Why Use PostgreSQL Schemas

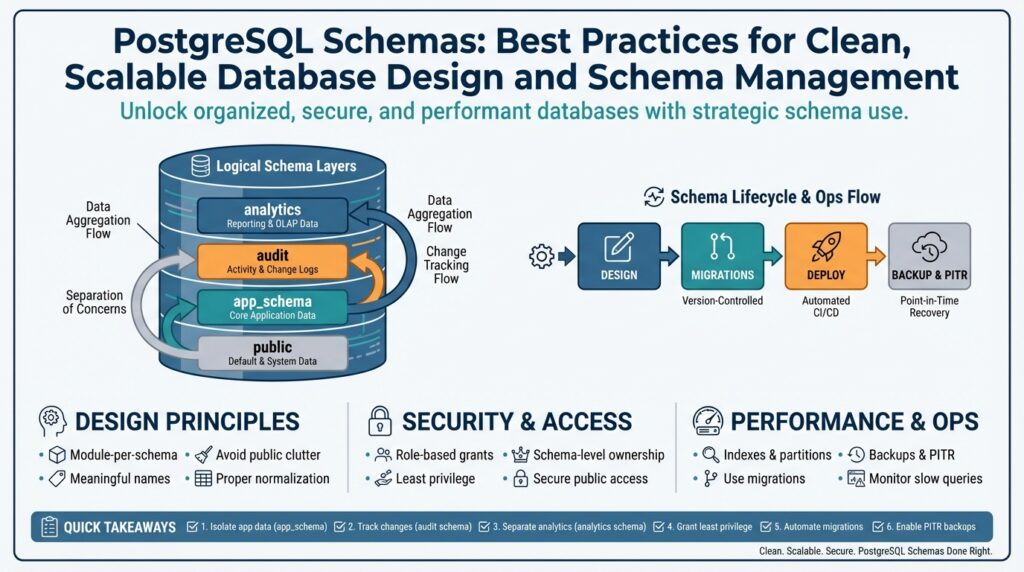

When a database grows beyond a handful of tables, the hardest problem isn’t storage—it’s organization. PostgreSQL schemas give you an explicit namespace for grouping related objects (tables, views, functions) so you can reason about ownership, lifecycle, and access without changing the database itself. Think of a schema as a directory inside the database: it prevents name collisions, clarifies intent, and surfaces boundaries that both developers and automation can rely on. Building on this foundation makes subsequent schema management and migrations far more predictable.

Separation of concerns is the most immediate payoff. You get logical isolation for subsystems or tenants without provisioning new database instances, which reduces operational cost and simplifies networking. How do you model this in practice? For a multi-tenant product we often create tenant_<id> schemas and run schema-qualified queries like SELECT * FROM tenant_42.users; combined with SET search_path per session you can give application connections a seamless, tenant-scoped view of the data. This pattern enables per-tenant extensions, per-schema extensions, and targeted backups while keeping a single connection pool.

Security and least-privilege become easier when you scope permissions to a schema. Grant USAGE and SELECT on a schema to an analytics role while denying CREATE privileges to reduce the blast radius of a compromised account. We consistently assign service roles to specific schemas so CI systems or batch jobs only see the objects they need, and we use default privileges to ensure newly created tables inherit the correct access model. That scoping reduces accidental cross-team access and makes audits and compliance checks more straightforward.

Schema-aware migrations make evolving a complex system manageable. Instead of a monolithic migration that touches every table, you can write migration scripts targeted at schema_x only, run them inside transactions, and roll back safely on failure. Use schema-qualified DDL in your migration tooling (CREATE TABLE analytics.events (...)), and tag migrations by schema so rollouts and reprovisioning are deterministic. This approach supports independent lifecycle for analytical schemas, experimental features, or service-specific tables without locking the entire database for maintenance.

