Failure modes overview

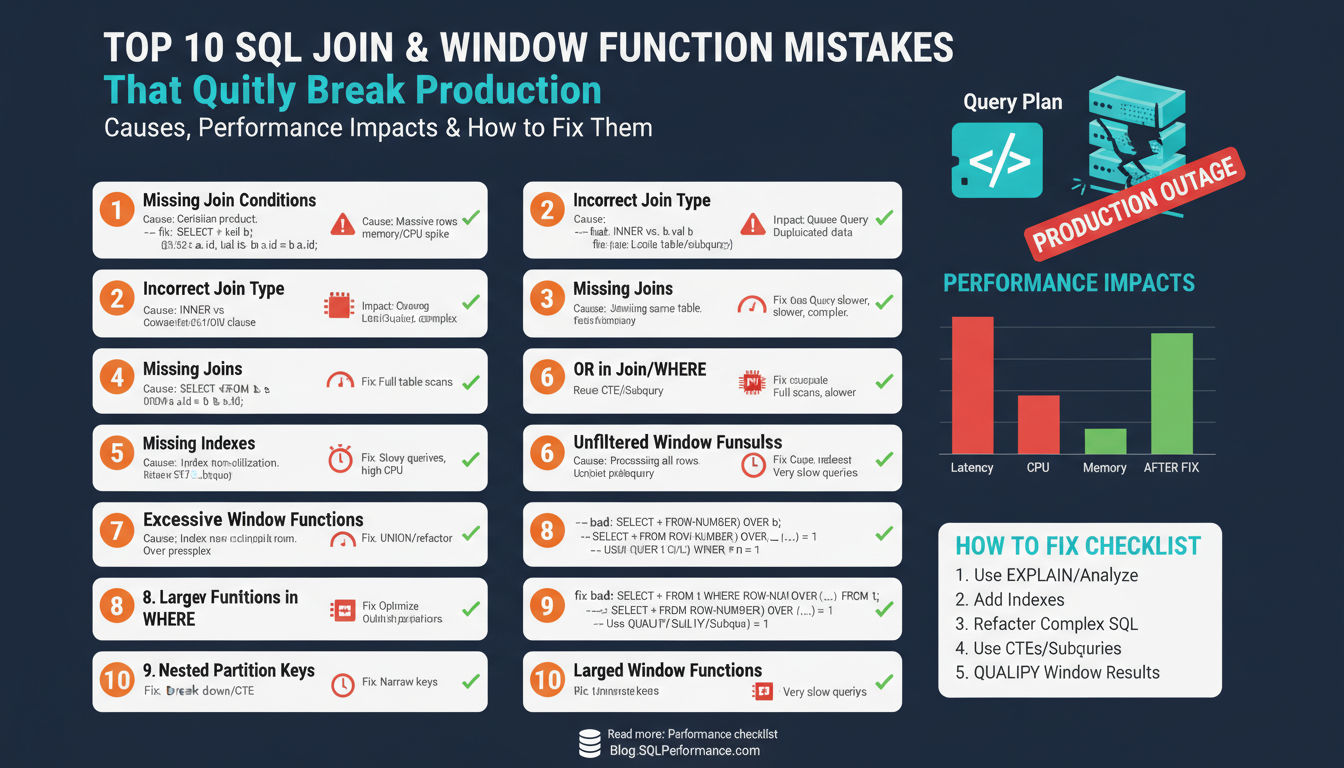

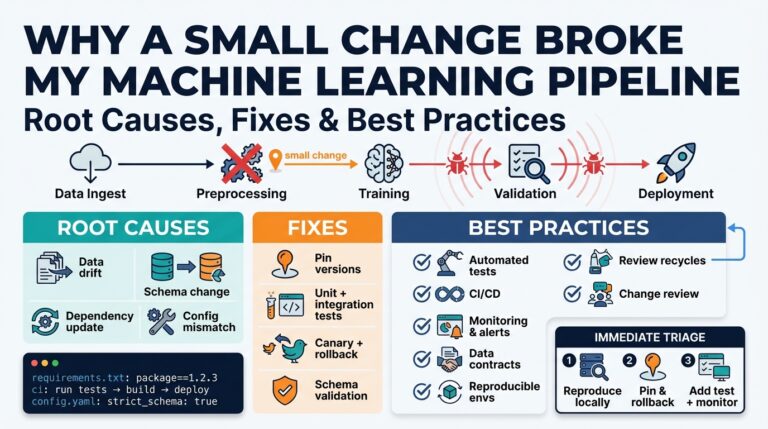

Building on this foundation, the most dangerous failures we see combine subtle correctness bugs with severe query performance regressions, and they usually involve SQL JOINs, window functions, or both. These failures are quiet because they often return plausible-looking results while silently inflating costs: duplicated rows from a misplaced JOIN, mispartitioned aggregates from an unbounded window frame, or a plan that spills to disk under production data volumes. How do you detect the difference between a correctness bug and a performance problem before it hits production?

At a high level, failures fall into three buckets: semantic correctness, resource exhaustion, and execution-plan pathologies. Semantic correctness errors change the meaning of results — for example, using an INNER JOIN where a LEFT JOIN is required will drop rows without obvious errors. Resource exhaustion manifests as memory spills, high temp-storage usage, or transaction log growth that degrade throughput. Execution-plan pathologies are cases where the optimizer chooses a bad join order, introduces nested loops over large datasets, or performs a massive sort for a window function, increasing latency unpredictably.

A few concrete examples make this real. A missing join predicate produces a Cartesian product: a customer table (100k rows) joined without an ON clause to an orders table (1M rows) yields 100 billion rows at the plan level and kills the cluster; that’s a correctness + performance double-whammy. A window function without a proper PARTITION BY (or with ORDER BY that forces a global sort) will materialize huge sort operations: computing ROW_NUMBER() across an entire fact table forces a cluster-wide shuffle in distributed engines and a disk sort in single-node databases. These patterns illustrate why accidental row explosion is the single most common failure vector with SQL JOIN mistakes and window functions.

Operationally, failures show predictable telemetry fingerprints: sudden spikes in disk IO, temp space allocation, increased CPU from sorts, and longer tail latencies. Monitoring these signals (query duration percentiles, spill-to-disk counters, tempdb usage) lets you detect regressions early. Remediation often begins with pushing selective predicates earlier (predicate pushdown), rewriting joins to reduce intermediate row counts, and ensuring statistics and indexes support selective access — practical steps that improve query performance while preserving correctness.

