Why Tokenization Matters

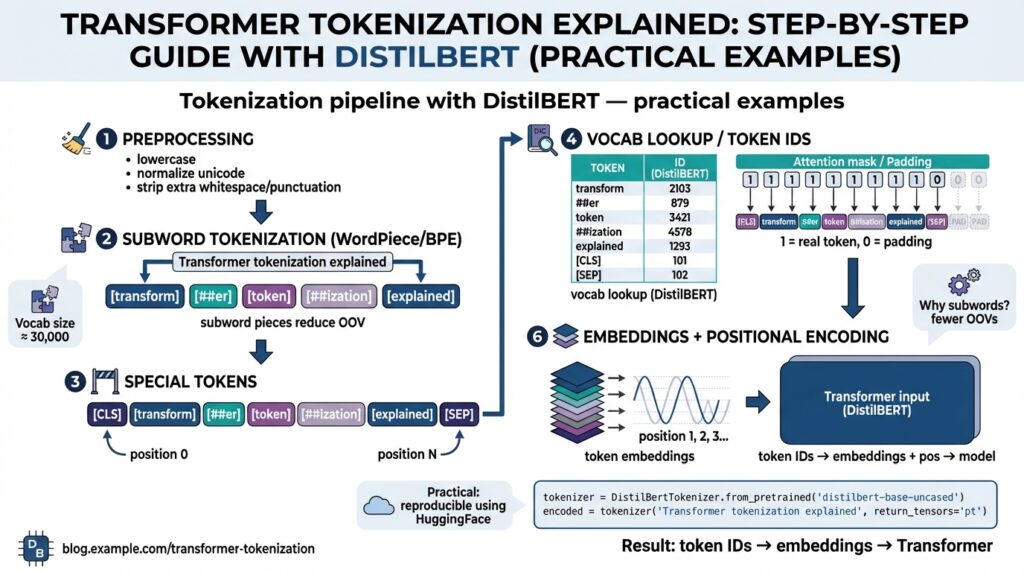

Building on the foundations of transformer architecture, tokenization is the essential preprocessing step that determines whether your inputs become meaningful signals or noisy garbage for the model. Tokenization converts raw text into the discrete IDs the model can embed and attend over, and small choices here—vocabulary, subword granularity, special tokens—change model behavior, performance, and interpretability. If you treat tokenization as an afterthought, you’ll spend more time debugging label misalignment, leaking tokens across examples, or chasing apparent model failures that are really preprocessing bugs. We’ll unpack why transformer tokenization deserves design attention in production systems and experiments.

At a technical level, tokenization shapes the model’s input space: it decides token boundaries, maps text to integers, and defines the embedding lookup that the transformer uses at every layer. Subword tokenization (methods like WordPiece, BPE, or Unigram) breaks unknown words into smaller, frequent subunits so the model can represent rare morphology without an enormous vocabulary. The tokenizer also injects control tokens—CLS, SEP, PAD—and produces attention masks and token type IDs that affect positional alignment and batching. Because these outputs flow directly into the transformer’s embedding matrix and attention mechanism, tokenizer design becomes a capacity and latency trade-off you must manage.

Tokenization matters for model capacity and generalization. A huge, word-level vocabulary increases the embedding matrix size—raising memory use and inference cost—while overly aggressive subword splitting increases sequence length, which drives O(n^2) attention costs. For DistilBERT-style distilled transformers we often prefer a compact vocabulary and sensible subword splits to balance embedding memory and attention complexity; that keeps latency down without sacrificing linguistic coverage. Practically, this means we tune vocabulary size and training tokenization rules to match the domain: legal text, code, biomedical notes, or chat logs each benefit from different subword granularity.

Consider a real example to make this concrete. Suppose we tokenize the sentence “transformer tokenization matters” with a WordPiece-like tokenizer. The tokenizer may output tokens like [“transform”, “##er”, “token”, “##ization”, “matter”, “##s”] and then map those to IDs which the model embeds. In code, using Hugging Face tokenizers the pattern looks like:

from transformers import AutoTokenizer

tok = AutoTokenizer.from_pretrained("distilbert-base-uncased")

ids = tok.encode("transformer tokenization matters")

print(tok.convert_ids_to_tokens(ids))

This shows how subword tokenization lets the model reuse learned pieces (“transform”, “token”) rather than memorizing every inflection, which improves sample efficiency and robustness to unseen words.

