Why normalization matters

Database normalization sits at the center of reliable relational design because it removes the kinds of redundancy that quietly wreck systems over time. You probably recognize the symptoms: addresses updated in one table but not another, reports that count the same customer twice, or cascading delete surprises during a routine maintenance window. By front-loading the goal—minimize redundant storage and express dependencies clearly—you reduce update, insert, and delete anomalies that otherwise force ad-hoc fixes and fragile application logic.

Building on this foundation, normalization gives you predictable data behavior and clearer reasoning about schema changes. At its core the process encodes functional dependencies (what determines what) into table structure so you, as a developer or DBA, can reason about transactions and constraints rather than guess at implicit rules. This matters for both correctness and collaboration: when your schema documents the invariants, tests and migrations become simpler, and new team members can understand data flows quickly. In practice, that means fewer emergency rollbacks, fewer rescue scripts, and faster, safer deployments.

Consider a concrete e-commerce example where orders carry customer address fields in the orders table. That design seems convenient, but it creates an update anomaly: changing a customer’s address requires updating every historical order row that replicated that address. Here’s a minimal illustration of the problem:

-- Bad: customer address duplicated per order

orders(order_id, customer_id, customer_name, customer_address, item_id, qty)

When you normalize by splitting customers into their own table and referencing them with a foreign key, updates become a single-row operation and historical integrity is explicit. This change reduces storage for repeated data, eliminates inconsistent address versions, and lets you add address validation or audit columns in one place without touching order ingestion pipelines.

Normalization is not only about correctness; it’s about predictable performance trade-offs and operational flexibility. Normalized schemas increase the number of joins in some read paths, so you should measure where join cost becomes a real issue versus where redundancy introduces data-commit complexity. When should you denormalize? Denormalize for read-heavy analytical tables, latency-critical hot-paths, or when materialized views/cache layers are more maintainable than transactional denormalization. Use indexes, partial indexes, and materialized views to get the best of both worlds: normalized OLTP for writes and efficient, curated denormalized projections for reads.

Operationally, normalized schemas simplify migrations and testing because each table has a single responsibility and a narrow set of constraints. Foreign keys and unique constraints enforce invariants that would otherwise be buried in application code; that enforcement helps you catch bugs earlier in CI and reduces subtle production drift. Backups and incremental replication also behave more predictably when the same piece of truth exists in one place, which simplifies disaster recovery playbooks and reduces RPO/RTO complexity during outages.

If you’re refactoring a messy schema, approach normalization incrementally: identify the highest-risk anomalies, extract small child tables, backfill data, and switch write paths via dual-write or shadow-write strategies. We often recommend adding constraints and foreign keys only after backfills and tests are green to avoid blocking live traffic. Small, reversible migrations with comprehensive tests and metrics let you validate both correctness and performance before making a final cutover, limiting blast radius and giving you rollback options.