There are subtler correctness traps that won’t show as resource alarms but will silently corrupt results. Window-frame semantics differ: ROWS BETWEEN UNBOUNDED PRECEDING AND CURRENT ROW behaves differently than RANGE BETWEEN; using RANK() vs ROW_NUMBER() changes how ties are handled and can unexpectedly duplicate or omit rows in downstream deduplication logic. NULL-handling on join keys is another frequent cause: implicit NULL mismatches or collation differences can remove matches entirely. Defend against these by writing explicit ON clauses, coalescing join keys when appropriate, and specifying window frames and ORDER BY keys intentionally.

Detecting and preventing these failure modes requires a combination of testing, explain-plan review, and production-like load validation. Build unit tests that assert row counts and sample aggregates, run EXPLAIN ANALYZE on representative data to reveal sorts and joins that will spill, and add regression checks for query-duration and temp-space budgets in CI. Taking this approach lets us find silent correctness bugs and resource-bound failures before users notice, which is the essential next step before we dive into targeted fixes and optimization patterns.

Incorrect join conditions

When a report suddenly doubles or your OLTP query spikes tempdb usage, the root cause is often a bad SQL JOIN early in the plan — specifically a mistaken or missing join condition that silently changes result cardinality. We see this problem when joins use the wrong keys, drop to a Cartesian product, or apply predicates in the wrong place, and those errors are both correctness and performance risks. Front-load your checks: validate join condition logic during code review and CI, because a plausibly-looking result set can still be semantically wrong while costing the cluster heavily.

A frequent mistake is using the wrong columns in the ON clause or relying on implicit join behavior. Choosing a non-unique key, swapping left/right tables, or using inequality predicates where equality is intended creates duplicates or dropped rows; these issues change aggregates and foreign-key relationships in subtle ways. Moreover, some DBAs accidentally rely on WHERE filters to enforce joins, which transforms outer joins into inner joins and removes rows you expected to retain. We should treat join predicates as business logic: state them explicitly, test them, and review them like any other contract between tables.