Tokenization also directly affects downstream tasks and evaluation. Named entity recognition, span extraction, and QA require that you map token-level predictions back to original character offsets; misaligned subwords will produce off-by-one errors or broken spans during postprocessing. How do you map model logits to character spans reliably? We recommend storing token-to-char offset maps during tokenization and designing loss functions and evaluation scripts that operate at the character or canonicalized-span level. This makes failure modes visible in error analysis and prevents misattributing performance drops to the model when they stem from alignment bugs.

Finally, tokenization choices shape retraining, transfer learning, and inference pipelines. When you fine-tune DistilBERT on a domain corpus, reusing its original tokenizer usually helps stability, but vocabulary extension or domain-specific tokenizers can improve performance if you retrain embeddings. In production, pay attention to deterministic tokenization (same input → same tokens), consistent casing, and how you handle unknown characters, because these details determine reproducibility and debuggability. Taking tokenization seriously up front reduces surprises downstream and yields cleaner ablations when we change model architecture or data.

Taking this concept further, we’ll walk through a hands-on DistilBERT tokenization walkthrough next: token ID layouts, special-token handling, padding/truncation strategies, and detokenization for human-readable outputs. That step-by-step example will show how to instrument tokenizers in your training loop and inference service so you can measure the practical impact of tokenization on both metrics and latency.

Subword Methods: WordPiece Explained

Building on this foundation, WordPiece is the subword tokenization approach you’ll most often encounter in BERT-derived models, and understanding it changes how you design tokenizers for production. In practice, WordPiece shapes the tokenizer’s vocabulary and split behavior in ways that directly affect embedding size, sequence length, and downstream span alignment. How does WordPiece decide splits and why does that matter for models like DistilBERT? Asking this upfront steers our design choices: vocabulary size, special-token handling, and whether to extend or retrain embeddings.

At its core, WordPiece trains a vocabulary by maximizing the likelihood of the training corpus under a subword language model rather than performing blind frequency merges. Start from characters and iteratively add subword units that improve corpus likelihood; each unit reduces the overall tokenization cost for common substrings while preserving an [UNK] fallback for truly unseen bytes. In tokenized outputs you’ll see continuation markers (for BERT-style tokenizers that use them) such as “##” to denote that a piece attaches to the previous token, e.g., “play” + “##ground” for “playground”. That continuation marker is important for reconstructing original text and mapping token logits back to character spans reliably.

Comparing algorithms clarifies when WordPiece is the right tool. Byte-Pair Encoding (BPE) greedily merges most frequent adjacent pairs, while Unigram models treat the vocabulary probabilistically and sample segmentations; WordPiece sits between these by optimizing corpus likelihood for deterministic splits. For masked language modeling and transfer learning on medium-size corpora, WordPiece often yields a compact vocabulary with robust morphological reuse, which helps models generalize without extreme sequence growth. When you need byte-level robustness (e.g., unpredictable punctuation or arbitrary UTF-8 inputs), consider byte-level BPE or a hybrid strategy instead.

There are clear operational trade-offs you must weigh when using WordPiece in production. A smaller vocabulary reduces embedding matrix size and memory pressure but increases average token count per example, which raises O(n^2) attention cost and latency; a larger vocabulary reduces sequence length but inflates parameter count and storage. Rare or domain-specific terms will be split into multiple subwords—this helps the model reuse morphology but complicates tasks like named entity recognition, where you must preserve token-to-character offsets to avoid off-by-one span errors. Measure both token length distributions and model performance when you vary vocabulary size to find the sweet spot for your domain.

Practically, instrumenting the tokenizer and embedding pipeline prevents subtle bugs. Preserve token-to-char offset maps during tokenization and use them in loss computation and evaluation scripts to ensure spans align with original text; store whether a token is a word-start (no continuation marker) so you can aggregate subword logits when predicting entity labels. If you extend a pretrained tokenizer, add tokens via tokenizer.add_tokens([…]) and then resize the model embeddings (e.g., model.resize_token_embeddings(len(tokenizer))) before fine-tuning—otherwise new IDs map to random or missing vectors. Also plan for normalization rules (case-folding, unicode normalization) and a deterministic preprocessor so identical inputs always produce identical token sequences.

To operationalize this knowledge, run controlled experiments: vary vocabulary sizes, record average tokens per sentence, and measure end-to-end latency and task metrics. We recommend logging misaligned spans and [UNK] frequency as early indicators of tokenization mismatch. Taking these steps lets us tune the tokenizer as a first-class component of the modeling pipeline and prepares us for the next walkthrough where we inspect DistilBERT’s token ID layout, special-token behavior, and concrete instrumentation patterns for training and inference.