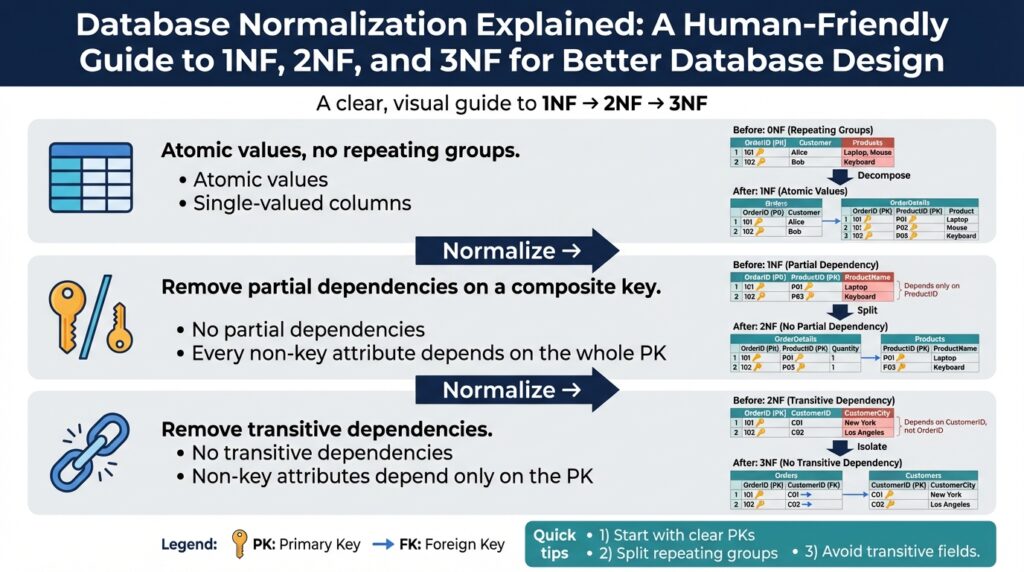

Ultimately, treating schema design as a first-class engineering concern pays dividends across development velocity, data quality, and operational resilience. When you normalize thoughtfully, you lower the cognitive load for future changes, reduce the need for brittle application-level hacks, and create a platform where both transactional integrity and efficient reporting can coexist. In the next section we’ll apply these principles to practical 1NF, 2NF, and 3NF transformations so you can see step-by-step how to move from messy duplication to a maintainable, tested schema.

Key terms and concepts

Database normalization is a set of concepts and vocabulary you need to use fluently to reason about schema changes and avoid subtle data bugs. To get practical value from 1NF, 2NF, and 3NF you must be comfortable with a small glossary: relation (table), tuple (row), attribute (column), atomicity (indivisible values), keys, functional dependencies, and integrity constraints. We’ll define each term in the context of real schemas so you can spot which invariants belong in the database and which belong in application logic.

Start with the essentials: a relation is simply a named set of tuples with the same attributes, and an attribute must be atomic for 1NF—no repeating groups or nested lists. When a column stores a JSON array of phone numbers or a comma-separated list, you’ve violated atomicity; that choice pushes you away from relational guarantees and toward bespoke update logic. Converting repeating groups into child tables (one-to-many relations) both enforces atomicity and makes it straightforward to add constraints, indexes, and audit fields in the right place.

Keys are the language that tie rows to identity and invariants. A primary key uniquely identifies each tuple; candidate keys are the minimal sets of columns that could serve as a primary key; composite keys combine attributes; and surrogate keys are synthetic identifiers (auto-increment, UUID) introduced when natural keys are awkward or unstable. For example, orders(order_id PK, customer_id FK, created_at) uses order_id as a surrogate primary key and customer_id as a foreign key reference to a customers table. Choosing the right key affects joins, index design, and how you express uniqueness constraints.

Functional dependency is the concept that drives normalization: column A functionally determines column B (A -> B) when a value of A always maps to a single value of B. Think of customer_id -> customer_address as a functional dependency in a naive orders table; when that dependency exists across multiple rows, you have duplication and potential update anomalies. Distinguish full functional dependency (where the whole key determines a non-key attribute) from partial dependency (where part of a composite key determines an attribute); eliminating partial dependencies is the move from 1NF to 2NF.

Transitive dependency is the third common dependency class to watch for: A -> B and B -> C implies A -> C transitively, which introduces redundancy when C should depend on B, not directly on A. In practice, this looks like order_id -> customer_id and customer_id -> customer_region, making customer_region transitively dependent on order_id; extracting customer_region to the customers table removes that redundancy and is the essence of moving toward 3NF. Pinpointing transitive dependencies reduces update anomalies and keeps each table focused on a single responsibility.

Foreign keys and referential integrity are how we encode relationships and enforce those functional and referential dependencies at the database level. A foreign key constraint (orders.customer_id REFERENCES customers.customer_id) prevents orphan rows and documents intent for future maintainers. That said, normalization sometimes raises performance questions: maintaining many normalized joins costs read latency, so we must ask: when should you denormalize? Denormalize for read-heavy materialized views, latency-sensitive hot-paths, or when caching and projection tables provide a simpler, testable alternative.

Other core concepts you’ll use when applying normalization are constraints (unique, check), indexes, and the distinction between logical and physical design. Unique constraints enforce candidate-key semantics; check constraints capture domain rules (e.g., qty > 0); and indexes accelerate lookup paths introduced by normalization. We often apply constraints after backfilling data to avoid blocking writes during migration, and we measure index impact on write throughput before making them permanent.

These terms—atomicity, keys, functional, partial, and transitive dependencies, foreign keys, and constraints—are the toolkit you’ll use as we move from problem schemas to normalized 1NF, 2NF, and 3NF designs. In the next section we’ll apply this terminology to a concrete messy orders table and perform step-by-step transformations so you can follow the reasoning and the migration tactics we recommend.

