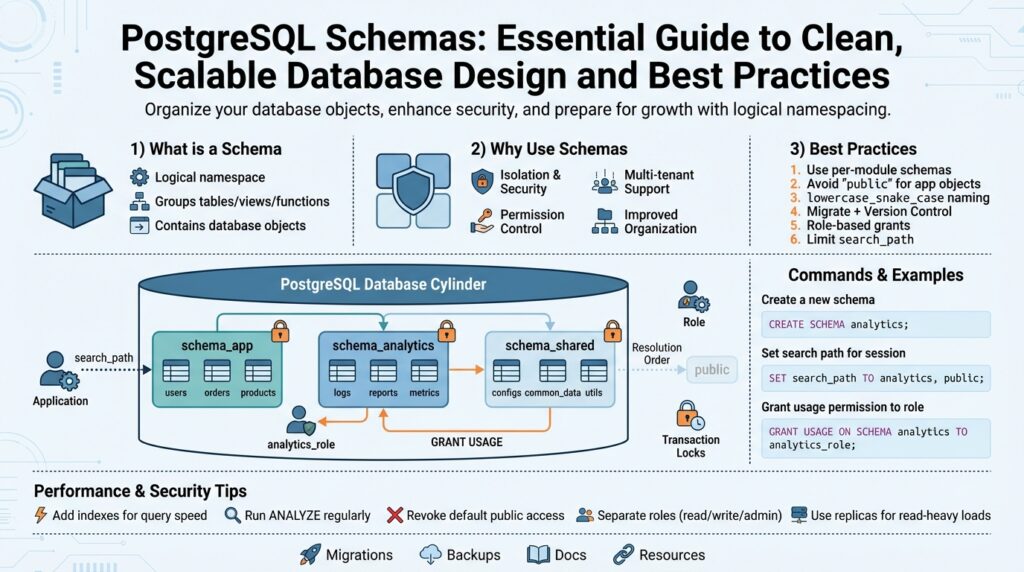

What is a PostgreSQL schema

If your database feels like a junk drawer where tables, functions, and types collide, a PostgreSQL schema gives you a way to impose order without creating new databases. A PostgreSQL schema is a logical namespace inside a single database that groups related objects—tables, views, sequences, functions, types—so you can reason about ownership, access, and naming independently from other groups. This lets you avoid global name clashes, grant permissions at a finer granularity, and map application boundaries to database organization rather than spinning up additional database instances.

At its core, a schema is a container for database objects. Each database has a default “public” schema and a search_path that determines how unqualified object names are resolved; you can create additional schemas to separate modules, teams, or tenants. The schema name becomes part of the fully qualified identifier (schema.table), and you can control visibility by adjusting the search_path or schema-level privileges. When you say “PostgreSQL schema,” think of it as a folder for database objects that preserves a single connection and transaction scope while giving you logical separation.

Why would you use separate schemas instead of separate databases or prefixes? Separate schemas are useful when you want strong logical isolation but still need shared resources like cross-schema foreign keys, shared extensions, or centralized backup policies. For multi-tenant systems you can place each tenant in its own schema to simplify routing and reduce the operational cost of many database instances; for modular applications you can allocate a schema per bounded context so teams can own migrations and privileges independently. When should you create separate schemas versus separate databases? Choose schemas when you need transactional joins and shared server configuration; choose separate databases when tenant resource isolation or independent backups per tenant are strict requirements.

Practically, using schemas is straightforward and controlled by a few SQL primitives. Create a schema and own it with:

CREATE SCHEMA billing AUTHORIZATION billing_role;

SET search_path = billing, public;

CREATE TABLE billing.invoices (id serial PRIMARY KEY, amount numeric);

GRANT USAGE ON SCHEMA billing TO app_role;

GRANT SELECT, INSERT ON ALL TABLES IN SCHEMA billing TO app_role;

This pattern shows explicit schema qualification (billing.invoices) and a recommended practice: grant USAGE on the schema separately from table privileges so you avoid accidental access through the search_path.