DistilBERT Tokenizer Basics

Building on the foundation we just covered, the practical behavior of the DistilBERT tokenizer determines how raw text becomes the sequence of token IDs and attention signals your model actually sees. If you’ve ever wondered how to go from a sentence to a batch-ready tensor for DistilBERT, that transformation hinges on a few predictable outputs: input_ids, attention_mask, and a set of special-token IDs you can query from the tokenizer. How do these pieces interact during training and inference, and what should you monitor to avoid silent preprocessing bugs?

The tokenizer returns concrete artifacts you will use everywhere in your pipeline. The primary arrays are input_ids (the integer IDs mapped from subword tokens) and attention_mask (1 for real tokens, 0 for padding); many implementations also can return offset mappings that map each token back to character spans. You should call the tokenizer with padding and truncation parameters when producing batches (for example, tokenizer(texts, padding=True, truncation=True, return_tensors=’pt’, return_offsets_mapping=True)). These outputs let you construct masked-language-model (MLM) labels, compute attention windows, and preserve alignment for span-based tasks without reprocessing raw strings at runtime.

Special-token IDs are a small but critical API surface to inspect programmatically rather than hard-code. Query tokenizer.cls_token_id, sep_token_id, pad_token_id, mask_token_id, and unk_token_id so you always build inputs and label masks deterministically across code paths. For masked-language training you’ll set labels to -100 on pad tokens and sometimes on special tokens to avoid spurious loss; for sequence-pair inputs you’ll add SEP tokens explicitly according to the tokenizer’s convention. Knowing exact token IDs prevents off-by-one errors when you build position-dependent features or slice logits for evaluation.

Subword boundaries and token-to-character offsets determine how you map model logits back to human text. DistilBERT tokenizer uses a WordPiece-like subword scheme we discussed earlier, which means many words split into multiple tokens and may carry continuation markers. When you need token-level predictions (NER, QA), use return_offsets_mapping or tokenizer.word_ids() to group subword logits into word-level predictions by aggregating probabilities—pick the max, first-subtoken, or mean strategy depending on your labeling scheme. Instrumenting this mapping in your training loop makes error analysis straightforward and avoids attributing alignment mistakes to model capacity.

Batching and padding strategy directly affect latency and memory. Choose dynamic padding (pad to the longest sequence in the batch) for variable-length inference to reduce wasted compute, and pick a sensible max_length for training that covers the 90–99th percentile of your corpus token lengths to balance coverage and attention cost. Remember that attention complexity grows with sequence length, so measure average tokens per sample after tokenization and log distribution metrics; these numbers often drive the difference between acceptable and unusable inference latency in production.

Detokenization and human-readable outputs require deliberate handling of special tokens and subword markers. Use tokenizer.decode(ids, skip_special_tokens=True) for display, but when reconstructing exact original text for span evaluation prefer offsets to splice characters from the source string; simple join-and-strip approaches can break whitespace and punctuation. If you extend the tokenizer with domain-specific tokens, call model.resize_token_embeddings(len(tokenizer)) before fine-tuning so new token IDs map to initialized vectors that you can then train.

These practical tips make the DistilBERT tokenizer predictable and auditable in your pipeline, reducing mysterious metric drops caused by preprocessing drift. Next we’ll inspect token ID layout and special-token behavior in a concrete walkthrough so you can instrument tokenizers, trace token-to-char maps in your training loop, and measure the tokenization effects on both accuracy and latency.

Special Tokens and IDs

Special tokens and token IDs are the small API surface that cause outsized debugging pain when they’re wrong; treat them like part of your contract with the model. We often focus on subword splits and vocabulary, but the reserved IDs (CLS, SEP, PAD, MASK, UNK) determine how inputs map to embeddings and how downstream code slices logits. If you hard-code numeric IDs or assume positions, subtle off-by-one or loss-masking bugs appear only after hours of training, so we recommend explicit assertions and instrumentation early in the pipeline.

Always query the tokenizer for canonical IDs instead of embedding magic numbers. Call tokenizer.cls_token_id, tokenizer.sep_token_id, tokenizer.pad_token_id, tokenizer.mask_token_id and tokenizer.unk_token_id at process startup and store them in a small constants object you ship with your model. This keeps your data loader, augmentation scripts, and inference service in agreement; when you extend a vocabulary or swap lower/upper-casing rules, changing the tokenizer becomes a single source-of-truth update rather than a scavenger hunt across codebases.

