padded batches use the tokenizer’s pad_token_id and that label dtype is torch.long with ignored positions set to -100 so CrossEntropyLoss behaves as expected. Return explicit attention_mask and, when using mixed precision or device placement, move all tensors to the same device in the collator or immediately after batching to avoid subtle CPU/GPU mismatches. Keep masking deterministic under a reproducible seed for debugging runs, but randomize masks for final training to maximize sample diversity and generalization.

With masking implemented in a single, inspectable collator and tokenization validated on representative edge cases, you’re ready to feed consistent batches into the TinyBERT training loop. The next step is to wire this collator into your dataloader and experiment harness, monitor per-batch mask coverage statistics, and run short debug jobs that print masked inputs, labels, and top model predictions so we can iterate on mask heuristics before long runs.

Load TinyBERT and tokenizer

Loading a pretrained TinyBERT and the matching tokenizer is the single most critical step before you start masked language modeling or any fill-in-the-blank training, because any mismatch between model weights and vocabulary will silently break training. You want the tokenizer, special token IDs (pad, mask, cls, sep) and model config to be exactly the same contract used during TinyBERT pretraining; if they aren’t aligned your loss, logits indexing, and detokenization checks will be meaningless. This is why we always validate round-trip tokenization and inspect special token ids before building dataloaders or collators.

Building on this foundation, load the tokenizer and model using Hugging Face’s Auto classes and wire device placement explicitly so you don’t discover CUDA/PyTorch mismatches mid-run. Use AutoTokenizer.from_pretrained for the tokenizer and AutoModelForMaskedLM.from_pretrained for the TinyBERT checkpoint, then move the model to your GPU (or use accelerate/device_map for multi-GPU). For reproducibility, pass local paths or a pinned model name and pin cache_dir when running on ephemeral CI. Example minimal pattern to mirror in your training scripts:

from transformers import AutoTokenizer, AutoModelForMaskedLM

import torch

tokenizer = AutoTokenizer.from_pretrained("path-or-name-of-tinybert-tokenizer", use_fast=True)

model = AutoModelForMaskedLM.from_pretrained("path-or-name-of-tinybert")

model.to(torch.device("cuda" if torch.cuda.is_available() else "cpu"))

How do you ensure the tokenizer matches the model’s vocabulary and special tokens? After loading, explicitly assert that tokenizer.pad_token_id, tokenizer.mask_token_id, and tokenizer.cls_token_id equal the values in model.config (or at least are present and not None). Print a few tokenized examples and detokenized outputs, including edge cases from your corpus, to validate normalization and subword boundaries. If detokenization changes wording or token splits consistently, adjust tokenizer normalization settings or replace the tokenizer with the exact checkpoint-provided tokenizer rather than guessing based on name.

Tokenizers have runtime options that materially affect masked language modeling. Prefer fast tokenizers (Rust-based) for performance, but confirm they expose offsets and word mapping if you rely on whole-word or span masking. If your corpus contains code, identifiers, or domain-specific tokens, test those cases specifically and consider adding new tokens with tokenizer.add_tokens and then calling model.resize_token_embeddings(len(tokenizer)). This step preserves pretrained weights while safely extending the vocabulary, but remember to initialize new token embeddings appropriately and monitor early-training loss for embedding instability.

Practical loader tips you’ll appreciate during long runs: pin the tokenizer to the dataset metadata (save tokenizer.json or tokenizer.save_pretrained in your experiment artifacts) and load from that exact path during evaluation and inference. When running multi-GPU or multi-node experiments, either call model.to(device) after wrapping with accelerate or let accelerate handle device placement via accelerate launch; avoid moving tokenizers between devices—tokenizers live on CPU. Also ensure your collator reads tokenizer.mask_token_id and tokenizer.pad_token_id directly so that mask creation and padding are consistent across training and validation.

Finally, instrument simple sanity checks immediately after loading so you catch mismatches early: confirm logits shape equals (batch, seq_len, vocab_size) on a synthetic batch, verify that labels use -100 for non-masked positions, and run a small masked inference to print top-k token predictions detokenized into readable strings. These checks bridge model loading and dataset/tokenization readiness and make the downstream masked language modeling training deterministic and debuggable. With the model and tokenizer validated and cached, we can wire the collator and masking logic into your dataloader and start short debug runs to iterate on mask heuristics before long fine-tuning jobs.

Train, evaluate, and infer

Building on this foundation, the first thing to decide is how you will orchestrate the training loop so it matches your reproducible environment and collator behavior for TinyBERT masked language modeling. Start each run by loading the collator and tokenizer you validated earlier, pinning seeds, and confirming special token ids; if those contracts change mid-run your logits-to-text pipeline will break silently. Choose an optimizer (AdamW) with a small base learning rate (e.g., 1e-5–5e-5 for fine-tuning), enable mixed precision to reduce memory pressure, and plan gradient accumulation when your GPU cannot hold desired effective batch sizes. How do you schedule validation? Run a lightweight validation every N steps that balances iteration speed with quick signal for overfitting.

Implement a concise, observable training loop where checkpointing and logging are first-class citizens so you can recover and compare experiments reliably. Save model.state_dict(), optimizer and scheduler state, and the tokenizer snapshot at each meaningful improvement; prefer incremental checkpointing (every epoch or every X steps) plus a best-checkpoint policy based on a validation metric. Use a cosine or linear warmup scheduler to stabilize early steps, and monitor mask-coverage statistics from the collator so you know your dynamic masking is behaving as expected. For reproducibility, log the mask-config (percent, span/whole-word) with each checkpoint so post-hoc comparisons are valid.

Evaluation must measure both language modeling fit and real fill-in-the-blank utility, not just loss. Compute validation loss and perplexity as basic signals, but also report top-k accuracy at masked positions (top-1, top-5) and span-level exact match when you use span or whole-word masking. For multi-token targets, aggregate predictions by detokenizing the top-k token sequences (or constrained beam search for spans) and compare to gold text; use a relaxed F1 for partial credit on long entities. Run deterministic validation masks for consistent numeric comparison, then complement those runs with randomized masks to estimate generalization under variable blanks.

When you move to inference, convert the masked positions back to readable fills and handle subword joins carefully to avoid corrupted outputs. Use model outputs.logits to select top-k token ids at mask positions and then call tokenizer.decode with clean_up_tokenization_spaces=True and skip_special_tokens=True; for multi-token spans, either perform constrained decoding that enforces contiguity or generate with a small beam to preserve plausible sequences. If your downstream needs interactive query-style fill-in-the-blank (user-provided masked sentence), batch those requests and colocate tokenization on CPU while moving tensors to GPU in large batches to maximize throughput without blocking the web thread.

Operationally, guard against common failure modes during fine-tuning and inference: catastrophic forgetting, embedding drift when you add new tokens, and misaligned tokenizer/model contracts. Use a small held-out validation set that mirrors your production blanks for early stopping, and compare to a frozen TinyBERT baseline to ensure fine-tuning yields real gains on fill-in-the-blank accuracy. If you distill from a larger teacher, track both student loss and distillation loss terms separately so you can tune trade-offs between fidelity and compactness. Finally, test inference behavior on edge cases—URLs, code identifiers, hyphenated names—because tokenizer quirks are the most frequent source of poor surfaced predictions.

Taking these steps together gives you a repeatable loop: train with robust checkpointing and mixed precision, evaluate with both token- and span-aware metrics, and infer with deterministic detokenization and span-aware decoding. In the next section we’ll wire the best checkpoint into a small server-side inference harness and show how to expose a constrained fill-in-the-blank API that preserves tokenizer contracts and supports batched requests.