Missing the ON clause entirely or mis-scoping predicates can produce a Cartesian product that explodes intermediate row counts and kills execution plans. For example, compare these two snippets: SELECT c.id, o.amount FROM customers c, orders o; (no join predicate) versus SELECT c.id, o.amount FROM customers c JOIN orders o ON c.id = o.customer_id; (correct join predicate). How do you detect a missing join predicate before it reaches production? Run EXPLAIN ANALYZE on representative data, check intermediate row-count estimates versus actuals, and assert expected row-count ratios in unit tests so a runaway join shows up in CI.

Outer-join predicate placement is another silent correctness trap. If you write LEFT JOIN orders o ON c.id = o.customer_id WHERE o.status = ‘completed’ you will implicitly discard rows where o is NULL, effectively turning the LEFT JOIN into an INNER JOIN. Move selective conditions into the ON clause when their purpose is to match rows (ON c.id = o.customer_id AND o.status = ‘completed’), or explicitly test for NULL to preserve unmatched rows (WHERE o.customer_id IS NULL). This distinction changes both the semantic meaning and the optimizer’s plan shape, so place predicates intentionally.

NULLs, collations, and type mismatches also break join logic quietly. Joining on varchar columns with differing collations or on numeric vs string types can cause non-matches or implicit conversions that prevent index use. When NULL should represent an actual key value, equating NULLs requires COALESCE or database-specific operators (for example, IS NOT DISTINCT FROM) to express intent. Use casting and explicit collation settings where necessary, but be mindful that wrapping join columns in functions can inhibit index seek operations and harm performance.

Operational practices reduce risk: assert row counts and sample aggregates in your test suite, add targeted EXPLAIN checks in CI, and prefer EXISTS or semi-joins for existence checks instead of broad joins that duplicate rows. Avoid using DISTINCT to mask duplicates — that hides the bug rather than fixes the join condition. We should also treat foreign-key constraints and selective indexes as guards: when schema and stats reflect real cardinality, the optimizer is more likely to choose safe plans. Next, we’ll examine how window-frame mistakes compound these join-level errors and create even subtler correctness regressions.

Wrong join types and NULLs

Building on this foundation, the most insidious SQL JOIN bugs come from choosing the wrong join type and mishandling NULLs early in the plan, because they silently change result sets while leaving queries superficially plausible. SQL JOIN and NULL behavior should be front-of-mind when you review joins: an INNER JOIN, LEFT JOIN, or RIGHT JOIN is not interchangeable without a deliberate change in semantics. When you swap join types or ignore NULL semantics, you risk dropping expected rows or creating hidden duplicates that skew aggregates and downstream logic.

Start by treating join direction as business logic. An INNER JOIN expresses a strict match requirement: rows that don’t have matches are excluded. An outer join (LEFT/RIGHT/FULL) expresses preservation of the driving table and introduces NULLs for the missing side. When you confuse these—by using an INNER JOIN where the business needs preservation or vice versa—you change whether NULL placeholder rows exist and how aggregations behave. This is both a correctness and a performance concern because the optimizer’s plan and cardinality estimates differ dramatically between an inner and an outer join.

A common pitfall is filtering on the outer side in the WHERE clause and unintentionally converting an outer join into an inner join. For example, consider:

SELECT c.id, o.amount

FROM customers c

LEFT JOIN orders o ON c.id = o.customer_id

WHERE o.status = 'completed';

Here the WHERE filter removes rows where o is NULL, which negates the LEFT JOIN. Move the predicate into the ON clause or explicitly allow NULLs: ON c.id = o.customer_id AND o.status = ‘completed’, or use WHERE o.customer_id IS NULL to detect unmatched customers. This small placement change preserves the intended outer-join semantics and avoids surprising row loss.

NULL equality semantics are another subtle source of bugs. NULL is not equal to NULL under standard SQL, so joining nullable key columns will fail to match rows that you expect to pair. You can make intent explicit with COALESCE when you have a safe sentinel value, or with dialect-specific operators like IS NOT DISTINCT FROM where supported. For example:

-- safe when a sentinel value is acceptable

ON COALESCE(a.key, -1) = COALESCE(b.key, -1)

-- PostgreSQL: exact null-equality semantics

ON a.key IS NOT DISTINCT FROM b.key

Keep in mind that wrapping join keys in functions like COALESCE can prevent index seeks and force full scans, so balance correctness with performance.