Understanding 1NF

Building on this foundation, the first formal step in database normalization sets the baseline constraints you rely on for every subsequent refactor. In practice, 1NF is where we encode atomicity and consistent row structure into the schema so constraints, indexes, and foreign keys behave predictably. Treating database normalization as an engineering discipline means starting here: get the rows and columns right, and the higher normal forms become tractable rather than guesswork.

At its core, 1NF requires that every attribute in a relation hold atomic, indivisible values and that each tuple follows the same columnar structure. That requirement sounds simple, but it has concrete effects: it keeps functional dependencies explicit; it lets you place unique and check constraints on single columns; and it prevents update and query logic from becoming bespoke string- or array-parsing code inside application layers. When atomicity is violated, implicit invariants sneak into business logic and testing becomes fragile because the database no longer documents the shape of the data.

You’ll see 1NF violations in three common patterns: repeated columns (phone1, phone2, phone3), delimited lists (“red,green,blue”), or opaque arrays/objects stored in a single column. For example, a naive schema may look like:

-- violates atomicity: tags as comma-separated string

products(product_id PK, name, tags)

-- tags: 'open-source,cli,tooling'

Convert that repeating group into a child relation and you gain queryability, constraints, and proper indexes:

products(product_id PK, name)

product_tags(product_id FK -> products, tag_text, PRIMARY KEY(product_id, tag_text))

Modeling one-to-many relations as separate tables protects atomicity and gives us useful choices about identity and indexing. Use a composite primary key on the join table when the natural key is stable and uniquely identifies the pair; prefer a surrogate key when you need an opaque identifier for joins, audit fields, or when the natural key changes. Adding a foreign key and an index on product_tags.product_id makes joins fast and lets you enforce uniqueness (prevent duplicate tags) at the database level rather than in application code.

That said, there are pragmatic scenarios where teams intentionally relax strict atomicity. Modern RDBMSs support JSON/JSONB columns that let you store nested objects when schema flexibility or massive write throughput matters. When should you keep a JSON array instead of normalizing it? Choose JSON for attributes that are optional, sparsely queried, or genuinely schemaless (for example, third-party metadata or feature flags). Choose normalization when you need to filter, aggregate, enforce constraints, or maintain referential integrity across rows.

If you opt for JSON in a relational database, mitigate the trade-offs: add expression or partial indexes on frequently queried JSON paths, keep critical invariants mirrored in structured columns, and provide a migration path that extracts high-value fields into normal tables when query patterns stabilize. For OLTP workloads where consistency and auditability matter, normalized child tables and foreign keys remain the safer, more testable default.

When you refactor toward 1NF, do it incrementally: identify the highest-risk repeating groups, backfill new child tables from existing rows, run dual-write or shadow-write patterns during cutover, and add foreign keys only after verification to avoid write-side blocking. These tactics reduce blast radius and make it possible to measure performance impact in isolation.

Getting atomicity and row structure right is the pragmatic first step that pays dividends: it makes functional dependencies visible, lets you enforce invariants in the database, and simplifies later moves to 2NF and 3NF. In the next section we’ll examine how removing partial dependencies builds on this foundation to further reduce redundancy and clarify what belongs in each table.

Understanding 2NF

Building on this foundation of database normalization, the next practical step is about removing partial dependencies so your tables express single responsibilities. In plain terms: 2NF (Second Normal Form) applies once you have atomic rows (1NF) and your focus shifts to tables with composite primary keys. If any non-key column is determined by only part of that composite key, you have a partial dependency that invites redundancy and update anomalies. We’ll show how to find and eliminate those dependencies so your schema stays maintainable as it grows.

What exactly does 2NF require? The rule is straightforward: every non-key attribute must be fully functionally dependent on the entire primary key, not just a subset. Full functional dependency means the whole key maps to a single value for that attribute; a partial dependency means a subset of the key already fixes that value. When you identify partial dependencies, you split the table into smaller relations that map one-to-one with the determining key, which removes duplication and centralizes the truth.