Understand how the IDs are placed in the sequence for different input shapes. For a single sequence you’ll typically see [CLS] … [SEP], and for sequence-pair inputs the pattern becomes [CLS] A [SEP] B [SEP], where each bracketed item is a single token ID. Construct input_ids programmatically using tokenizer.encode_plus (or tokenizer(…)) with return_tensors to avoid manual concatenation; that preserves the tokenizer’s SEP/CLS conventions and continuation markers so token-to-char offsets remain valid for span tasks.

How do you treat those IDs during loss computation and masking? For classification and QA, set labels to ignore_index (commonly -100) on PAD and often on special tokens so CrossEntropyLoss ignores them. For masked language modeling we substitute some input_ids with mask_token_id and compute loss only for the masked positions; never compute MLM loss on CLS/SEP/PAD. This prevents the model from learning spurious patterns tied to control tokens and keeps gradients focused on real linguistic signal.

Be explicit about token type IDs and attention masks because model implementations differ. Many tokenizers still return token_type_ids for compatibility; however, DistilBERT’s distilled architecture omits token-type embeddings at runtime, so token_type_ids may be ignored by the model even if the tokenizer produces them. Check model.config or the model’s forward signature in your framework and log whether token_type_ids are consumed; if they are unused, drop them from serialized inference payloads to reduce I/O and avoid confusion.

Mapping special token IDs back to human-readable text requires care when detokenizing and evaluating spans. Use tokenizer.decode(ids, skip_special_tokens=True) for display, but for exact span reconstruction prefer return_offsets_mapping so you can splice characters from the original string; this avoids whitespace and punctuation normalization differences introduced by decode. When aggregating subword logits into a word-level label, collapse subtoken probabilities by first-subtoken or max-over-subtokens depending on whether your annotation scheme labels whole words or pieces.

Instrument and monitor special-token frequency as part of your tokenization telemetry. Log counts of mask_token_id, pad_token_id, and unk_token_id per corpus shard and fail fast if you see unexpected distributions (for example, many unk tokens indicates a vocabulary mismatch). We also add small CI checks that assert tokenizer.pad_token_id is not None and that model.config.vocab_size == len(tokenizer); these simple guards catch many deployment-time mismatches when using DistilBERT and custom tokenizers. Taking these steps makes special tokens and token IDs a reliable, auditable part of your training and inference pipelines rather than a recurring source of production surprises.

Creating Input Tensors

Getting from tokenized text to a batch the model can consume is more than an API call; it’s where tokenization meets linear algebra and production constraints. When you prepare input tensors for DistilBERT, the immediate goal is a compact, deterministic representation: input_ids, attention_mask, and any optional arrays (offset mappings, token_type_ids) shaped as [batch_size, seq_len]. We care about reproducibility and performance here because small differences—padding side, dtype, device placement—change memory footprints and runtime behavior across training and inference.

Data types and tensor shape are the first correctness checks you should add in your pipeline. Create input_ids as integer tensors (torch.long / int64) because embedding lookups require integer indices; use attention_mask as the same integer dtype or boolean depending on your framework, but be consistent across training and inference. Ensure tensors are contiguous in memory and pinned when using non-blocking transfers to CUDA to minimize copy overhead. Move tensors to the model device early (for example, batch = {k: v.to(device) for k,v in batch.items()}), and assert shapes with a small runtime check (batch[‘input_ids’].shape == (B, L)) so downstream operations never silently misalign.

Padding and truncation strategy directly affect both latency and accuracy, so choose them deliberately. Use dynamic padding (pad to longest sequence in the batch) during inference to reduce wasted compute, and set a fixed max_length during training chosen from the 90–99th percentile of your corpus token lengths to cap attention cost. Respect pad_side (‘right’ versus ‘left’) to match model expectations and downstream span alignment; inconsistent pad_side causes off-by-one errors in span-based tasks. For convenience and correctness, use a collator (for example, transformers’ DataCollatorWithPadding) to centralize padding behavior and produce consistent input tensors across data loaders.

Batches should be constructed with an explicit collate function rather than relying on the tokenizer to return tensors for individual items. Implement a collate_fn that accepts a list of raw tokenized dicts and returns a batched dict of torch tensors; this lets you control padding, padding token id, and device placement in one place. Example pattern:

def collate_fn(examples):

batch = tokenizer(examples, padding=True, truncation=True, return_tensors='pt', return_attention_mask=True)

batch = {k: v.to(device) for k, v in batch.items()}

return batch

Putting the batch construction logic here avoids duplicated assumptions across training, eval, and inference code paths and keeps your tokenization telemetry consistent.