When function-wrapping hurts performance, prefer schema or index-level fixes. Add a persisted computed column that normalizes NULLs, index that column, and join on it, or enforce NOT NULL with a domain-level sentinel where it makes sense. These approaches preserve indexability and keep joins efficient while making NULL intent explicit. Also consider using semi-joins (EXISTS) for existence checks instead of broad joins that duplicate rows and require extra deduplication.

NULLs also change aggregate outcomes: COUNT(col) ignores NULLs while COUNT() counts rows, and SUM/AVG propagate NULL unless you coalesce. If an outer join introduces NULL placeholders, your COUNTS and SUMs will silently differ. For example, COUNT(o.id) after a LEFT JOIN will not count unmatched rows; if you intended to count customers regardless of orders, use COUNT() or COUNT(DISTINCT c.id) as appropriate. Validate these expectations in tests, because using DISTINCT or COUNT to hide duplicates masks the underlying join problem rather than fixing it.

How do you detect these issues before they reach production? Add unit tests that assert row counts and representative aggregates with both matched and unmatched cases, include EXPLAIN ANALYZE checks for plan shape and intermediate row counts, and add a CI assertion that flags WHERE clauses referencing outer-table columns after an outer join. By making NULL-handling and join direction explicit in code, tests, and schema, we reduce the quiet correctness bugs that later balloon into performance incidents.

Taking this concept further, the next area to inspect is how window functions interact with outer joins and NULL placeholders: mispartitioned frames and global sorts can compound the correctness effects we just discussed. Preserve join intent, normalize NULLs where appropriate, and validate aggregates so window-frame mistakes don’t amplify hidden errors.

Window partitioning and framing mistakes

Window partitioning and framing mistakes are where correctness and performance quietly collide: a misplaced PARTITION BY or an unbounded frame can silently change aggregates while forcing the engine into massive sorts and memory spills. In the first 100 words we need to call out the core problems you’ll see in production—mispartitioned groups, nondeterministic ORDER BYs, and frames that span the entire table—because these directly affect both the meaning of results and query resource usage. If you want predictable results and predictable latency, start by treating partitioning and framing as explicit design choices, not defaults you’ll rely on to behave sensibly under scale.

A common error is mispartitioning the data so window calculations cross logical groups. When you omit PARTITION BY or use the wrong key, values meant to be grouped by customer, session, or tenant bleed into each other; aggregates and ranking functions return plausible but incorrect values. For example, ROW_NUMBER() OVER (ORDER BY ts DESC) ranks across the whole dataset, whereas ROW_NUMBER() OVER (PARTITION BY user_id ORDER BY ts DESC) gives you per-user recency. If you change the partition key later (for example from user_id to account_id) without a schema-aware review, downstream deduplication or SLA calculations will silently change. Always name the partition key intentionally and include composite keys when the business identity requires it (PARTITION BY user_id, device_id) rather than relying on implicit uniqueness.

Frame semantics are the second frequent trap: RANGE vs ROWS, bounded vs unbounded, and the default frame for some functions can yield surprising peer-group behavior. RANGE BETWEEN UNBOUNDED PRECEDING AND CURRENT ROW groups all peers with equal ORDER BY values, which is handy for numeric offsets but dangerous for timestamps or floating-point values where peers are rare or accidental. If you need a sliding window over a fixed number of rows, prefer ROWS BETWEEN 2 PRECEDING AND CURRENT ROW; if you need a time-based window, express it explicitly and be mindful of timezone/fractional precision. For example:

-- unintended: groups equal timestamps as peers

SUM(amount) OVER (PARTITION BY user_id ORDER BY ts RANGE BETWEEN UNBOUNDED PRECEDING AND CURRENT ROW)

-- intended: deterministic 24-hour lookback (Postgres syntax example)

SUM(amount) OVER (PARTITION BY user_id ORDER BY ts RANGE BETWEEN INTERVAL '24 hours' PRECEDING AND CURRENT ROW)