A concrete example makes this clear. Imagine an enrollment table where the primary key is (student_id, course_id), but the table also stores student_name and course_title; student_name depends only on student_id and course_title only on course_id. That structure violates 2NF and duplicates student info for every enrollment. The fix is to extract students and courses into their own tables and reference them by foreign key:

-- violates 2NF

enrollments(student_id, course_id, student_name, course_title, grade)

-- normalized to 2NF

students(student_id PK, student_name, ...)

courses(course_id PK, course_title, ...)

enrollments(enrollment_id PK, student_id FK, course_id FK, grade)

We prefer explicit foreign keys after a controlled backfill so we can enforce integrity without blocking writes. When you refactor toward 2NF, extract the smallest sensible child tables first—students and courses in the example—backfill them from existing rows, and switch reads/writes in a staged cutover. Use surrogate primary keys only when natural keys are unstable or awkward; otherwise preserve natural candidate keys with unique constraints so the database continues to document invariants we rely on in tests and migrations.

Removing partial dependencies has operational trade-offs you must weigh. Normalizing to 2NF typically increases the number of joins on write and read paths and introduces additional indexes, which can affect latency and write throughput. Therefore, measure the cost: if joins become a hotspot for a latency-critical path, consider denormalized read projections, materialized views, or a cache layer rather than reintroducing duplication into the transactional schema. In many OLTP systems the clarity and consistency gained by 2NF outpace the join cost, but profiling should inform the final choice.

How do you detect partial dependencies in an existing table programmatically? One pragmatic query is to group by subsets of the composite key and count distinct values for suspected attributes; a count greater than one signals a violation. For example, grouping by student_id and counting distinct student_name across rows should return one; if not, you’ve got inconsistent or multiple names per student. Automate these checks in a migration pipeline and fail the migration early if you detect duplicates requiring manual resolution.

Taking this concept further, 2NF is a surgical move that focuses your schema on single-purpose relations and reduces duplication driven by composite keys. By extracting the determinants into their own tables and enforcing foreign keys and unique constraints after backfills, we reduce update anomalies and make subsequent moves to 3NF (removing transitive dependencies) far easier to reason about. In the next step we’ll examine how transitive dependencies hide additional redundancy and how to address them without breaking downstream consumers.

Understanding 3NF

Building on this foundation, 3NF (Third Normal Form) is the practical step that removes hidden redundancy driven by transitive dependencies and makes each table responsible for a single fact. If you’ve already applied 1NF and 2NF, 3NF refines the schema by ensuring that non-key attributes depend only on the primary key and not on other non-key columns. This front-loads invariants into the database so constraints and foreign keys capture business rules instead of ad-hoc application logic. Applying 3NF reduces update anomalies and keeps change surfaces small when domain rules evolve.

The formal rule is straightforward: a relation is in 3NF when it is in 2NF and no non-prime attribute transitively depends on the primary key. A transitive dependency means A -> B and B -> C implies A -> C, where B is a non-key column that determines C; in that case C should live in the table keyed by B, not the original relation. We define non-prime attributes as columns that are not part of any candidate key, and we remove dependencies where a non-key column determines another non-key column. This shift clarifies responsibilities: each table documents a single functional dependency set and supports concise constraints.

Look at a concrete example that builds on the orders/customer scenario you saw earlier. Suppose orders(order_id PK, customer_id, customer_region, total) stores region derived from customer_id; customer_region is transitively dependent on order_id via customer_id. That violates 3NF because region depends on a non-key column. The fix is to extract a customers table and reference it with a foreign key: customers(customer_id PK, customer_region, …); orders(order_id PK, customer_id FK, total). This change centralizes region updates and eliminates the need to update historical orders when a customer’s region changes.

How do you detect transitive dependencies in an existing schema? A pragmatic check is grouping and counting distinct values: group by the supposed determinant and count distinct dependents; if grouping by customer_id returns a single customer_region per id, but grouping by order_id shows multiple regions across orders for the same customer, you have a violation. Example SQL to probe a table might be: SELECT customer_id, COUNT(DISTINCT customer_region) FROM orders GROUP BY customer_id HAVING COUNT(DISTINCT customer_region) > 1; a low count suggests a proper determinant while a high count flags inconsistencies. Automate these scans in your migration pipeline and fail early when manual resolution is required.

When you refactor toward 3NF, take an incremental, test-driven approach. Extract the smallest sensible child tables first, backfill them from existing rows, run dual-write or shadow-write patterns to validate behavior, and only add strict foreign keys and unique constraints after verification to avoid blocking production writes. We recommend adding application-level read adapters and monitoring to ensure no regressions in latency before making the final cutover. Measure join cost and index impact as you go—3NF improves correctness but increases join surface area, so quantify the trade-offs.