There are operational trade-offs you must manage when adopting schemas. Schemas do not provide CPU or disk isolation—queries in one schema can still affect overall database performance—so monitoring and resource management remain central. Migrations become more complex when you have many schemas, because tools like Flyway or Liquibase must be configured to run migrations per schema or to include schema name prefixes; backups with pg_dump need the -n/–schema option to target a subset. Overuse of schemas can make security auditing and query ownership harder, so balance granularity with maintainability.

To get the most value from schemas, adopt consistent naming conventions, align schema ownership with roles, and decide a clear migration strategy before you add many schemas. Use schemas for modular separation, tenant grouping, or staging environments within the same database, and reserve separate databases when you need strong operational isolation. Building on this foundation, we’ll next examine schema design patterns and migration strategies that keep your PostgreSQL schemas clean, auditable, and aligned with team responsibilities.

When to use schemas

Deciding whether to introduce PostgreSQL schemas into your database design starts with a concrete operational question: are you solving a naming and ownership problem, or are you trying to create a hard isolation boundary? If your pain is accidental name collisions, muddled ownership, or coarse-grained privileges, schemas give you a lightweight, within-database solution that preserves transactional joins and shared configuration. Front-load this distinction when you evaluate architecture choices so you don’t conflate logical separation with resource isolation.

Start by evaluating the guarantees you need. Use schemas when you require logical isolation—separate naming, role-aligned ownership, or scoped privileges—while still needing intra-database transactions, cross-schema foreign keys, or centralized backup policies. If you need per-tenant CPU, memory, or disk limits, or if independent restore windows per tenant are mandatory, a separate database (or instance) is the safer choice. Weigh these trade-offs against operational complexity: schemas simplify routing and reduce instance count, but they do not provide true resource sandboxing.

Multi-tenant systems are the most common trigger for picking schemas, but the choice isn’t binary. How do you decide between tenant-per-schema and a single shared schema with tenant_id? Choose tenant-per-schema when tenants require distinct ownership, custom extensions, or substantially different schemas over time; this pattern makes it easier to grant tenant-specific roles and to run tenant-scoped migrations. Prefer a shared schema with a tenant_id column when you expect thousands of small tenants, when schema uniformity is essential, or when connection-pool scaling is a top priority.

Schemas also shine for modular application design and team autonomy. When you map bounded contexts—billing, analytics, identity—into separate schemas, teams can own migrations, roles, and naming without tripping over each other. Practically, we create a schema per service boundary, assign an authorization role to own it, and configure our migration tooling to operate per schema so CI pipelines can run independent schema migrations. This mirrors domain-driven design in the database and reduces cross-team deployment coordination.

Operational realities drive the decision more than theory. Plan migrations, backups, and connection pooling with schemas in mind: migration tools like Flyway or Liquibase must be configured to target schemas or include schema-qualified object names; pg_dump and pg_restore require the -n/–schema flags for selective backups; and connection pools can suffer from many distinct search_path settings if you use per-tenant roles. Monitor catalog and object counts—overusing schemas can increase complexity for auditing and make global refactors costly, so adopt conventions for naming, privileges, and lifecycle management up front.

Consider a practical mapping from a mid-size e-commerce platform: put billing and payments in a billing schema owned by billing_role, analytics pipelines in an analytics schema with restricted access, and customer-specific data either in tenant schemas for enterprise clients or in a shared orders table keyed by tenant_id for thousands of smaller stores. This hybrid approach gives you the flexibility to escalate certain customers to isolated schemas without rearchitecting the entire data model, while keeping day-to-day operations predictable.

Before you add many schemas, run a short checklist: inventory access patterns, decide whether cross-schema transactions are required, define migration strategy per schema, and align schema ownership with roles. Building on this foundation, next we’ll dig into concrete schema design patterns and migration strategies that make these choices operationally sustainable and auditable. Would you like an example Flyway configuration illustrating per-schema migrations?

Create and manage schemas

A common source of runtime confusion is not how to create a schema but how to own and operate it safely over time. How do you create, configure, migrate, and retire logical namespaces without introducing accidental access or operational debt? Start by treating a PostgreSQL schema as a first-class resource: give it a clear name that reflects its bounded context, assign a single owning role, and document its intended lifecycle. Establishing these rules up front prevents ad-hoc schemas from proliferating and makes later audits far easier.