Operational maintenance and developer ergonomics improve immediately when team conventions treat schemas as first-class design artifacts. Developers find it easier to navigate object names, operators avoid accidental table shadowing, and DBAs can dump or restore a schema (pg_dump -n tenant_42) instead of the whole cluster during incident response. While schemas don’t change core query planning, they simplify indexing strategies, maintenance windows, and ownership transfers because you’re working at a logical unit of organization rather than an amorphous set of tables.

There are trade-offs to acknowledge: thousands of tiny schemas can complicate catalog performance and cross-schema joins add explicit qualification overhead, so evaluate schema-per-tenant only when tenant counts and operational constraints warrant it. When applied judiciously, schemas give you modularity, clearer ownership, and safer deployment patterns, which set the stage for the conventions and migration best practices we’ll adopt next.

Schema Naming Conventions

Building on this foundation, a predictable naming strategy is the single biggest leverage you get from PostgreSQL schemas: it makes ownership, automation, and migrations discoverable and scriptable from day one. Start by deciding the few orthogonal axes you care about—team ownership, environment, tenant or service boundary—and bake those into names consistently. How do you name schemas so they scale? We’ll focus on practical, machine-friendly patterns that minimize surprises during deployments and audits while keeping human-readability.

The first rule: favor lowercase, alphanumeric names with underscores (snake_case) and avoid quoted identifiers. PostgreSQL treats unquoted identifiers as lowercase, so using mixed case or punctuation forces double quotes and brittle references across tooling. Keep names short and meaningful: default PostgreSQL identifier length is limited (historically 63 bytes), so long verbose names will be truncated; choose concise tokens like analytics, billing, tenant_42 rather than AnalyticsDataForQuarterlyReporting. Avoid reserved words and characters like hyphens, spaces, and dots that complicate shell scripts and ORM code.

Adopt stable prefixes that encode intent and ownership rather than ad hoc labels. Use svc_ or app_ for service-scoped schemas (for example svc_orders), analytics_ for reporting (analytics_events), and tenant_ for per-tenant isolation (tenant_1234). For environment separation, prefer a deployment-level scope outside the cluster (separate DB per env) or, if you must, an explicit prefix such as dev_/stg_/prod_—but only when your CI/CD tooling and RBAC can enforce environment boundaries reliably. Keep one convention across teams so automation can infer role mappings (for instance map svc_* to a service role and apply GRANT USAGE once).

Multitenancy naming deserves special care because it multiplies schema counts. Use stable, short tenant identifiers that are safe to embed in object names—numeric IDs or compact UUID segments (tenant_42, tenant_b7f3)—and never expose PII in schema names. We prefer tenant_{id} over human names since IDs are immutable and scriptable; if you use a UUID, truncate consistently and document the truncation policy to avoid collisions. Also avoid creating schema names dynamically in application code at runtime unless you have strict lifecycle management; instead, provision schemas via migrations or provisioning jobs so you can track ownership and apply default privileges predictably.

Make your migration and tooling practices schema-aware. Always use schema-qualified DDL in migrations (CREATE TABLE analytics.events (...)) and tag migrations by schema in your migration repository so you can run targeted rollouts and rollbacks. Name migration files or jobs with the schema token (20260109__analytics__create_events.sql) to ease auditing and to support per-schema CI pipelines. Map service roles to schema names in your infra code (for example role svc_orders owns svc_orders) and apply default privileges so newly created objects inherit the intended access model without manual intervention.

Operational governance is where naming conventions pay dividends. Maintain a small registry or centralized README that lists schema prefixes, ownership, and intended lifecycle; use automated checks in CI to validate schema names against a regex to prevent drift. When deciding whether to create a new schema versus adding a table prefix, weigh the lifecycle and permission surface: create a schema when you need distinct ownership, backups, or extensions; prefer table prefixes when objects share the same lifecycle and role set. Consistent names also make catalog queries, pg_dump -n, and incident runbooks straightforward—automation expects patterns, so give it predictable names.