3NF also affects index strategy and auditing. When you move attributes into dedicated tables, you create new join paths that benefit from well-chosen indexes and sometimes composite keys that mirror query patterns. Enforce domain invariants with unique and check constraints in the table that owns the data, not in dependent tables. For read-heavy analytic workloads where join latency dominates, consider keeping normalized transactional tables in 3NF while provisioning denormalized projections or materialized views for queries; this keeps OLTP correctness and reporting performance separated.

Taken together, 3NF is less about abstract purity and more about placing each invariant where it can be enforced, audited, and evolved with minimal blast radius. By removing transitive dependencies you make schemas easier to reason about, easier to test, and cheaper to change. In the next section we’ll apply these ideas to a messy enrollment example and walk through the concrete migration steps—queries, backfills, and constraint additions—so you can see a safe, repeatable path from duplication to a maintainable 3NF schema.

Normalization walkthrough example

Building on the concepts we’ve covered, let’s walk through a concrete transformation so you can see database normalization and the moves to 1NF, 2NF, and 3NF in action on a realistic orders schema. Imagine a high-velocity orders table that teams keep extending with more columns: shipping address fields, repeating item lists, item prices, and supplier info all copied into each order row. That duplication creates update and reporting headaches; our goal is to remove redundancy while preserving safe, testable migrations and predictable query performance.

Start with a simple but problematic schema that you might inherit from a legacy service: a single table that mixes order identity, customer details, and a comma-separated list of items alongside per-item prices. For example:

-- messy source

orders(order_id PK, customer_id, customer_name, customer_address, items_csv, item_prices_csv, created_at)

-- items_csv: 'sku123,sku456'

-- item_prices_csv: '19.99,5.50'

This design violates atomicity and hides functional dependencies, so the first step is a practical 1NF refactor: extract repeating groups into a child table. Create an order_items relation with one row per item per order, preserving quantities and prices as atomic attributes. Backfill using an ETL script or a SQL-based unnest, for example in Postgres:

CREATE TABLE order_items (order_id UUID REFERENCES orders(order_id), sku TEXT, qty INT, price NUMERIC, PRIMARY KEY(order_id, sku));

-- backfill pseudo-query: unnest CSV arrays into rows and insert into order_items

After you’ve normalized the repeating group, inspect composite-key dependencies for 2NF violations. If order_items uses a composite primary key (order_id, sku) but stores sku-related attributes like item_name or manufacturer, those attributes depend only on sku, not on the full composite key. How do you detect partial dependencies? Run aggregation checks such as:

SELECT sku, COUNT(DISTINCT item_name) AS distinct_names

FROM order_items

GROUP BY sku

HAVING COUNT(DISTINCT item_name) > 1;

A stable determinant should return one distinct name per sku. When you surface a partial dependency, extract an items table and reference it by foreign key: items(sku PK, item_name, manufacturer, list_price). Then simplify order_items to only order-scoped attributes (qty, unit_price_override) and a foreign key to items.

With 1NF and 2NF addressed, look for transitive dependencies that 3NF eliminates. A common pattern is item -> supplier -> supplier_address being mirrored into order rows: item determines supplier, supplier determines address, and the order table inherits supplier_address transitively. Detect this by grouping and counting distinct supplier_address per supplier:

SELECT supplier_id, COUNT(DISTINCT supplier_address)

FROM items JOIN suppliers USING (supplier_id)

GROUP BY supplier_id

HAVING COUNT(DISTINCT supplier_address) > 1;

If supplier_address belongs to supplier, move it into a suppliers table and ensure orders or items reference supplier_id rather than copying the address. This centralizes updates and keeps each relation responsible for a single set of functional dependencies.

Finally, make the migration operationally safe: implement backfills in small batches, run dual-write or shadow-write during the cutover window, and introduce foreign keys and unique constraints only after validation completes. Use transactions for idempotent backfills, add monitoring on join latency, and consider materialized views or read projections if normalized joins become a read hotspot. By proceeding incrementally—unnesting repeating groups for 1NF, extracting determinants for 2NF, and removing transitive attributes for 3NF—you minimize blast radius and gain the maintainability and correctness that database normalization is meant to deliver. The next step is a reproducible migration plan that codifies these checks and rollbacks so teams can execute the cutover with confidence.