When you create a namespace, prefer explicit ownership and minimal default privileges so you avoid broad accidental access. Create the schema under a role that represents its owning team or service, then grant only the required rights to application roles; keep schema-level privileges separate from table privileges to avoid leaks via the search_path. For example, create and assign ownership, then grant usage:

CREATE SCHEMA analytics AUTHORIZATION analytics_role;

GRANT USAGE ON SCHEMA analytics TO app_role;

GRANT SELECT ON ALL TABLES IN SCHEMA analytics TO app_role;

This pattern keeps ownership clear and lets you rotate or audit roles without touching object-level grants.

Explicit object qualification should be your default for production code. Relying on search_path can be convenient during development but introduces subtle bugs when connection pools, middleware, or CI runners set different search paths. Qualify critical references as schema.table in queries and migrations so you don’t accidentally hit similarly named tables in other namespaces. When you must use search_path for multi-schema resolution, set it per-connection and document the exact ordering; avoid per-request dynamic search_path changes in pooled environments because many pools reuse connections.

Migrations require a disciplined approach when you have many namespaces. Run schema-scoped migration scripts and tag them with the schema name in your migration tool (schema migration scripts), or run a migration pipeline per owning role so deployments map to team ownership. Write idempotent DDL where possible and use advisory locks or your migration tool’s built-in locking to prevent concurrent schema migrations from colliding. For tenant-per-schema patterns, automate schema provisioning and baseline the migration state for new schemas so you can spin up or tear down tenants reproducibly.

Backups and restores must be schema-aware. Use pg_dump/pg_restore with the -n/–schema option for targeted backups and test restores into sandbox databases regularly to validate dependencies across schemas. Remember that cross-schema foreign keys and functions create restore-order constraints; a schema-level dump may still require dependent objects from another schema, so include those dependencies or perform a coordinated restore. Automate selective dumps for high-value schemas and ensure your runbooks include step-by-step restore verification.

Managing schema lifecycle means you’ll encounter dependencies and catalog queries regularly; use the system catalogs to inspect and validate before making changes. Query pg_namespace, pg_class, and information_schema to enumerate objects that will be affected before you ALTER or DROP a namespace. When removing schemas prefer a staged approach: revoke external access, move or archive data, run dependency reports, then drop with confirmation; avoid DROP SCHEMA … CASCADE as a first step because it removes objects you might need to recover.

Building on this foundation, codify naming conventions, ownership mapping, and migration practices in a repository readme so teams can follow a repeatable pattern. Monitor schema growth, object counts, and query patterns per schema to detect hotspots and make informed choices about whether to split or consolidate namespaces. In the next section we’ll translate these operational patterns into concrete schema design patterns and CI/CD recipes that keep your PostgreSQL schema strategy auditable and scalable.

Manage schema ownership and permissions

Building on this foundation, treat ownership and permissions as part of your schema’s life cycle rather than an afterthought. Ownership determines who can modify DDL, while permissions control who can see or modify data; getting these two aligned reduces accidental changes and privilege creep. Start by mapping each PostgreSQL schema to a team or service role that will own it, and document that mapping in your infra repository so ownership is discoverable. When you tie schema ownership to a dedicated role, you make audits, role rotation, and emergency access far more predictable.

When assigning ownership, prefer role composition over individual users so you can rotate people without touching grants. Create a role such as billing_owner that owns the namespace and a separate billing_app role for runtime access, then use ALTER SCHEMA ... OWNER TO billing_owner for clear accountability. For runtime permissions, grant the minimal set of actions the application needs—USAGE on the schema plus the specific table-level privileges—rather than granting broad superuser-like rights. This separation between owning role and application role prevents accidental DDL changes during deployments and supports the principle of least privilege.

How do you safely change who owns a schema or rotate elevated access in production? Use staged steps: revoke or lock down external access, transfer ownership with ALTER SCHEMA ... OWNER TO new_role, update any ALTER DEFAULT PRIVILEGES rules, run a deploy that verifies the new owner can perform intended migrations, and finally remove the old owner from sensitive roles. Combine this with audit hooks: capture pg_event_trigger or simple DDL logging so you can trace who changed ownership or altered privileges. These practices reduce blast radius when you must rotate secrets, onboard contractors, or merge teams.