If you invest time in clear, consistent schema names, you reduce cognitive load and make automation reliable. We recommend codifying the conventions in a short doc, enforcing them with CI checks, and using schema-qualified DDL in all tooling so your migration stories remain reproducible. Next, we’ll take these naming choices into migrations and show how schema-scoped rollout strategies keep change windows small and reversible.

Security and Privileges

Building on this foundation, think of schemas as both organization and the primary security boundary you can enforce without changing application code. Treating PostgreSQL schemas as first-class security units lets you apply least-privilege principles at the namespace level, limit blast radius, and make audits meaningful because ownership and permissions reflect real team or service boundaries. Use schema-aware role mappings in your infrastructure code so access is predictable and auditable; this reduces the chance that a developer or CI job inherits broader rights than intended. PostgreSQL schemas give you a practical surface for applying role-based access control and automated governance in a single cluster.

Start with explicit role definitions and avoid granting broad rights to PUBLIC. Create focused roles for services (for example svc_orders_ro for read-only analytics) and human groups (for example eng_billing). Then grant schema-level privileges like USAGE to allow name lookup and SELECT on specific tables while denying CREATE to prevent unauthorized object creation. For example, run:

CREATE ROLE analytics_ro NOLOGIN;

GRANT USAGE ON SCHEMA analytics TO analytics_ro;

GRANT SELECT ON ALL TABLES IN SCHEMA analytics TO analytics_ro;

REVOKE CREATE ON SCHEMA analytics FROM PUBLIC;

These statements give analytics read access without widening the attack surface, and they make the access model explicit in your migration scripts.

Default privileges are the next lever to lock down future drift: they ensure objects created later inherit the intended ACLs so you don’t have to patch permissions reactively. Set default privileges per role and per schema so objects created by a service account immediately follow your policy, for example:

ALTER DEFAULT PRIVILEGES FOR ROLE svc_orders_owner IN SCHEMA svc_orders

GRANT SELECT ON TABLES TO svc_orders_ro;

ALTER DEFAULT PRIVILEGES FOR ROLE svc_orders_owner IN SCHEMA svc_orders

REVOKE CREATE ON SCHEMA svc_orders FROM PUBLIC;

This keeps migrations and provisioning idempotent: new tables and views won’t accidentally open access.

Multi-tenant deployments change the threat model, so map tenant schemas and service roles deliberately and rotate credentials frequently. When should you use schema-based isolation versus row-level security? Use per-tenant schemas when you need independent ownership, per-schema extensions, or separate backup/restore; prefer row-level security (RLS) when you need a single schema for operational simplicity and connection-pool reuse. If you use connection pooling, avoid embedding tenant identifiers in long-lived connection roles without careful session initialization (SET search_path or SET ROLE) and prefer short-lived tokens or pooler features that set per-request session state safely.

Operational hygiene matters as much as ACLs. Revoke default privileges on public schemas early (REVOKE CREATE ON SCHEMA public FROM PUBLIC) and script ownership transfers during migrations to avoid orphaned objects. Automate permission checks in CI: validate that schema names match your prefix conventions, verify default privileges are set, and flag any migration that grants CREATE or SUPERUSER-like rights. Regularly audit role memberships, export ACLs for compliance checks, and test restoring a schema with pg_dump -n to confirm your backup and restore permissions behave as expected.

Security controls are only useful if they’re reproducible in your pipelines, so codify role-to-schema mappings in infrastructure code and embed privilege-setting SQL in migrations. We’ll next show how to write schema-scoped migrations and rollout strategies that preserve these ACL invariants during deployment, letting you evolve schemas without opening temporary access holes.

Multi-tenant Schema Strategies

Building on this foundation, choosing the right multitenancy strategy is one of the highest-impact architectural decisions you’ll make for a SaaS database. In a multi-tenant system you can take several paths—schema-per-tenant, shared schema with tenant_id columns, or a hybrid—and each option changes how you provision, secure, and migrate data. How do you decide between schema-per-tenant and row-level security approaches for your product? We’ll compare trade-offs in operational cost, isolation, backup granularity, and connection-pool behavior so you can pick the pattern that fits your SLAs and team constraints.