An often-overlooked operational mistake is leaving ORDER BY nondeterministic inside the window, which makes ROW_NUMBER(), RANK(), and similar functions produce flaky results on ties. If you use ROW_NUMBER() to pick the “latest” row, always include a deterministic tiebreaker (for example, a surrogate id): ROW_NUMBER() OVER (PARTITION BY user_id ORDER BY ts DESC, id DESC). Choosing RANK() vs ROW_NUMBER() also matters: RANK() preserves ties and can produce duplicate positions that break downstream uniqueness assumptions. When you need stable deduplication, prefer ROW_NUMBER with a well-defined tie-breaker so your tests and production behavior match exactly.

Performance-wise, large or skewed partitions force the engine into heavy sorts and can spill to disk. You’ll see this in EXPLAIN ANALYZE as large sort nodes, unexpectedly high tempdb/temporary space usage, or huge actual vs estimated row differences. Mitigate by pre-aggregating where feasible, adding indexes that match your PARTITION BY/ORDER BY pattern to allow index-based ordering, bounding frames to reduce sort windows, or using streaming approximations for real-time dashboards. In testing, generate skewed datasets and assert both functional outputs and resource budgets; that combination of deterministic partitioning, explicit frame definitions, and production-like load tests keeps window functions correct and performant as you scale.

Performance impacts and execution plans

Building on this foundation, the fastest way a correct-looking query becomes a production disaster is when the execution plan silently amplifies intermediate rows and resource usage. When you care about query performance and predictable latency, the optimizer’s chosen execution plan is the single most important artifact to inspect first. How do you tell when a plan is the culprit? Run EXPLAIN ANALYZE (or your engine’s equivalent) against representative data and compare estimated rows to actual rows — large divergences point directly at bad cardinality estimates that drive poor join orders, nested-loop choices, or massive sorts.

Cardinality estimates steer join selection and operator ordering, so a small estimation error can cascade into major costs. If the optimizer thinks a filter will reduce a table to 10 rows but it’s actually 100k, it may pick a nested-loop join that multiplies cost; conversely, overestimating selectivity can force an unnecessary hash or merge join with a big hash-build or sort. To diagnose this, locate plan nodes where actual_rows >> estimated_rows and trace back to stale statistics, missing histograms, or correlated columns the planner can’t model. Update statistics, add extended stats for correlated keys, or rewrite predicates so the planner sees the true selectivity before you try other interventions.

Join algorithm and sort behavior are the mechanics behind plan pathologies, and window functions introduce additional pressure because they often require partitioning and ordering. Nested loops excel when the inner side is small and indexed; hash joins are good for large, unsorted inputs but allocate memory for hash tables; merge joins require presorted streams. Window functions like ROW_NUMBER() OVER (PARTITION BY user_id ORDER BY ts DESC) will usually force a sort or a shuffle unless you provide an index that supplies the required ordering. Create covering indexes that match your PARTITION BY/ORDER BY pattern to avoid full-table sorts, but weigh index maintenance costs against read performance.

Diagnosing plan problems requires targeted queries and micro-rewrites. Start with EXPLAIN ANALYZE, identify heavy sort and materialize nodes, and inspect temp-space/spill metrics — spills to disk are the red flag for resource exhaustion. If you find an expensive sort caused by a window frame, try bounding the frame (ROWS vs RANGE) or add a deterministic tie-breaker to ORDER BY to make plans stable. For existence checks or semijoins, replace broad JOINs with EXISTS or use LATERAL to limit the optimizer’s exposure to large intermediate sets; this often reduces duplicated rows early and improves query performance without changing semantics.

When plan changes are persistent or nondeterministic, you can use plan-stability tools judiciously. Force-plan hints or plan baselines can stop regressions, but they lock you into a path that may become suboptimal as data evolves, so prefer schema and statistics fixes first. Materialize intermediate results with temporary tables or use a MATERIALIZED CTE (when supported) to break a complex plan into predictable stages; this sacrifices some optimizer freedom but gives you explicit control over sort and join order for heavy aggregations or window computations. Also schedule regular ANALYZE runs and increase stats sampling for skewed or long-tail distributions so the planner has accurate inputs.