Permissions management must also account for future objects. Use ALTER DEFAULT PRIVILEGES FOR ROLE deploy_role IN SCHEMA payments GRANT SELECT ON TABLES TO analytics_role; so tables created later inherit intended grants without manual steps. Default privileges let you codify the contract between teams: infrastructure roles create objects, and consumer roles receive only the access they need. When your CI runs migrations, ensure the pipeline operates under the owning role or uses an explicit SET ROLE to avoid leaving objects owned by ephemeral CI accounts, which complicates later privilege management.

Practical enforcement and verification belong in automation and quick diagnostics. Add pre-deploy checks that query pg_namespace, pg_roles, and pg_default_acl to validate ownership and default grants before migrations run, and include a small SQL script in your pipeline that fails fast on mismatches. For day-to-day troubleshooting, a simple query such as SELECT nspname, pg_get_userbyid(nspowner) FROM pg_namespace WHERE nspname = 'analytics'; gives immediate ownership insight. We should also limit reliance on search_path for security decisions: explicit schema qualification in SQL reduces accidental access when pool settings vary and makes permission boundaries explicit.

Finally, think about long-term maintainability: codify ownership and permissions in your repo, run periodic audits that compare declared policy to actual grants, and bake revoke-and-regrant playbooks into runbooks for safe recovery. Treat high-value schemas—tenant namespaces, payment, analytics—as guarded resources with separate backup and restore procedures that respect their permissions model. By aligning PostgreSQL schema ownership with team roles, automating default privileges, and validating state in CI, we keep your namespaces secure, auditable, and operationally manageable as your system scales.

Naming and organization conventions

If your database looks like a grab-bag of ad-hoc names, naming and organization will buy you weeks of future debugging time. Building on this foundation, we treat PostgreSQL schemas as discoverable, predictable namespaces rather than free-form labels; that mindset shifts decisions from “what worked last time” to “what will scale.” Start by deciding a small set of clear patterns you and your team will follow and commit those rules to your infra repository so everyone and every migration tool can depend on them.

The first principle is consistency: prefer lowercase, underscore-separated identifiers and avoid special characters or quoted mixed-case names. Using snake_case for schema and object names eliminates surprises from PostgreSQL’s case-folding rules and keeps tooling simple: billing_reports rather than “BillingReports”. Reserve short prefixes that convey ownership or responsibility—billing_, analytics_, or tenant_—and map each prefix to a role (billing_role owns billing_*). This convention makes it obvious who should run migrations, who owns backups, and which role to grant USAGE to without inspecting the catalog.

How do you name schemas for tenants so provisioning, backups, and restores are predictable? For tenant-per-schema models choose stable, human-readable identifiers when tenants are few and high-value (tenant_acme, tenant_globex). When you expect thousands of tenants, use a compact, deterministic scheme such as tenant_12345 or a short hashed suffix to keep names compliant and searchable (tenant_1a2b). Avoid embedding ephemeral metadata like environment or timestamp into the primary schema name; treat those as orthogonal lifecycle tags documented elsewhere.

Organize names to reflect lifecycle and environment, but prefer orthogonal mechanisms over ad-hoc suffixes. Many teams are tempted to append _dev/_staging/_prod to schema names; instead, we recommend separating environments at the database or cluster level when possible and using a controlled naming registry for any environment-scoped schemas you must create. If you must tag schemas for temporary use—migrations in progress, archive imports—use a short, documented suffix such as _tmp or _archive and enforce automatic cleanup policies so those names don’t leak into production workflows.

Name objects inside schemas so relationships and ownership are immediately clear. We prefer schema-qualified references in production code (billing.invoices) and explicit, descriptive constraint names like invoices_pkey and invoices_customerid_fkey to make log messages and pg_catalog inspection meaningful. Example patterns: table names as nouns (invoices), sequences as table_column_seq (invoices_id_seq), and functions prefixed with the owning domain (billing.calculate_tax()). Use CREATE SCHEMA and explicitly set ownership in your migration scripts so names and roles are coupled rather than inferred at runtime.