When isolation and independent lifecycle matter, schema-per-tenant shines: you get per-tenant ownership, targeted backups with pg_dump -n, and the ability to install extensions or custom objects for specific tenants without affecting others. This pattern favors customers that require tenant-level encryption, separate restore windows, or regulatory isolation because you can restore a single schema or revoke a service role for one tenant. However, schema-per-tenant has measurable catalog and planning costs at scale—thousands of schemas increase system catalog size and complicate cross-tenant analytics—so reserve it for tenants that justify the operational overhead rather than applying it universally.

If you opt for schema-per-tenant, make provisioning and naming deterministic and script-driven so schemas are reproducible and auditable. Provision schemas from your orchestration or migration pipeline rather than creating them ad hoc at request time, and use short stable identifiers (for example tenant_42 or tenant_b7f3) to avoid PII leakage and naming drift. Apply default privileges during provisioning so newly created tables inherit the correct ACLs, and set the session search_path (for example SET search_path = tenant_42, public) as the first step on connection checkout to present a tenant-scoped view to application code while retaining a single logical connection pool.

Connection pooling is where design meets reality: many high-performance poolers operate in transaction mode and do not preserve session state, which breaks patterns that rely on per-connection search_path. If you use a transaction-pooling proxy like PgBouncer in transaction mode, avoid persisting tenant identity solely via SET search_path on long-lived connections; instead either use session pooling, reapply search_path immediately after checkout for every transaction, or move tenant routing logic to the application layer (query schema-qualified names explicitly) to keep connections safe and predictable. Prepared statements and cached query plans can also leak across tenants if you change search_path mid-session, so test for plan stability in your CI before rolling out multi-tenant pooling strategies.

Cross-tenant queries and analytics require special handling to avoid performance traps. For real-time cross-tenant joins, prefer a shared analytics schema or ETL pipeline that consolidates necessary columns into a reporting store rather than doing frequent cross-schema joins on OLTP tables—the planner cost and locking behavior can degrade under many concurrent schema-qualified joins. For occasional admin queries, tools like dblink or a read-only reporting replica can reduce load on production; for frequent analytics, push data to a warehouse and keep tenant schemas focused on operational workloads.

Migrations and lifecycle for tenant schemas should be incremental and schema-aware so you can roll out changes safely across many tenants. Tag migration files with the schema token and run schema-scoped migrations in controlled batches; for backward-compatible changes prefer additive DDL and separate schema-wide refactors into a staged rollout. Automate validations: run a dry-run migration against a snapshot, verify default privileges, and test restore of a single schema to ensure your backup strategy meets recovery objectives. Taking these precautions keeps schema-per-tenant maintainable and lets you scale without surprising downtime.

Taking this concept further, design your infrastructure so tenant isolation is explicit in both naming and access control; when you combine thoughtful provisioning, cautious pooling, and schema-aware migrations you get predictable operational behavior and a clearer security boundary. Next we’ll apply these strategies to migration tooling and rollout patterns so we can evolve tenant schemas incrementally while preserving ACL invariants and minimizing change windows.

Schema Migration Practices

Schema migration is where organization meets operational risk: you can architect perfect PostgreSQL schemas, but without controlled migrations those boundaries will erode. In the first 100 words we should be explicit: treat schema migrations as transactional, idempotent operations that respect schema-qualified boundaries, and automate them so you never apply ad hoc DDL in production. If you follow a few core principles we can keep change windows small, roll back safely, and preserve ACLs and default privileges across deploys. How do you roll back a change that touched hundreds of tenant schemas without downtime? We’ll show patterns that make that practical.