Operationalize plan review into CI and load testing so query performance regressions surface early. Capture representative EXPLAIN plans in tests, assert estimated-vs-actual row ratios remain within budget, and add regression budgets for duration and temp-space for heavyweight queries that use SQL JOINs and window functions. By combining explain-plan inspection, targeted indexes that support partitioning and ordering, and proven rewrites (EXISTS vs JOIN, bounded frames, materialization), we keep query performance predictable and avoid the subtle plan pathologies that otherwise show up only under production scale — next, we’ll examine concrete rewrites that fix the most common join-and-window plan failures.

Fixes: indexing, rewrite, tests

Building on this foundation, the fastest way to stop silent correctness and cost regressions is to intervene at three levels that work together: schema and indexing, targeted query rewrites, and disciplined tests that assert both meaning and resource budgets. We often see a partial fix—an index added without a rewrite, or tests that check correctness but not temp-space—that fails under scale; combining these approaches prevents that. How do you prioritize fixes when a query both returns wrong numbers and spills to disk? Start by isolating the correctness issue, then use indexing and rewrite strategies to make the plan predictable, and lock that behavior with tests that run in CI and in a production-like environment.

First, treat indexing as a correctness-and-performance lever, not a cosmetic optimization. If a window function or a join pattern forces a global sort, create a covering index that supplies the PARTITION BY and ORDER BY ordering so the engine can stream results instead of sorting: for example, CREATE INDEX ON events (user_id, ts DESC) supports ROW_NUMBER() OVER (PARTITION BY user_id ORDER BY ts DESC) and often removes the large sort node. When NULL normalization is required to express join intent, add a persisted computed column that coalesces NULLs and index that column rather than wrapping join keys in functions at query time; this preserves seekability while expressing the correct semantics. We focus indexing on the operator shape the optimizer needs (seek + index-order) rather than blindly indexing every filter column, because excessive indexes raise write costs and maintenance overhead.

Second, rewrite queries to constrain intermediate cardinality and make semantics explicit. Replace broad JOINs with EXISTS or semijoins when you only need membership; this prevents unintended duplication from joining a many-side table. When you must preserve outer-join semantics but filter on the right table, move predicates into the ON clause or use IS NOT DISTINCT FROM/COALESCE patterns that preserve NULL intent while remaining index-friendly. For window functions, bound frames to the minimum necessary scope (ROWS BETWEEN 5 PRECEDING AND CURRENT ROW for fixed-row windows or an explicit RANGE interval for time windows) and add deterministic tie-breakers in ORDER BY (for example, ORDER BY ts DESC, id DESC) so ROW_NUMBER() behaves reproducibly in tests and production. When the optimizer still picks a bad plan, materialize the heavy intermediate step with a temporary table or a materialized CTE to force predictable sorting and join order.

Third, make tests enforce both correctness and resource expectations. Unit tests should assert row counts, representative aggregates, and specific sample rows for boundary cases (null keys, tie values, unmatched outer rows). Add an EXPLAIN/EXPLAIN ANALYZE gate to CI that captures estimated-vs-actual row ratios for key plan nodes and fails when divergence exceeds a threshold; for example, assert that actual_rows / estimated_rows < 10 for join and sort nodes you care about. Include budget tests that fail CI if a query spills to disk, exceeds a temp-space quota, or regresses median/90th latency beyond a configured threshold when run against a representative dataset or a synthetic skew that mirrors production.

We must combine these levers deliberately: index choices reduce sort pressure, rewrites control cardinality and semantics, and tests lock in both functional and operational contracts. When you change schema or add an index, update your tests to assert the new plan properties so future refactors can’t silently reintroduce regressions. Use lightweight plan-stability tools sparingly; prefer schema and statistics fixes first because hints or forced plans can degrade as data evolves and make future maintenance riskier.

Taking these approaches together turns reactive firefighting into reproducible engineering work. By aligning indexing with PARTITION BY/ORDER BY patterns, rewriting queries to minimize intermediate rows and make semantics explicit, and codifying performance and correctness expectations in CI, we ensure SQL JOINs and window function logic remain correct and predictable under production scale — next, we’ll apply these patterns to concrete rewrites that commonly break or save production workloads.