Tooling and migration compatibility should drive small but important naming choices. Keep schema names stable—renaming a schema is higher friction than renaming a table—so prefer indirection (views or synonyms) when you need to present a new surface without a costly rename. Make your migration tool (Flyway, Liquibase) expect schema-qualified SQL and standardize schema naming in CI variables; add a preflight check that queries pg_namespace to fail fast if a schema name violates conventions. Store a simple JSON or YAML registry of schemas and owners in the infra repo so automation can provision, test-restore, and audit with the same authoritative mapping the team uses.

Taking this further, codify these conventions into linters, pre-commit hooks, and CI checks so naming becomes part of the deployment pipeline rather than tribal knowledge. Consistent names speed incident response, simplify audits, and make it safer to run schema-scoped migrations across teams. Next we’ll apply these conventions to concrete schema design patterns and CI/CD recipes so your namespaces remain manageable as the system grows.

Schema migrations and versioning strategies

Building on this foundation, the act of evolving your database schema becomes an operational practice, not an occasional chore. Schema migrations and disciplined versioning are the mechanisms that let teams change PostgreSQL schemas safely, reproducibly, and audibly. How do you keep dozens of namespaces, tenant schemas, and service-owned schemas in sync without creating downtime or surprise breaking changes? We’ll show concrete patterns you can adopt in migration tooling and CI so DDL changes behave like well-tested software releases.

Start by treating migration state as the single source of truth. Use a migration table (the history table your migration tool maintains) to record applied changes, and decide whether that table lives per schema or globally; each choice has trade-offs. A per-schema migration history isolates ownership—each team or tenant can roll forward independently—while a global history simplifies cross-schema refactors and avoids duplicated metadata. Choose a consistent versioning scheme (monotonic integers, timestamped versions, or semantic-style prefixes) and encode it in filenames so you can audit what ran and why.

Adopt strict naming and idempotency patterns for migration files so your pipelines can run them safely. Name files with a predictable header such as V20260108__create_billing_schema.sql or V1__add_invoices_amount.sql so diffs are obvious in PRs and rollbacks are straightforward to reason about. Keep DDL idempotent where possible—use CREATE SCHEMA IF NOT EXISTS, CREATE TABLE IF NOT EXISTS, and guard ALTER statements with catalog checks to avoid failures when a migration accidentally runs twice. For example:

-- V20260108__create_billing_schema.sql

CREATE SCHEMA IF NOT EXISTS billing AUTHORIZATION billing_owner;

SET ROLE billing_owner;

CREATE TABLE IF NOT EXISTS billing.invoices (

id BIGSERIAL PRIMARY KEY,

amount NUMERIC NOT NULL

);

Concurrency and transactional boundaries matter in practice. Rely on your migration tool’s locking semantics or implement an advisory-lock wrapper so only one process mutates a schema at a time; concurrent DDL runs are the fastest route to corrupted state. Prefer transactional DDL because PostgreSQL rolls back failed migration units automatically, but remember some PostgreSQL commands require special handling—CREATE INDEX CONCURRENTLY cannot run inside a transaction, for example—so separate long-running or non-transactional steps into their own migration files and flag them in CI to run with appropriate safety checks.

Tenant-per-schema deployments need an automated provisioning and baseline pattern. When creating a new tenant schema, run a small bootstrap that creates the schema, sets ownership, and marks the baseline version in the migration history (or use your migration tool’s baseline command). Automate this in your infra repo so provisioning becomes a CI task: create schema -> apply core migrations -> run tenant-specific migrations. Run migrations under the schema-owning role (SET ROLE or dedicated credentials) so objects are owned consistently and default privileges behave as expected.

Testing, rollback, and observability are non-negotiable. Validate migrations in ephemeral environments that mirror production, use feature flags to decouple schema changes from application rollouts, and keep a tested rollback path—either reverse migrations or well-documented restore playbooks with targeted pg_dump/pg_restore steps. Monitor catalog growth and migration history queries in CI preflight checks; fail fast if a migration would violate ownership, depend on missing extensions, or require cross-schema objects that aren’t present.

Taking these approaches together makes schema evolution predictable and auditable. We minimize blast radius by clarifying ownership, we reduce surprises by encoding versioning and naming conventions, and we keep operational complexity manageable with automation for provisioning and baseline steps. In the next section we’ll translate these practices into concrete CI/CD recipes and example pipeline snippets that run per-schema migrations safely in parallel while preserving atomicity and observability.