Make every migration atomic and idempotent whenever possible. Start a migration by acquiring an application-level or advisory lock so only one process touches a schema at a time, then run your DDL inside a transaction where Postgres supports it. Design schema migrations to be reversible: prefer additive changes (add column, create new table, add index) and avoid destructive refactors in a single step. Note that some operations—CREATE INDEX CONCURRENTLY and certain extension installs—cannot run inside transactions; detect and handle these as out-of-band steps in your pipeline with explicit sequencing and monitoring.

When you change table shape, separate schema evolution into small, observable phases. For example, add a nullable column, backfill rows in controlled batches, switch application writes to populate the new column, validate dual reads, then issue the NOT NULL enforcement and drop the old column. Practical SQL pattern:

BEGIN;

SELECT pg_advisory_xact_lock(12345); -- per-schema lock

ALTER TABLE analytics.events ADD COLUMN new_user_id bigint;

COMMIT;

-- Backfill in batches (outside a single transaction)

UPDATE analytics.events SET new_user_id = user_id WHERE new_user_id IS NULL LIMIT 10000;

This pattern avoids long table rewrites and keeps the database responsive during migration.

Make your tooling schema-aware so deployments can target one namespace at a time. Tag migration files with the schema token and enforce schema-qualified DDL (SET search_path = analytics; CREATE TABLE analytics.events (...)) to prevent accidental cross-schema changes. Run migrations in controlled batches for tenant or service schemas and use CI to validate idempotency and default-privilege invariants before touching production. We recommend keeping a per-schema migration table that records version, checksum, and applied_at to make auditing and safe rollbacks deterministic.

Plan rollout strategies around compatibility and pooling constraints. If you use connection poolers that operate in transaction mode, avoid relying on session-local state like search_path persisting across transactions; prefer explicit schema-qualified queries or reapply SET search_path immediately after checkout. For multi-tenant rollouts, stagger migrations in waves (canary tenants, small production slice, then full rollout) and couple DDL with feature flags so application behavior can switch cleanly between old and new schema shapes. When an index is required without locking writes, use CREATE INDEX CONCURRENTLY as a separate step and monitor progress closely.

Finally, test migrations against real snapshots and automate restore verification for each schema. Run a dry-run migration against a recent pg_dump or a restored clone, verify grants and default privileges, and run your smoke tests including permission checks and sample cross-schema queries. Instrument migrations with metrics and alerts so failed steps trigger automated rollback or pause the pipeline for human review. Taking these practices together—transactional intent, phased rollout, schema-aware tooling, and rigorous test/restore validation—lets us evolve PostgreSQL schemas confidently without creating surprise outages or security drift.

Building on the naming, privilege, and multi-tenant guidance above, the next practical step is to codify these schema-scoped migration patterns into your CI/CD pipelines so migrations become repeatable, observable, and reversible across environments.

Indexing and Partitioning

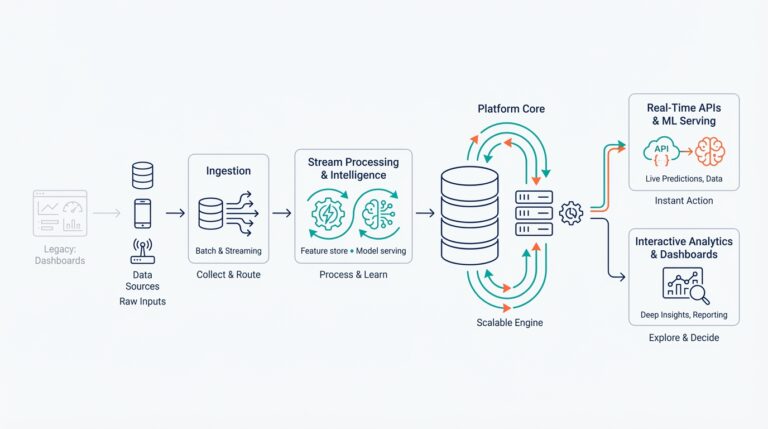

Building on this foundation, effective PostgreSQL index and partition strategies are the difference between a responsive production cluster and one that grinds under growth. If your schemas already separate ownership and lifecycle, the next step is to align indexing and partitioning with those boundaries so queries hit targeted objects rather than the whole catalog. How do you choose the right index type or partitioning key for a service or tenant schema? We’ll show practical patterns you can apply today—including concrete SQL idioms you can slot into your migrations and provisioning jobs.