How do you map labels to these input tensors for different tasks? For masked language modeling, replace selected input_ids with mask_token_id in the input tensors while keeping label tensors containing the original token ids and setting ignore_index (commonly -100) for PAD and special tokens so the loss ignores them. For token-level tasks like NER or QA, use the tokenizer’s return_offsets_mapping or word_ids() to align subword logits back to character spans, then collapse subtoken logits (first-subtoken, max, or mean) to produce word-level predictions; set labels to -100 for pad positions and, where appropriate, for continuation subtokens if your annotation scheme labels whole words. Instrument these mappings in the collate stage so label creation is deterministic and reproducible.

Finally, plan for edge cases and operational ergonomics rather than ad hoc fixes. For long documents implement sliding-window chunking with overlapping strides so each input tensor fits max_length while preserving context for span tasks; monitor unk_token_id frequency and pad token counts as tokenization telemetry to detect vocabulary mismatches early. Remember that DistilBERT may ignore token_type_ids in its forward pass—query model.config or inspect the forward signature and drop unused fields to shrink serialized payloads. With these patterns in place we keep tokenization tightly coupled to tensor creation, making input tensors reliable, auditable, and performant as we move into the token ID layout and special-token instrumentation covered next.

Python Examples: Tokenize And Decode

Building on this foundation, getting tokenization right in code is about more than calling a library — it’s about producing deterministic input_ids and reversible outputs you can instrument and trust. We load a DistilBERT tokenizer once in your service and treat its outputs (input_ids, attention_mask, offsets) as part of the contract between preprocessing and model inference. Small differences in padding, truncation, or skipping offsets lead to subtle span misalignment or evaluation drift, so we recommend asserting key IDs at startup. How do you reliably tokenize and decode in Python while preserving exact spans and human-readable outputs?

Start with a single-shot example that shows the important return artifacts and their types. The tokenizer returns integer input_ids and attention_mask arrays and can also return offset mappings that map tokens to character spans; those offsets are essential for precise span reconstruction. Example pattern:

from transformers import AutoTokenizer

tok = AutoTokenizer.from_pretrained("distilbert-base-uncased")

out = tok("Transformers tokenize and decode correctly.", return_offsets_mapping=True)

print(out['input_ids'])

print(out['attention_mask'])

print(out['offset_mapping'])

This shows how to inspect token IDs and offsets programmatically; treat offset_mapping as your canonical source for mapping logits back to original characters rather than relying on text-based detokenization.

When you tokenize batches for training or inference, choose padding and truncation consistently and prefer return_tensors when you want immediate tensors. Dynamic padding (pad to longest in the batch) reduces wasted compute at inference time while fixed max_length during training stabilizes memory. Use the tokenizer inside a collate function so you control pad_side, pad_token_id, and device placement centrally:

batch = tokenizer(texts, padding=True, truncation=True, return_tensors='pt', return_attention_mask=True)

# move to device and assert shapes

batch = {k: v.to(device) for k, v in batch.items()}

Decoding back to readable text requires you to pick the right tool for the job: tokenizer.decode(ids, skip_special_tokens=True) is fine for display, but it may normalize whitespace and drop punctuation in ways that break character-accurate span evaluation. If you need exact spans for QA or NER, splice text using offset_mapping instead of decode. For example, reconstruct an answer span by slicing the original string using offsets[start_token][0]:offset[end_token][1], which preserves original casing, whitespace, and punctuation.

Aggregating subtoken logits into word-level predictions is another common need for token classification tasks. Continuation subtokens (WordPiece markers) mean one word can produce several logits; a robust pattern is to map tokenizer.word_ids() to group subtokens, then reduce within each group using first-subtoken, max, or mean depending on your labeling scheme. Example:

word_ids = tok.word_ids(batch_index)

# collect logits per word: for each unique word_id pick logits[first_subtoken]

Choose first-subtoken when your annotations align to whole words; choose max when you want the most confident piece to drive the label.

Finally, handle special cases proactively so decode/tokenize round-trips remain reliable in production. Assert tokenizer.cls_token_id, pad_token_id, and unk_token_id at startup; log unk_token frequency and average tokens-per-sentence as telemetry. If you add domain tokens, call tokenizer.add_tokens([…]) and then model.resize_token_embeddings(len(tokenizer)) before fine-tuning so new IDs have valid embeddings. These small guards prevent silent failures during training and keep tokenization auditable as we move into token ID layouts and instrumentation.