Start with the query patterns you see in each schema and create indexes that match predicates, joins, and ordering. For OLTP schemas used by services, that usually means B-tree indexes on foreign keys and highly selective columns, plus occasional expression or partial indexes for common WHERE filters (for example CREATE INDEX ON svc_orders (customer_id) or CREATE INDEX ON svc_orders ((lower(email))) WHERE deleted = false). Build these indexes in the owning schema and name them predictably so automation can manage them (svc_orders_customer_id_idx), and prefer CREATE INDEX CONCURRENTLY for production builds that must avoid locking writes—remember CREATE INDEX CONCURRENTLY cannot run inside a transaction, so treat it as an explicit out-of-band step in your pipeline.

Partition tables when a single table’s size or lifecycle makes pruning and maintenance necessary. Range partitioning by time is the canonical example for event logs and audit tables: put recent months in active partitions and older months on cheaper storage. You can also partition by tenant identifier when tenant-per-schema is impractical but per-tenant pruning or data lifecycle is required. In SQL terms you create a partitioned root table in the appropriate schema (CREATE TABLE analytics.events ( ... ) PARTITION BY RANGE (created_at)), then create per-range child partitions (CREATE TABLE analytics.events_2025_01 PARTITION OF analytics.events FOR VALUES FROM (...) TO (...)). Keep partition naming consistent with your schema conventions to make programmatic maintenance straightforward.

Understand how indexes and partitions interact: PostgreSQL treats indexes as local to each partition, so you typically create the necessary index once on the parent and let the system propagate it to new partitions, or create indexes on each attached partition. Global indexes across partitions aren’t natively available, which affects queries that need cross-partition uniqueness checks—plan for that by adding application-level constraints or by designing the partition key so uniqueness is local. When you attach a new partition, create its indexes (again, CONCURRENTLY in production) and validate constraint checks; this minimizes locks and keeps query latency predictable during partition lifecycle events.

Choose index types and selective predicates carefully based on cardinality and update patterns. High-cardinality equality filters and join keys are B-tree territory; range scans and ORDER BY benefit from composite indexes that match the sort order. For low-cardinality flags or soft-delete markers, a partial index like CREATE INDEX ON analytics.events (user_id) WHERE deleted = false can reduce IO and improve planner cost estimates. Monitor pg_stat_all_indexes and pg_stat_user_indexes and use EXPLAIN (ANALYZE, BUFFERS) to validate that an index is used; if you see frequent index scans with low selectivity, reconsider the index or add a covering index to avoid heap fetches.

Operationally, bake index and partition work into your schema-scoped migration pipeline so changes are incremental and reversible. For a partition rollout: create the new partition, backfill data in controlled batches, ATTACH the partition, then create indexes CONCURRENTLY and run constraint validation. For large index builds on busy tables, run them during a maintenance window or on a read-replica and promote or swap once ready. We also recommend scripting index naming, per-schema index ownership, and default-privilege application so newly provisioned partitions immediately inherit your access and monitoring policies.

Taken together, indexing and partitioning let you scale PostgreSQL schemas without surrendering predictability: indexes tune access paths, partitioning confines maintenance work, and schema-aware naming keeps automation reliable. As you implement these patterns, align them with your migration practices and multi-tenant decisions from earlier sections so rollouts are staged, auditable, and reversible. In the next section we’ll apply these operational patterns to schema-scoped migration tooling and show step-by-step scripts you can run in CI to keep indexes and partitions healthy as your cluster grows.